By now in San Francisco Ballet’s season, we’re well justified to call it Artistic Director Helgi Tomasson’s victory lap as he prepares to say farewell at its end, May 9. Programing and performance have revealed how spectacularly he’s succeeded during his 37-year tenure in creating a superb, world-class company. We might also be justified in saying that there’s always room for improvement. Cases in point: The two new ballets created by Christopher Wheeldon and Dwight Rhoden, highlighting Program Six, which had their world premieres Wednesday night.

Each ballet came perilously close to excellence. Each was strong in capitalizing on its creator’s superpowers. And neither quite hit the bullseye.

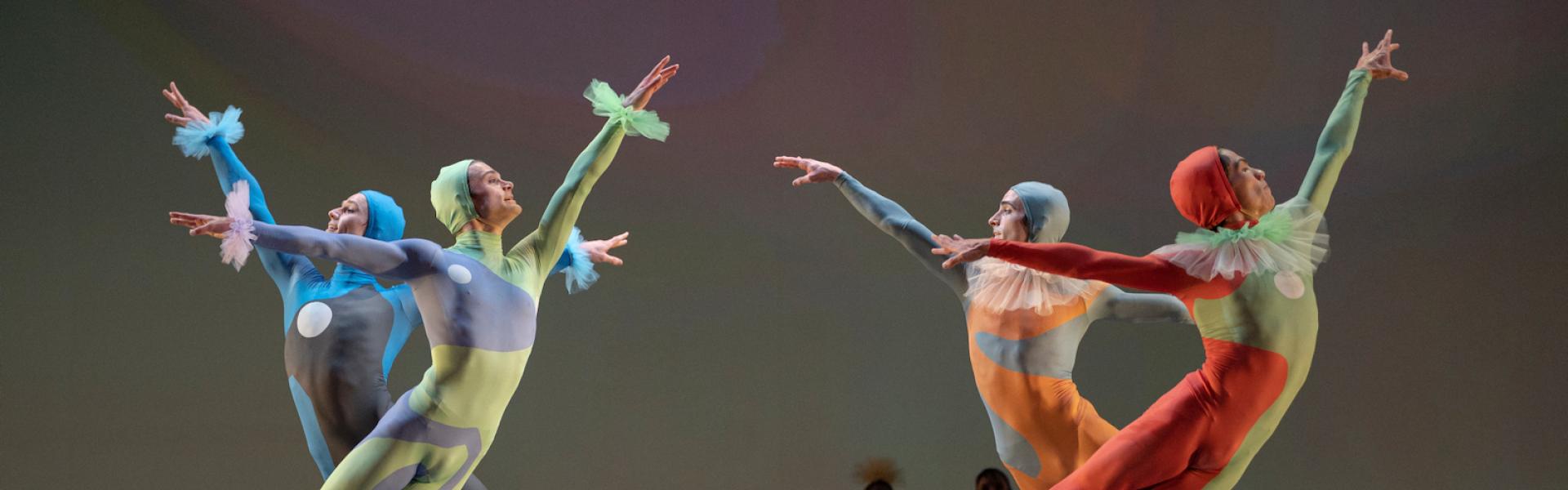

Wheeldon’s Finale Finale, a genial circus of a piece set to a score by Darius Milhaud called Le Bœuf sur le toit (The ox on the roof) was for seven dancers — Dores André and Joseph Walsh; Isabella DeVivo and Benjamin Freemantle; Elizabeth Powell, Cavan Conley, and Esteban Hernandez — all in brightly patterned unitards. Initially created, but not used, for a Charlie Chaplin film, Milhaud’s Latin-infused composition became the libretto for a 1920 Jean Cocteau ballet.

Eleven of Wheeldon’s ballets have been set on the company. What’s lovely about Wheeldon’s new one, a tribute to Tomasson, is how densely it evokes not only Cocteau’s playful theatricality and flashes of something deeper, but also its touches of Chaplin shtick, his waddling walk with the twirling cane, his timing; even — though not via makeup — his arching eyebrows. And — as danced in those beautiful unitards, designed by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung — the somersaulting acrobatic evocation of the Trois Gymnopedies section of Frederick Ashton’s ballet Monotones. And in its circling, rocking moves, the horses of Wheeldon’s stunning Carousel, set to Richard Rodgers’s Broadway musical, created in 2002 for the New York City Ballet.

It feels nigh-churlish not to have been overwhelmed by Finale Finale’s daring, humor, and grace, delivered so beautifully by its septet, but its innate lyricism needed more of an arc, and despite those rising and falling painted ponies, even more of a lift.

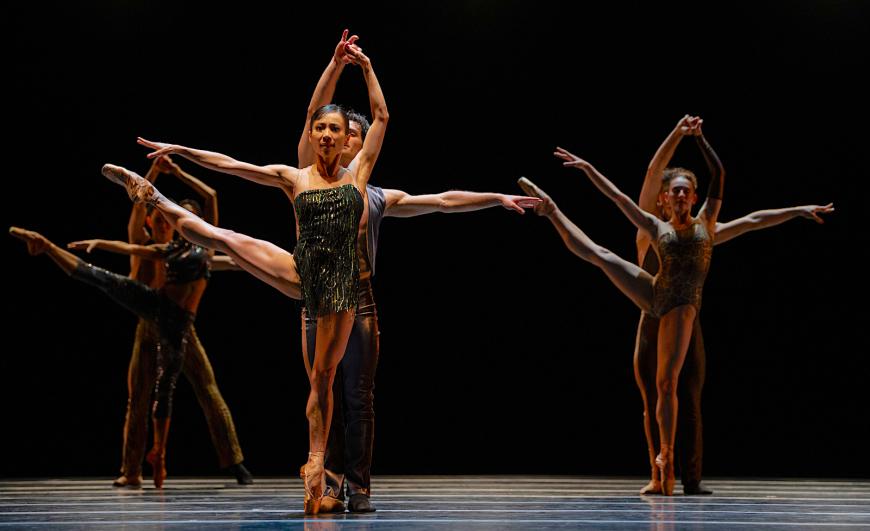

Choreographer Dwight Rhoden says The Promised Land has “a wandering narrative,” and he isn’t kidding. Despite the varied astonishments conveyed by the large cast, as well as a well-chosen array of contemporary composers, it’s a tough ballet to pin down.

To watch The Promised Land just for its beauty and energy would seem to this viewer to give it short shrift, for Rhoden attributes to it allusions to powerful themes; the nation’s emergence from the COVID pandemic as well as its ongoing racial reckoning. And yet there is no ongoing thread to suggest either one. It feels extravagantly vigorous and occasionally poignant. It includes what feels like a false ending, as the cast aligns itself vertically at center stage, the dancers facing in alternate directions. The audience cheered and the houselights rose slightly (or maybe it was a miscue). Then the stage darkened, the line of dancers dispersed, the stage lights came up again and the dance continued.

Perhaps it means, “We as a nation conquered one problem, but then there was this other one.” At any event, we get to see some fantastic performances from nine headliners, beginning with a soloing Esteban Hernandez, who wears spangly pants and leaps like nobody’s business; from Angelo Greco and Frances Chung, close-partnered in sinuous trust, her legs rising and falling like knives, and later, his legs soaring through a freewheeling yet perfect circle of jetés. We can delight as well in the supple, expressive WanTing Zhao and Benjamin Freemantle, in Isabella DeVivo and Joseph Walsh and the stunning perfection of Sasha De Sola and Wei Wang.

Frankly, I felt less concerned about the obscured meaning or messages of The Promised Land. They were in there, somewhere, but there was a huge amount to glory in during that mental search for significance. Let it be noted here that Music Director Martin West and the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra outdid itself here and throughout the evening, as did the remarkable cello soloist, Eric Sung, in The Promised Land.

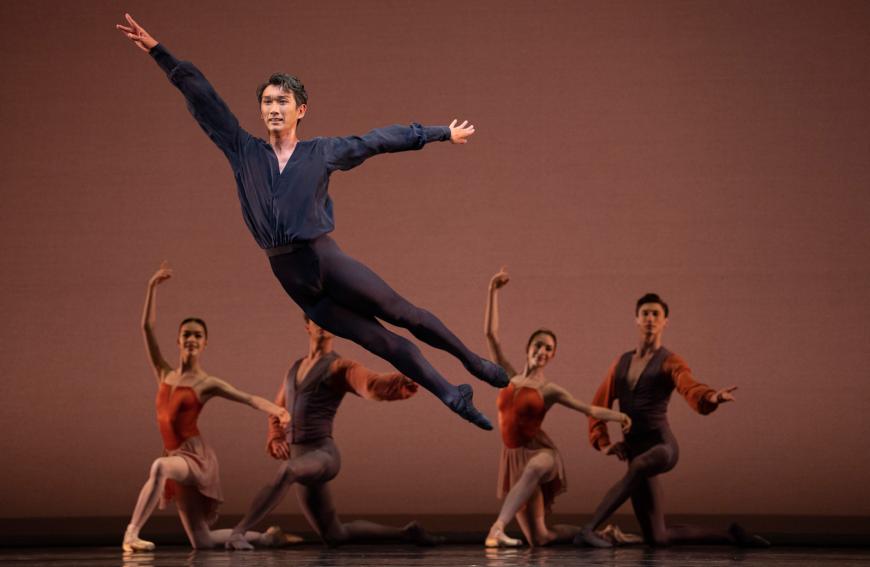

For thoroughgoing fulfillment, though, the program’s opening ballet was the winner. And, fittingly, it was Tomasson’s Prism. It premiered on the Opera House stage in 2000, and has bloomed and grown, edelweiss-like, over the years. Set to the Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 — played by Roy Bogas, now making his final appearances with the company — it remains one of Tomasson’s very best creations. Yuan Yuan Tan, partnered by Tiit Helimets, was exquisite in their soulful pas de deux; the high-flying interludes by Max Cauthorn, Lonnie Weeks, and Julian MacKay, who also had a marvelous pyrotechnic solo, delighted the eye, and Sasha De Sola simply charged and floated through the demanding first movement.

NB: As originally published, this article misstated the name of the solo cellist in The Promised Land. He was Eric Sung, not Paul Montgomery. We regret the error.