With Zakir Hussain making the music and Alonzo King making the dance, the season-launching LINES Ballet show at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts promised to be a good one. Yet the notion of an hour of excerpts, reprised from the duo’s greatest collaborative hits, gave pause. Nothing new? No premieres? And why so short?

Any apprehensions were swept aside the moment the show rolled out at the Blue Shield of California Theater. We’re talking about 60 awe-inspiring minutes, culled from King’s ballets Sutra, Rasa, and Who Dressed You Like a Foreigner? with accompaniment by Hussain, a master composer and musician playing his own work. This would seem to be one of the best outcomes from the pandemic times (See what I did here? The scourge is not over, but it already has its own epoch.), when the troupe wasn’t performing very much and the great works were simply waiting it out while the company’s great dancers, like dancers everywhere, were trying to stay ready and to continue to grow as artists.

There are a few things to consider about an anthology like this one. For one, it does seem to be a highlight reel, in the sense that what’s good and great slides seamlessly into another example of “g and g,” only of a different coloration in mood or style or both. There were also instances of one spectacularly energetic passage knocking right up against another one, which can be a tiresome exercise in too much, too fast — but here, it never seemed to be so. Maybe that’s a function of an audience finally able to stretch toward art, as much as these dancers, having been deprived for so long of a proper outing, an opportunity to move full out, to take chances on a stage, to be welcomed, to be adored.

The lights rose on LINES co-founder and designer Robert Rosenwasser’s rocky backdrop that looked as if constituted of artfully creased gray cardboard. It was surmounted on the left side by Hussain and his kit, which included tablas, bells, recorders, electronic audio devices, and instruments specific to Carnatic Indian music. I was intrigued by the sound of the device that, as it whirled over the musician’s head, seemed to have wind blowing into it and then out of it; it looked like a nylon stocking and sounded like a didgeridoo. And there were bells that burbled, creek-like. How does that happen? It was all a wonderful mystery. Hussain’s artistic output, his percussive symphony throughout, seemed a benevolent message from on high, perched as he was above the dancers. The music seemed utterly fitting to every step below, organically sensible and sensitive, never too loud or too soft.

Adji Cissoko — she of the endless extensions, perfect aplomb, perfect balances, and turns on point — opened the proceedings and was soon joined by two rolling bundles of interlocked dancers who then opened up and, with the addition of others, totaled 13.

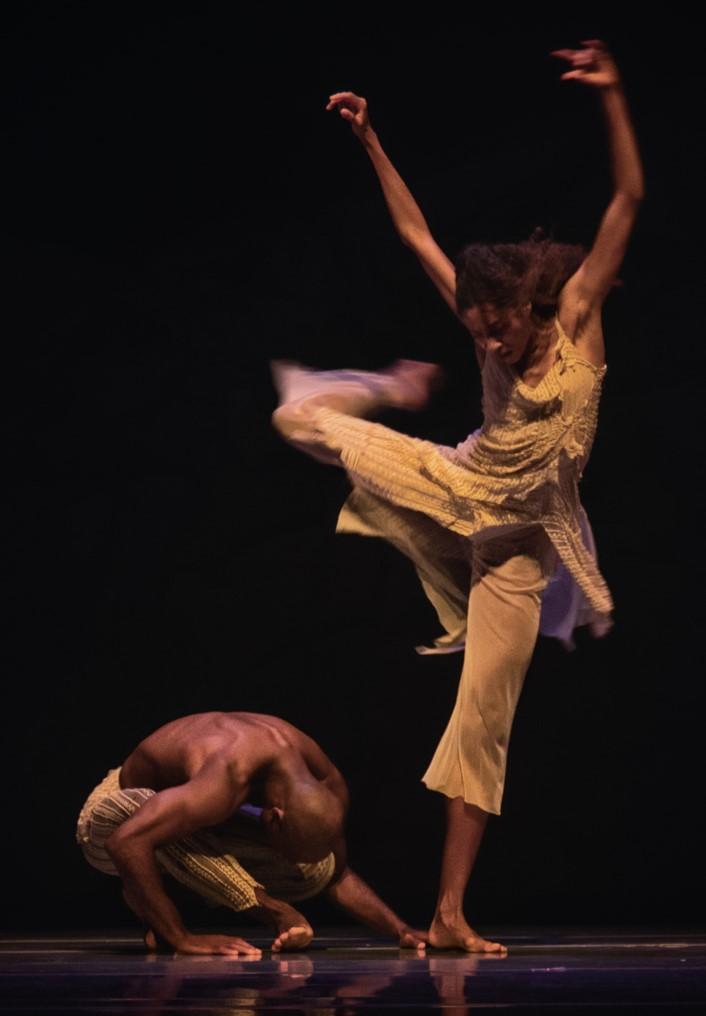

They formed a centipede, arms and legs propelling playfully, which then arrayed into wonderful jogging moves, lunges breaking into huge jetés. There was fabric play; a tall fellow marched by in a stretchy suit that made him look like Gumby by way of Mummenschanz. A dust devil whirled gorgeously onto the stage, lit by Alex Morgenthaler; he was wrapped in sunshine-colored gauzy fabrics, the ochre, yellow, and orange ultimately scattering on the floor. The company took them up, swooped and hid and revealed and made them part of their movement. Probably this was from Who Dressed You Like a Foreigner? Dressed by Rosenwasser and assistant co-designer Sandra Woodall.

If you’re thinking the program was short on description, you’re right. What new connective tissue was there, if any existed among the excerpts, is known only to the company and seemed of little consequence. But the dancers need recognition, and attention must be paid: Cisokko, Babatunji Johnson, Madeline DeVries, Theo Duff-Grant, Lorris Eichinger, Shuaib Elhassan, Joshua Francique, James Gowan, Ilaria Guerra, Maya Harr, Marusya Madubuko, Michael Montgomery, and Tatum Quiñónez.

There was much, much more in the hour, with soloists and platoons arriving, amazing, and departing in unbroken grace, King’s unique voice underpinned by the dancers’ superb grounding in classical ballet and modern dance vocabulary. At about the 50-minute mark, one wondered how long they could sustain that output, that bespoke energy. And that was when there was a stunningly quiet and eloquent pas de deux, with the lineaments of a story. It seemed to speak of love and its pleasures and discontents; it was subtle, it was compelling, and it came to a sweet embrace, a quiet, gentle resolution.

Onstage, it began to snow. The lights went out. When they came back on, the dancers took their bows to a standing ovation. The dancers smiled, the dancers grinned, Hussain came down from his perch, King walked on, the audience roared, and for the cool kids in black who filled the black box theater Sunday afternoon, it seemed like the place to be. And who could disagree with that?