We could get away without a review of the San Francisco Ballet’s video of George Balanchine’s Jewels, the next offering of the company’s virtual 2021 season, available on video through April 21. It’s not new, although its Emeralds section has been newly recorded via video capture. It premiered in 1967 at the New York City Ballet and has been in the SF Ballet repertoire since 2002.

But, and this is important: It’s also a great ballet. We’re at a liminal moment, when some things are beginning to reopen (we just heard of an probable date — June 15 for California!) while other things, like the San Francisco Ballet’s next live season at the War Memorial Opera House, are at some indefinite distance down the road.

So this review is offered for your consideration. Jewels is a tantalizing exemplar of what lies ahead when live performances return not only to the Opera House, but everywhere.

Jewels on video embodies why we sit in theaters in the dark. As danced, it’s thoroughly virtuosic. As a ballet, it’s exquisite, as might be expected from a work whose three sections are titled Emeralds (music by Fauré), Rubies (Stravinsky) and Diamonds (Tchaikovsky). It’s romantic. It’s charming. It’s frisky. It’s majestic. Hang on just a little longer, says Jewels. Help is on the way.

Although Jewels has a reputation of being the first abstract ballet, which just shows you how unreliable reputations can be, it’s neither the first nor is it really abstract. Like many other ballets, it has no plot. In fact, it’s really three ballets that have no plot. But each evokes, well, stories, images, memories. It’s up to you — choose your own adventure. Balanchine said, “There are no mother-in-laws in ballet.” In other words, if you simply put a man and a woman on the stage together, you have a story.

The story of Jewels began with Balanchine’s friend the great violinist Nathan Milstein, who connected him with the jeweler Claude Arpels, as in Van Cleef and Arpels, which inspired him to create a ballet with jeweled costumes. As a Georgian, from the Caucasus Mountains region, Balanchine said, he was always attracted to gemstones. He thought about using sapphires, with Schoenberg in mind, but “the color of sapphires is hard to get across onstage,” he wrote in 101 Stories of the Great Ballets, co-authored with Francis Mason.

With costumes designed by the legendary Karinska, the jewels were and are synthetic — real ones would be way too heavy. So when the curtains open on Emeralds, we see a glittery emerald brooch, suspended like a chandelier above the stage.

Misa Kuranaga embodies warmth and graciousness, arching pliantly backward through lifts with her partner Angelo Greco, who joins the eight corps women in forming filigreed chains, arms subtly interlacing, creating a kaleidoscopic succession of different patterns, like cats’ cradles.

The second principal couple, Sasha Mukhamedov and Aaron Robison, adds a more playful mood, with expansive turns, grandes battements, and developpes. There’s a pas de trois, followed by a quiet pas de deux. There’s no story here, says Balanchine, but then he adds that Emeralds is “perhaps an evocation of France, the France of elegance, comfort, dress, perfume.” Thanks! I can take it from there.

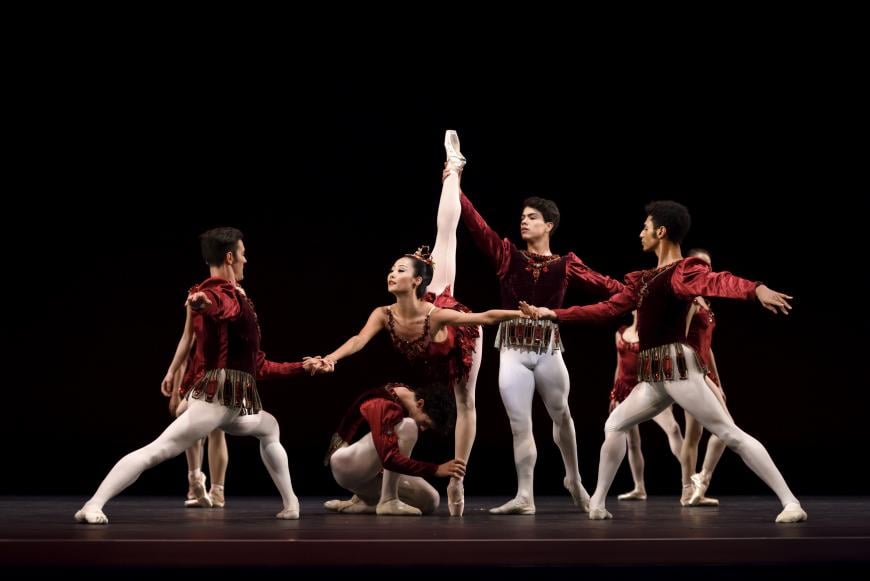

Rubies, the central ballet, is the best-known of the three, by dint of both the stunning ruby-red satin costumes, bejeweled, of course, with ruby stones, as well as Balanchine’s remarkably zestful invention, a match for Stravinsky’s. Its delights begin with the corps’ playful setting for the first pas de deux, an introduction that includes little circling turns on the heels of their toe shoes. Pretty soon, we see Mathilde Froustey and her partner, Pascal Molat. How delicious is their dance? Well, Froustey’s elegant moves are like the richest cream. Her legs rise smoothly into perfect passes and arabesques, gentle and unhurried for all their speed. It’s pure sorcery.

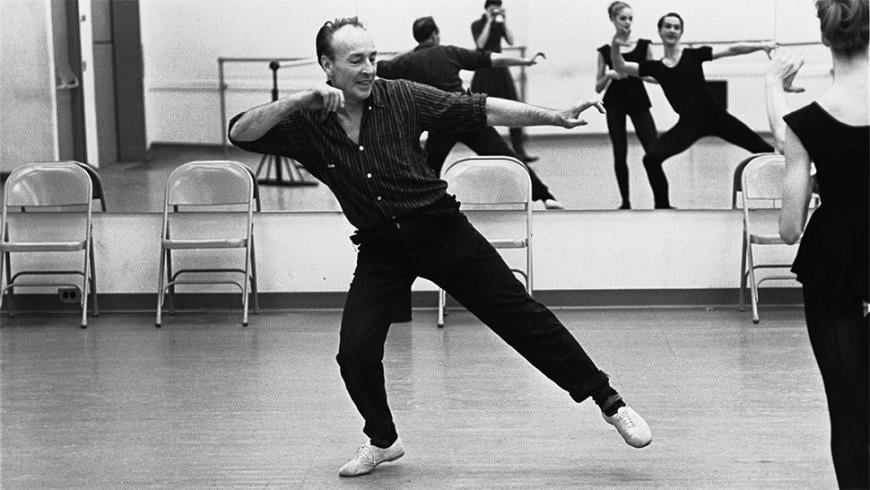

Molat, like Froustey a Paris Opera Ballet alumnus, is a do-it-all dervish. He partners like a god (a naughty and flirtatious one), but he’s at least 50 percent jester — and incidentally, Rubies often evokes the red suits in a card deck — they’re elegant and remote, yet holding the chance of fortune and merriment. Molat, who gave up soccer for ballet, kicks it up several notches, spinning and sprinting at breathtaking velocity into the wings. Since this video was made in early 2016, Molat has entered an active retirement of teaching and performing. Watching him, it’s impossible not to want him back.

Diamonds, captured on video in 2017, is climactic in every sense, from the twinkling shimmer of its chandeliers, the sinus-clearing white of its bling-trimmed costumes, and its diamantine tiaras, rising like fountains even before the corps de ballet gets on pointe. When they do, they exude precision, the sheer bounce and joy of swift movement and waves and waves of charm, juxtaposed with all that grandeur.

Once again without a story, Balanchine captures everything we need to know about royalty, dynasty, courtliness, fealty, and love. And loss. And, of course, love regained, and the grandest of processions a la polonaise, the members of the court reaching back, Marie Antoinette style, to their humble roots.

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 3 in D Major, excerpted here, includes two Scherzos, a slow movement and that polonaise. The music evokes Petipa’s choreography at peak eloquence — stirring memories of Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, Paquita, Raymonda, all inspirations to Balanchine, who grew up in the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg. We’re on a trip to Russia via the New York State Theater, where, not coincidentally, San Francisco Ballet artistic director Helgi Tomasson danced for Balanchine.

Sasha de Sola and Tiit Helimets glittering perfection, capture all the sparkle with virtuosic skill tempered by warmth. De Sola has bravura technique, effortless extensions, exquisite balance, airy buoyancy. Helimets, here at his peak in easy elevations, embodies strength and grace. Their dancing honors choreography that might embrace a dancer’s dream — capturing every eyeball in the house. There are 36 dancers in the corps, and the finale’s grace and sweep fills the stage as we, willing captives to our screens, envision a return to the past.