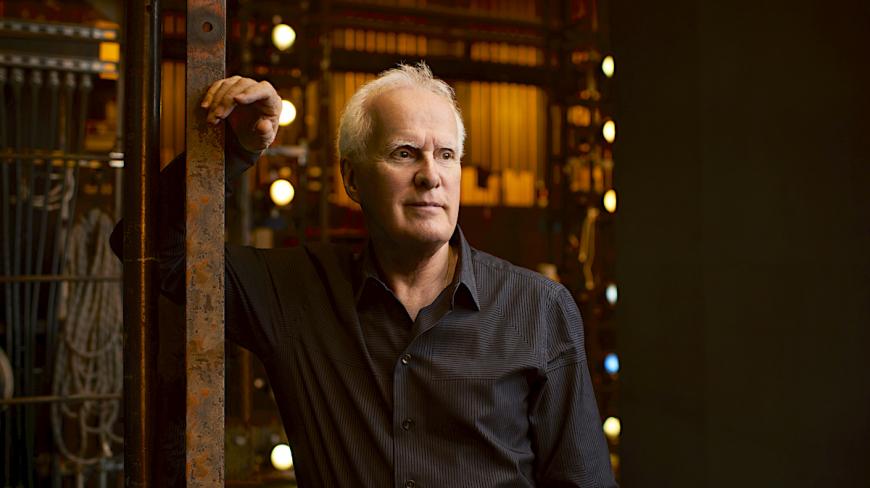

Helgi Tomasson isn’t what you might call a confetti kind of guy. And yet there he was Sunday night, front and center on the War Memorial Opera House stage after the gala performance, surrounded by his dancers, staff, his family, and a panoply of ballet big names. Tomasson looked both delighted and teary as his 37-year reign as artistic director of the San Francisco Ballet came to a close, and the white stuff came showering down as the audience stood up and cheered.

It was, perhaps, Tomasson’s very nonconfettiness, his lack of frou-frou and pretense, that brought him to this moment: All those years of grinding it out on behalf of his art form, his artists, interspersed with moments of worry, joy and sheer genius, combined with a sense of adventure in finding and developing fine choreographers, helped move America’s oldest ballet company into the world-class category. “You danced beautifully tonight,” he said, thanking his dancers.

Even on this triumphal night, dubbed “Helgi Tomasson: A Celebration,” his words were pure Helgi. The “one person” responsible for his success, he said, brushing away a tear, was his wife, Marlene. After they embraced, he said she understood his work because she, too, had been a dancer; they’d met in the Joffrey Ballet.

“I treasure that the company is improving in a very good period, he said, which made him “sad” to be leaving, but “nothing is forever.” Saying he’d been blessed with great dance makers and dancers, he added that his motto throughout his tenure has been, “Change nothing, gain nothing.” There was more, but in keeping with Tomasson’s classically modest sign-off — “I think that’s enough out of me now,” we can turn to the show.

It was certainly one of the best celebrations SF Ballet has thrown for itself. It had as much to do with the programming as with the pieces themselves. The evening had a chamber intimacy. The house seemed full of seasoned dancegoers, identifiable by their lack of clatter and the warmth of their responses.

Unusually, instead of the normal gala previewing upcoming premieres, with some full-company appearances, this collection of excerpts, plus the longer Harmony, set to a Rameau suite, were all choreographed by Tomasson, and each piece felt complete in and of itself, a tribute to his craft. All were a chance to really focus on and admire the dancers’ individual gifts and qualities. All had a certain lapidary charm, further burnished by the dancers’ flawless, often thrilling performances.

Following a film tribute, Chaconne for Piano and Two Dancers, set to Handel, put Frances Chung and Wei Wang in grey tights, a low-key opener for a gala — until they moved in their two pools of light, then launched their pas de deux with small bourrées and Chung’s midair gargouillades as Wang raised her up. Then in what Twyla Tharp once described to me as “he goes then she goes,” they in turn delivered supple, melting bends, soaring jetés, perfect spinning turns and, from Wang, perfect backward bourrées, a step that, when going forward, is mainly the province of the ballerina; here, it looked groovily adventurous. The frequent independence of each dancer, their speed and precision, and the context of the music owed much to the Bournonville style, part of Tomasson’s schooling in Denmark. Roy Bogas was the pianist.

Two Bits (1998), set to contemporary composer Aaron Jay Kernis, a pas de deux with a flamenco accent set to strings that included a guitar, was wildly flirtatious; often, the object of the flirtation was offstage, presumably recovering for the next exuberant passage. It was enchanting, offering Isabella DeVivo and Esteban Hernandez chances to be a Carmen and a toreador, equally (and refreshingly) seductively; to dive backward, embrace passionately, step boldly, legs like swords, and smolder in mere seconds of repose. The musicians were David Tanenbaum, guitar; Cordula Merks and Ani Bukujian, violins; Yi Zhou, viola, and Eric Sung, cello.

The same musicians played Concerto Grosso (2003), set to Francesco Geminiani after Corelli, for five dancers, keynoted by Lucas Erni, an acrobatic fireball in a red unitard, leading four more virtuosi clad in various hues. Of note was the partnering of man quasi-lifting man from the wings toward the center, still a relative rarity. To a panoply of soaring, leaping into grand plie, and holding slow turns in attitude, was added an interesting gesture, a sort of “who, me?” twitch of the head following one perfect landing or another.

Yuan Yuan Tan, who has danced for Tomasson longer than anyone else — 27 years — and Tiit Helimets delivered the ravishing pas de deux from The Fifth Season (2006), by composer Karl Jenkins. One of its opening moves puts Tan in the supplest of backbends as she is lifted in her partner’s arms; no mean feat, lovely and audacious. The piece is dotted with traditional, intimate embraces that give way to unusual, fizzy lifts, the duo sparkly in grey costumes by Sandra Woodall, with abstract fog-like panels by Michael Mazzola. Their final pose, as she is lifted by him, then lies across his legs, which are deep in a grand plie a la seconde, is breathtaking.

Sasha De Sola and Joseph Walsh frisk blithely through Elena Kats-Chernin’s ragtime-infused Blue Rose (2006), played by Britton Day, piano, and Cordula Merks, violin. Nothing blue about it. Sunny and perfused with gold, beginning with Julianna Lynn’s dress design, it’s pert and sassy, with toe taps and hip switches that send the pleats swirling, pirouettes and echappes, and for Walsh, nothing less than perfect leaps. The whole thing is capped off by De Sola’s lightning-fast piques in a perfect circle.

Harmony, also set to Rameau, was created at the height of the pandemic in 2020. Part of a project to let dancers create in small groups away from the studio, it became its own thing, its theme and six variations, and also a personal wish for inner peace from the artistic director, who created solos and duets for the dancers, then combined them with choreography for the entire cast when it was possible to return to studio work. It was part of program five this season, and I’m sorry I missed it.

As it opens, 12 dancers slowly emerge from shadows, dancing down designer Jim French’s diagonal ray of light. The shadow and light are part of Tomasson’s masterly deployment of gravitas and playfulness, a commemoration of darkly challenging days past and a bright future to come. Aside from the sweet and tender hopefulness embodied in the supple partnering, there were bright and vigorous interludes, bright pas de chats (catlike leaps), swirling waltz moves that showed off the lovely gowns of festive green, with contrasting bright underskirts, by Emma Kingsbury. There were promenades, slow lovely turns surprised by swoopy lifts. Throughout, there was a sense of slow, then quick, a sensibility underscored by what looked like freeze-frame moves. Elevated charm, a calmer languor, and always a wish for brighter days.

The ensemble dancers were Alexis Ailudi, Carmela Mayo, Diego Cruz, Leili Rackow, Julia Rowe, Cavan Conley, Luca Ferro, and Lleyton Ho. The principal dancers were Wona Park, Max Cauthorn, Misa Kuranaga, and Angelo Greco.

Given the success of “Helgi Tomasson: A Celebration,” is it unrealistic to hope for future anthologies during the repertory season? They could be a way to highlight superb dancing and continue to salute Helgi Tomasson’s work, as well as that of choreographers yet to come.