Jewels, George Balanchine’s immortal 1967 gem of a triptych for his New York City Ballet, entered the repertory of the Miami City Ballet in 1992 and arrived at Cal Performances over the weekend for a knockout visit. Keen observers may recall that Jewels was also a cynosure of San Francisco Ballet’s COVID offerings, a tasty video assemblage of three different productions. What a treat, then, to see the Miami troupe live at Zellerbach Hall on Sunday afternoon, Sept. 25, with the work’s three acts — Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds — sparkling to beat the band or, more accurately, the marvelous Berkeley Symphony.

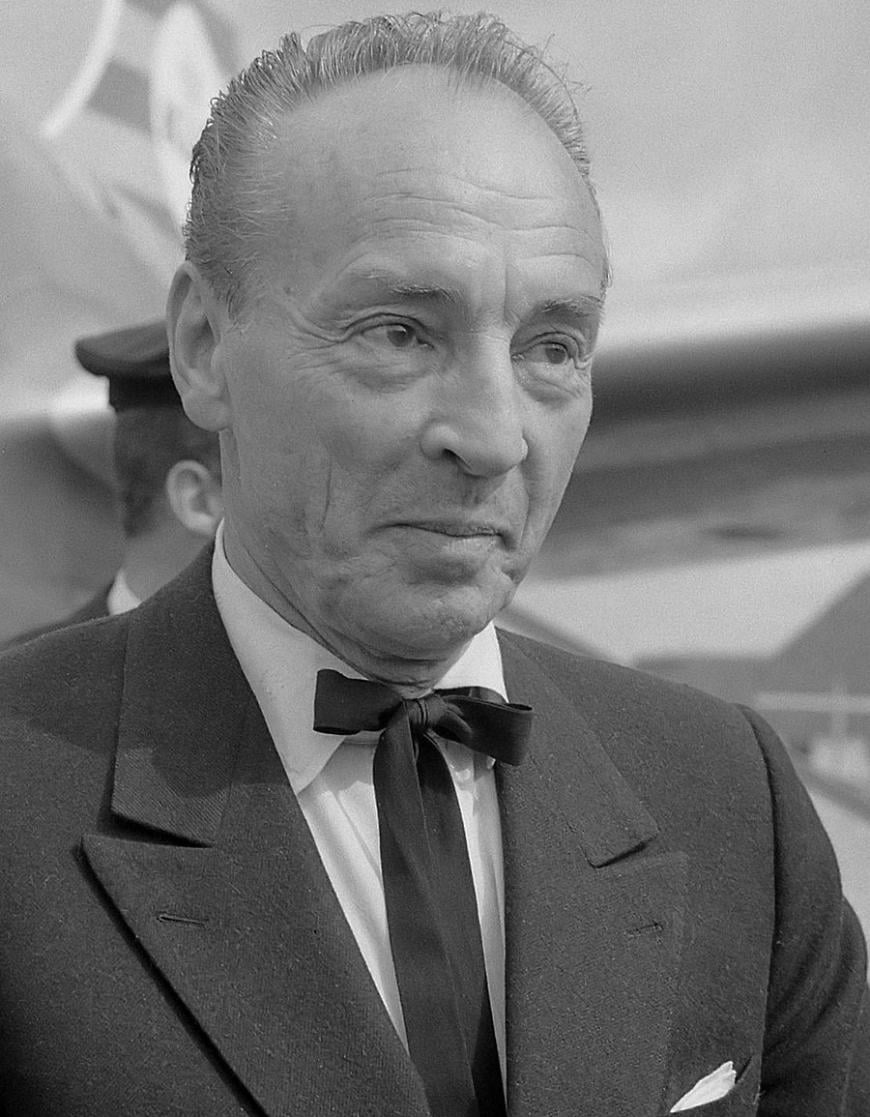

The more time one spends with Jewels, the more stories and lore unfurl. Not hard to do — just search on YouTube for the Balanchine Foundation’s performance and interview videos. If you’ve spent time watching the artists who danced for Balanchine, even better — they’re all there, from Merrill Ashley and Jacques d’Amboise to Edward Villella (Miami City Ballet’s founding artistic director) and Patricia McBride, among many others. The foundation holds its repertory, dancers, and their memories close, sharing, preserving, and extending the choreographer’s genius, a gift for dancegoers of every era. It’s always so entertaining to remember Balanchine’s cynical quote about his creations and his company’s artistry dying with him — “après moi, le board” — and to know, nearly 40 years on, that he knew he was pulling everyone’s leg.

We’re lucky enough to have had Helgi Tomasson, formerly of New York City Ballet, running SF Ballet for 39 years. And in Miami, there’s former NYCB principal dancer Lourdes Lopez, who danced for Balanchine and his successors for some 25 years and took over from Villella in 2012. Board, shmoard — there’s no stultification here, only growth, interrupted but unbroken by COVID, still superintended by a team with strong NYCB links, as well as expansive ties to Miami’s Latin American community and artistry.

On with the show. The curtain rose on a spring garden of ballerinas and their partners in green, the designs those of the legendary NYCB costumer Barbara Karinska; Tony Walton’s backdrops, beginning here with green sparkles on a black ground, were the perfect frame. Emeralds amply fulfills its obligations to beguile the audience into an entire evening of opulence. But we cannot live by jewels alone. Balanchine crafted supple ports de bras, perfect and eloquent arm work, and — thanks to Gabriel Fauré’s Pelleas et Melisande — a waltzed invitation to the dance, pointe shoes whispering seductively, gentlemen beautifully supporting and lifting their partners. An understated atmosphere of ease, beauty, and precision leads to moving tableaux of remarkable magnetism. Emeralds ends with a passing well-deserved tribute to the male soloists, massing them onstage, but we are never in doubt that the dance is really about the women, and they were marvelous.

Rubies, the central ballet, had a stunning outing Sunday, with Jennifer Lauren, Alexander Peters, and Jordan-Elizabeth Long leading the way. From lobby talk, it’s quite clear that this is the most popular bauble of Jewels — rubies on rocket fuel. It’s crazily clever, and it never stops, never runs out of ideas. The powerfully supple, endlessly morphing Long, in one of Balanchine’s legendary “big girl” roles, punctuates the festivities. She projects beauty, independence, and a certain sly alertness. She is, yes, a fox.

As the charmed couple, grinning from ear to ear, Lauren and Peters interact with complexity, separate with alacrity, and seem to be having an amazing time of it. Peters, his red hair a gloriously blazing topper to his costume, never flagged. If you run forward, soon you’ll run backward; if you run backward, soon you’ll be vaulting skyward, or perhaps accelerating through a series of chaine turns, faster and faster into the wings. Lauren’s demanding pointe work and manèges of spins came through without a hitch; she had the added task of being drawn to her partner and yet drawing back from him. She seems to be sure of what she’s doing, but she’s pulling back, keeping him on his toes — as if he weren’t already. All of this would be useless without the corps’ unflinching energy, precision, and high spirits. Like Igor Stravinsky’s music here, Rubies sang.

As for Miami’s Diamonds, it gave this onlooker a new perspective. Sometimes, in less attentive performances, it seems a pleasantly dutiful evocation of Tchaikovsky’s greatest ballet hits, all in white, a little vaguely this one or that one. Not here. Throughout, it felt fresh, alive, inventive, evoking new vistas for old glories. Full credit here to the principal couple, Dawn Atkins and Steven Loch, who devoured their anointed roles of a queen/swan/maiden and king/prince/suitor, projecting a steady charm and ease. Atkins has great poise, aplomb, marvelous extensions, and an unexpected durability beneath all that grace. Loch is one of this role’s most attentive partners and strongest pyrotechnicians, with grand pirouettes for days; the duo draws substantial support from each other as well as from the eight soloists and the huge and beautifully unified corps de ballet. Let’s pause here to note the delicate beauty of the headdresses, embracing swan-ness and regalness (and wait, is that a butterfly on the top?) and also Walton’s set, where the sparkling diamonds array against the backdrop as a chandelier, which then, climactically, lead to an entire litter of baby chandeliers. A diamond is forever — no kidding.

Jewels was midwifed by Van Cleef & Arpels, the New York jewelers who rivaled Tiffany back in the day and helped underwrite Balanchine’s new ballet, which spurred quotes from the master about Georgia’s gems and Paris’s perfumes and the underlying aromas of mystery and romance that accompanied such treasures.

But it’s also been said that the three sections refer to different periods in Balanchine’s life: Emeralds, set to Fauré, to his time in Paris, where his little chamber troupe fled the post-czarist upheavals and hardships of the Russian Revolution and eventually joined Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes; Rubies, set to Stravinsky, like Balanchine a Russian-American emigre, recalling, with its aura of “Times Square at midnight on New Year’s Eve,” said Balanchine, a world of leggy showgirls and nonstop hustle. Then finally, splendidly, Diamonds, set to Tchaikovsky, with its unbridled classicism, passionate romanticism, and glittering magnificence, was Balanchine’s lifeblood. Once you see it, maybe it will be yours, too. Every heart has its reasons.