Yes, I knew Paul Taylor. Yes, we were on a first-name basis. He sent me a nasty missive once, writing in pencil between the lines of a carefully clipped-out New York Newsday review of his Speaking in Tongues, a work I didn’t understand and didn’t like. His critique, quite obscene, nearly burned a hole in my desk. I sent him a chiding letter back. Weeks later, he sent me a card. Two bugs were glued inside (only one survived the post office’s ministrations intact). Each had a speech balloon:

“Nice Paul.”

“Nice Janice.”

Opposite, he’d written, “Dear Janice, Guess what? You and I are friends again. Love, Paul.”

I just wanted to mention that, since a columnist I admire wrote recently that it was self-aggrandizing to emphasize a personal connection to a deceased celebrity. I don’t agree. It’s anecdotal evidence of a great choreographer’s mercurial behavior, and of his wish to protect the dancers he lovingly called his “Golden Gang” — a former art major at Syracuse University, Paul had tinted their photos hanging in his home with auras of gold leaf — from all negative reviews. It’s also a biographical footnote. Paul collected bugs and, before it became an ecological no-no, butterflies. He had a butterfly net that he wielded with professional aplomb in the vibrant meadows around his vacation A-frame, with its view of the sea on Long Island’s North Fork. The trophies were encased as a collage in his glass coffee table in his lower Manhattan townhouse. He sent a stunning monarch butterfly as a wedding present.

But to begin at the beginning. I was a little baby dance critic when I first saw a piece by Paul Taylor. It was 1982 and the troupe was at City Center in Manhattan. The program included Diggity and ended with Esplanade. I’d taken classes in modern dance and had seen a few companies perform. Once in my early teens, I actually saw Martha Graham dancing with her troupe. She had stepped back, but she was still the cynosure. Sturm und drang! Those contractions, those torso tilts! The pliability! Some of the works were made in the 1930s, yet they felt so avant-garde. I don’t think I saw Paul, who said he’d decided to switch from art to dance after seeing a Graham photo book in the university library. He studied at Juilliard, got into Graham’s company in 1952, and, with his strapping grace and innate sensitivity, was one of Graham’s favorite partners.

Paul Taylor ultimately formed his own company, giving his first solo concert in 1957. The last survivor among the modern dance immortals — Graham, Merce Cunningham, Taylor — he prepared several years ago for his eventual demise, designating dancer Michael Novak as the next artistic director, building a repertory chosen from his own works as well as modern dance from other notable companies, and changing the name from the Paul Taylor Dance Company to Paul Taylor American Modern Dance. He died Aug. 29 in a New York hospital of acute renal failure. He was 88.

When, in the late 1970s, I had the good fortune to begin writing about Paul Taylor, he was settling into his deliciously unsettled and unsettling, most brilliant era, having netted one of the best groups of company artists ever. In the 1960s and ’70s (Taylor stopped dancing in 1974, after an injury), his company included future innovators like Twyla Tharp and Pina Bausch.

Paul Taylor’s dances were like no modern works I’d seen before — bright and cheery (but never glib), or darkly glowering, yet inviting, like a Bengal tiger, perhaps, or intricately observant, like Paul Taylor the collector (Insects and Heroes) and people watcher (Lost, Found and Lost, set to “Mantovani elevator music,” said the program).

His subjects were adventurous, even when seemingly mundane. Diggity, for instance, was an obstacle course, a stageful of cutout doggies of every description, standing shin-high in the dancers’ paths for them to skirt narrowly, or jump over, or smile at indulgently. Weird. And yet why not? Graham’s Errand into the Maze had Isamu Noguchi’s twists and turns as challenges set before a grimly determined voyager. Diggity offered different impediments, cuter ones. The goals were to maintain that ineffable Taylor-esque presentation, more everyday movement than dance vocabulary, with a strong, elegantly pliant back, carefree arms, childlike flex-legged jumps, and blithe spirit. So here were frequent design collaborator Alex Katz’s cheerily obstructionist pooches, with their boldly spotted bodies.

This was also the era when Taylor’s classic, Esplanade, drew enormous attention and affection. Long enough to admit multiple moods, and to explore human alienation as well as trust and affection, brilliant in its varied colorations, its famed derring-do as the women dancers buoyantly leaped and twisted and hurled themselves to the floor, over and over again, dashing across the stage and caught by the menfolk at the last minute, held closely and calmed and tenderly walked into the wings. The sublime Baroque music was dead-on. It was chosen by a choreographer who professed indifference to it; all music need be was suitable filler for his dances, he implied with a straight face.

He was a self-assured and iconoclastic fantasist. He liked narrative dances, of which my favorite is “Rite of Spring,” set of course to Stravinsky, an acutely imaginative nightmare that paired a dance company with a film-noir detective storyline, moods and moments shifting with brutal humor and witty brutality.

And he liked to tell stories; read his autobiography, Private Domain, his first book. He liked to explain the unexplainable. Listen to where he said he found music — The Laughing Record, inspiring goofy dance scenarios, on top of a dumpster, the Andrews Sisters’ record that gave rise to his Company B in an alley.

When Paul Taylor danced, everyone said it was impossible to look anywhere else. Even after he’d stopped dancing, at rehearsal, sitting on the sidelines in his studio, he’d demonstrate a gesture, simply stretching one impossibly long, graceful, quietly powerful arm upward, and guests would stop looking at the dancers and focus on the choreographer.

And as he moved, so too he moved with the times. He did masterly antiwar ballets — Sunset in a leafy Katz-designed glade with music by Edward Elgar as red-hatted soldiers flirted with their girls, thought in vignettes — of love and death and how physically close they were to their brothers in khaki, and later the Andrews Sisters medley, with bouncy jitterbugs and death by sniper and dreams of a future world of peace. He dealt sensitively with AIDS, with the sexual revolution, with bouts of his own inner turmoil. He did a fairy tale, Snow White, with a clawed, long-nailed hand, proffering an apple to Snow White. And he adjusted the story to the size of the company, turning the Seven Dwarfs into Some Dwarfs.

He had on hand, besides an essential eloquence, a tender regard for his friends. He also embodied a lot of silliness and wide-eyed little-boy sass. A smoker, Paul sat for an early-morning interview — “How’s 6:15?” he asked — in his garret office in New York, lighting up one cigarette after another. I’d quit 25 years before; at 80-plus, he was still at it. “It’s my house,” he said sternly, then chortled — “and I can do whatever I want.” He did it all, and he did it like no dance maker ever will again.

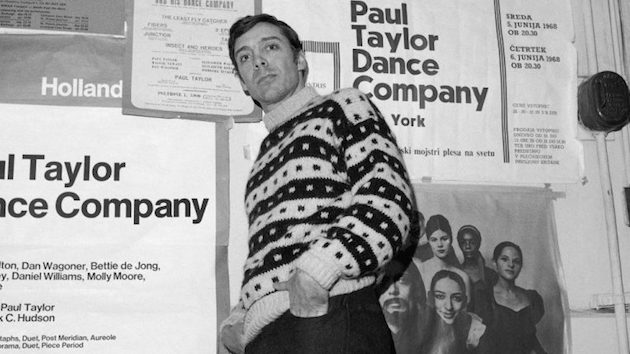

Corrections: As originally published, this article incorrectly identified the photo above showing a scene from Diggity as an image from Esplanade. It also incorrectly identified Ralph Vaughn Williams as the composer of the music for Sunset. The composer was Edward Elgar.