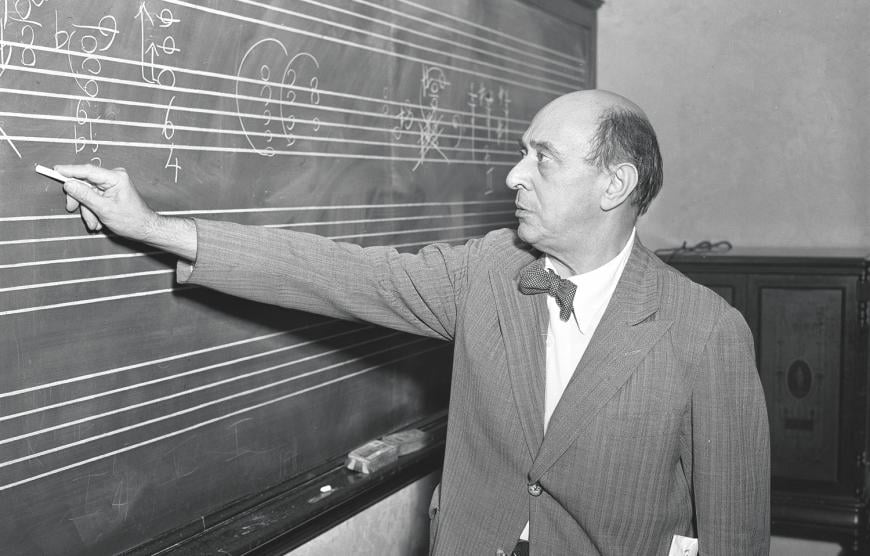

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) probably would have relished having his 150th birthday on Sept. 13, 2024, celebrated. He wasn’t shy about his intention to extend the dominance of the German musical tradition. He supposed this could be done by pushing beyond the harmonic language of Richard Wagner into atonality and eventually his own 12-tone system, a method of composing that treats all notes of the chromatic scale equally.

Schoenberg knew it wouldn’t be easy. Few composers have been as virulently attacked in their lifetimes. His writings, like the essay with the self-pitying title “How One Becomes Lonely,” are often loaded with paranoia. But he didn’t lose hope that someday audiences might get it.

And yet, even 112 years after the premiere of his atonal song cycle Pierrot lunaire, the name Arnold Schoenberg still elicits fear and loathing from a good portion, possibly a majority, of classical listeners. Granted, the quality of performances of his work has greatly improved. Musicians today are much better equipped to navigate thorny passages and make them flow comprehensibly. But a mass audience for atonal music still doesn’t exist, and after a 100-year-long trial, we can conclude it probably never will.

Most likely due to a perception of Schoenberg as something of a musical bogeyman, commemorations of the Austrian composer’s sesquicentennial this year have been sparse in the U.S., though plentiful in Europe, especially Germany. This even seems to be the case in the city in which he chose to spend the last 17 years of his life — Los Angeles.

The late Santa Monica concert series Jacaranda made the most enterprising effort earlier this year before the organization shut down due to lack of funding. Not until this month did the Los Angeles Philharmonic launch “Schoenberg at 150,” which consisted of just three works spread over one chamber music concert (on Dec. 3) and one subscription concert (performed Dec. 13 and 15). That latter program was taken up by the gigantic, über-Romantic symphonic song cycle/cantata Gurrelieder.

If you were looking for another of the LA Phil’s imaginative, boundary-shattering festivals that would put the composer’s music and influence in new perspective, you’d have been disappointed. There was no atonal nor 12-tone work on either of the Phil’s programs, which concentrated solely on Schoenberg’s earlier compositions, before he went over the edge. The orchestra’s festival spills over slightly into 2025 with a single work on the Feb. 13–16 subscription program, but it’s a fanciful orchestration of Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 1. Nevertheless, give the Phil credit for squeezing its limited agenda into two quality packages this month.

The chamber concert at Walt Disney Concert Hall on Dec. 3 was a gem. While Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured night) is Schoenberg’s most played piece, I imagine it can still surprise listeners who have been led to believe that all the composer’s music is forbiddingly difficult. This was his first out-and-out masterwork in a late-Romantic, Wagner-drenched idiom, with tunes that stay in the mind and a morbid, hothouse atmosphere that ultimately resolves into delicate, floating peace. And yet, in his liner notes to a 1950 recording by the Hollywood String Quartet that he supervised, the ever-rueful Schoenberg wrote, “It should not be forgotten that this work, at its first performance in Vienna, was hissed and caused riots and fistfights. But very soon it became very successful.”

The sextet from the LA Phil — violinists Johnny Lee and Rebecca Reale, violists Jenni Seo and Dana Lawson, and cellists Robert deMaine and Jason Lippmann — had its rough edges of ensemble in the beginning, but the dynamic contrasts were wide, and they captured the intensity of the stormy passages. First violinist Lee supplied plenty of portamento, and deMaine gave a lovely cello solo down the stretch. This interpretation leaned more into the piece’s 19th-century roots and less into its implications for Schoenberg’s future directions.

This year would have been the perfect time to program the five string quartets, which tell the story of the composer’s extraordinary evolution more completely than any set of quartets since Beethoven. The saga actually begins with the first unnumbered Quartet, rooted in Brahms and with side trips through Antonín Dvořák; progresses to the designated First Quartet, where Wagner’s influence takes over; and then moves to the dramatic Second Quartet, in which Schoenberg takes the momentous leap, in real time, from tonality to atonality. The Third and Fourth Quartets, written several years later, are 12-tone works yet, when placed in the context of the preceding pieces, are clearly meant to extend the German tradition.

Hearing the First Quartet, though, was certainly enough to complete Tuesday’s chamber concert. Already, the language from Verklärte Nacht shifts into another gear, naggingly contrapuntal, chromatic and restless, pulling and tugging at tonality, seemingly trying to break out of it but still rooted firmly in the past. Despite its sprawl, complexity, and not-easily-discerned form, hearing the quartet is a gripping experience. The flow of the complex rhetoric pulls the listener along in a total fusion of heart and mind.

The music received a terrific performance from LA Phil violinists Bing Wang and Emily Shehi, violist Ben Ullery, and cellist Dahae Kim. Their passion for the music was obvious. Ullery, in his preperformance remarks, said that he had been begging the Phil for years to let him play this quartet. And it couldn’t have been easy physically to sustain this much fervor and technical effort for 50 uninterrupted minutes. Not only that, the group sounded considerably more cohesive than the earlier sextet, handling the turbulent passages brilliantly and coming to a soft landing at the end of a drawn-out coda.

As for Gurrelieder, which was begun in 1900 but not completed until 1911, it was an instant hit at its belated 1913 Vienna premiere precisely because it was a throwback to, and a summation of, a Romantic era that Schoenberg thought was on its last legs. It was the biggest concert triumph of his career. Was he happy about the response? Not at all, for he figured that the plaudits had gone to the old Schoenberg of 1900 and not the current, evolved Schoenberg of 1913.

In any case, Gurrelieder was certainly a resounding hit at Disney Hall on Sunday afternoon, Dec. 15. This performance is going to be talked about and remembered for many years to come. Zubin Mehta, who introduced the piece to Los Angeles in 1968 when he was the LA Phil’s music director and repeated it in 1977, led a splendid, exciting, and beautifully played and paced rendition. The Phil is a more skilled ensemble than it was in 1968, housed in a more acoustically balanced hall — and Mehta, now a wise old master at 88, took full advantage.

He set the glittering, magical prelude at a slower pace than one usually hears, bearing a relaxed rhythm that let the music breathe naturally. As a result, a staggering number of luscious details were revealed and clarified.

One thing that Mehta does whenever he conducts a huge Romantic piece these days is time the buildup to a climax so that it explodes with maximum impact at exactly the right moment. You can thank long experience for teaching him that. From his seat on the podium, he exerted total command over the ensemble of hundreds with a minimum of gestures, a demonstration of “less is more” taken to the max.

Mehta also had the advantage of having one of the leading Wagnerian sopranos on the planet, Christine Goerke, at hand to sing the role of Tove, and she unleashed huge torrents of sound that easily rode over the augmented orchestra with its 11 horns (four of them doubling on Wagner tubas), multiple winds, and four crimson-colored harps.

Tenor John Matthew Myers, stepping in as Waldemar at the 11th hour for Brandon Jovanovich (who canceled due to illness), sang capably if not with the amplitude of Goerke. Mezzo-soprano Violeta Urmana warbled the Song of the Wood Dove with tremulous power, tenor Gerhard Siegel was an excellent Klaus the Fool, baritone Gabriel Manro had his brief part as the Peasant memorized, and veteran baritone Dietrich Henschel produced an authentic, forthright display of the specialized art of Schoenbergian Sprechstimme (speech-song).

The Los Angeles Master Chorale let it rip in the hunt scene and blazed resplendently in the final chorale. (The performance was dedicated to one of the Master Chorale’s founders, Marshall Rutter, who died earlier this month).

Disney Hall looked packed to the rafters for this concert. It could be that Mehta was the main drawing card, but let’s give the composer the credit for the big turnout in his adopted hometown.