Back-to-back shows of six brand-new ballets during San Francisco Ballet’s “next@90” festival last Saturday at the War Memorial Opera House offered a rousing assortment of promises, surprises, brilliance, and trouble, making it impossible to look away. The six — three at the matinee, three at night — were without fail beautifully danced by the company, yet another feather in its post-pandemic cap. The works were chosen by Helgi Tomasson, somewhat extending his 37-year reign as artistic director (and we’re glad), and rehearsed with input from Tamara Rojo, his successor as of 2023.

With three more ballets yet to be seen, a quick-and-dirty assessment shows the score at two for six in terms of perfection. That’s a terrific achievement; the other four had peaks and valleys, with the high points more memorable than the low. The festival officially ends this week (Feb. 11), but individual ballets will be presented in repertory seasons to come. Each, as well as the artists who created and perform them, is worth your attention.

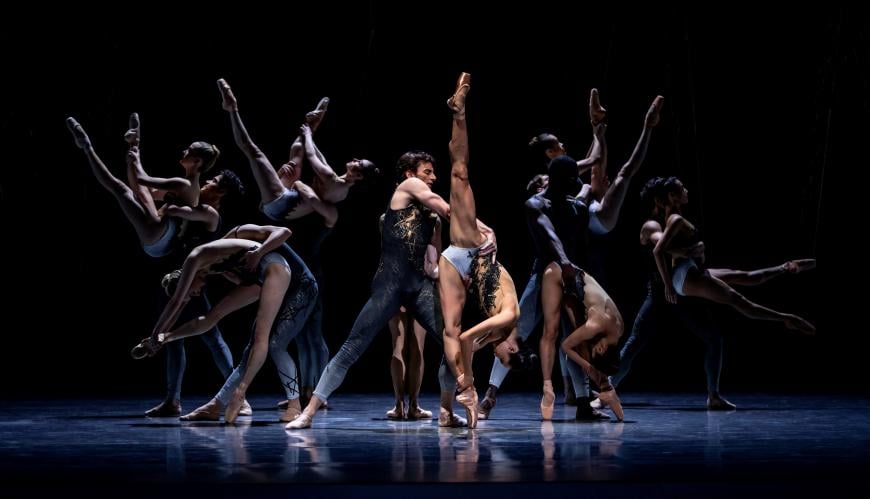

The matinee began with Kin, choreographed by Claudia Schreier, set to music by Tanner Porter. The ballet’s theme is the domination of one woman (Dores André, partnered by Isaac Hernandez) over another (WanTing Zhao, partnered by Aaron Robison), the domineering figure switching back and forth amid a corps of six ballerinas supported by their partners in a multitude of grand battements and stunning penchés. It appears that the Harvard-degreed Schreier, thoroughly schooled in ballet and passionately involved with it, has never danced in a professional ballet company, although she has received multiple prestigious commissions and awards in the field, an accomplishment rarely encountered. The idea of a rapidly shifting relationship is certainly more familiar, and most intriguing. But the puzzle in this instance is why it shifts back and forth. Lacking that knowledge gives the ballet a static quality despite all its surface exposure.

SF Ballet alumnus Nicolas Blanc’s Gateway to the Sun, set to music by a go-to dance composer, Anna Clyne, is based on the 13th-century Rumi poem “Dance.” The musings of the poet (Max Cauthorn) are set against a windswept desertscape, its set and costumes by Katrin Schnabl, its steadily shifting moods enhanced by Jim French’s lighting. There are 13 dancers, all of them expressions of the poet’s varied musings. It’s a pleasingly adventurous, open-gendered ballet, finding well-articulated expression in its variegated poses and positions, acrobatic lifts, and daring falls.

Resident choreographer Yuri Possokhov’s Violin Concerto is set to the Igor Stravinsky Concerto in D for violin and orchestra. The music is in Possokhov’s muscle memory, and why wouldn’t it be? As part of SF Ballet’s George Balanchine repertory, it was among Possokhov’s dances. Feeling he had something more to say about this audience favorite, he choreographed it for seven couples.

It’s smashing, a success on the order of Possokhov’s crowd-pleasing Magrittomania. Buoyant and securely so, it goes forth beneath blown-up black-and-white backdrop photos of Stravinsky and his music scores, looking on solemnly yet attentively through his trademark black spectacles. A flirty Muse (Juliana Bellissimo) in a frothy pink tutu leads the way for three principal and four ensemble couples, and Cordula Merks is the solo violinist. Your correspondent was too busy enjoying Violin Concerto’s wit, musicality, energy, and daring — think of it, taking on Balanchine AND Stravinsky at one go, and winning! — to take notes. Go see it.

Another great ballet arising from “next@90” is choreographer Robert Garland’s first piece for the company. Garland, capping his years at Dance Theatre of Harlem by succeeding Virginia Johnson as its new artistic director, works here with Mozart for his own Haffner Serenade. DTH founder Arthur Mitchell also choreographed a ballet to the same music, but this one’s completely different. Garland, we’re told, used to choreograph Soul Train dances in the living room with his sisters. And Garland says, “Don’t be afraid to understand that the rhythm of Mozart isn’t any different than the rhythm of hip-hop.” Hard to believe, until you see the new ballet.

Frisky and adorable is an understatement. Against a bare stage, here comes Cavan Conley in a pink onesie, as a neighbor described it Saturday night (costumes by Pamela Cummings), leaping in circles, feinting with his fetching partner in green (Julia Rowe), setting up those beats, those wonderful “gotcha” accents, boppy and wiggly, taken up by the other four couples. A charming low-key formality ensues, giving way to a passage that suggests that a very young man is trying out moves that he hopes will please his partner. Which they do, leading to passages that are mischievous, which move onward to a gently limpid break, followed by Conley’s marvelous fusillade of grand pirouettes and air turns. Life is like that, especially life after such a challenging time for dancers and the people who watch them, making Haffner Serenade another must-see.

Jamar Roberts’s Resurrection, set to Gustav Mahler, is a disappointment from the gifted former Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater resident choreographer, whose 2016 Members Don’t Get Weary was a triumph of the company’s West Coast visit. Resurrection’s story, of an evil queen set on seduction and subjugation of a man who can help her oppressively rule her kingdom, is strongly modern in flavor, down to the absence of pointe shoes, but the problem seems to be more in the direction of a confusing narrative rather than any shortcomings of artistry or intent. Among the standout performances were Norika Matsuyama and Luke Ingham as the unhappy couple.

Danielle Rowe’s Madcap, whose star, the clown, is played by the wonderful character dancer Tiit Helimets, is perhaps two theater pieces. The first is a festival of circus archetypes. Rowe, who also choreographed 2021’s Wooden Dimes, excels at capturing the essence of characters. The second aspect of the ballet is its choreography, which goes more, it seems, toward capturing gestures that reinforce the archetypes than the dynamics of dance. That emphasis and reiteration as the figures come to life seem to slow the narrative and the kinetic impulses that work toward building movement that leads to dance. The characters, these circus denizens, are marvels of synchronicity at the expense of breakout movement. It squashes something vital in the story. Poor clown, a complex and haunting figure of stillness and sorrow, literally rarely gets off the ground. We can’t tell if he has the potential to be happy or sad; he seems more soporific than anything else. Pär Hagström composed the songs, which were arranged by Philip Feeney. Emma Kingsbury did the miraculous costumes, and the lighting was by Jim French.

Festival conductors of the SF Ballet Orchestra included Music Director Martin West, Matthew Rowe, and Ming Luke.

Corrections: The article as originally published included the wrong end date for the “next@90” festival. It also said Helgi Tomasson had choreographed a ballet to Mozart’s “Haffner” Serenade; rather, it was the composer’s “Haffner” Symphony. Lastly, Jamar Roberts was identified as Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s resident choreographer; he was formerly in that position.