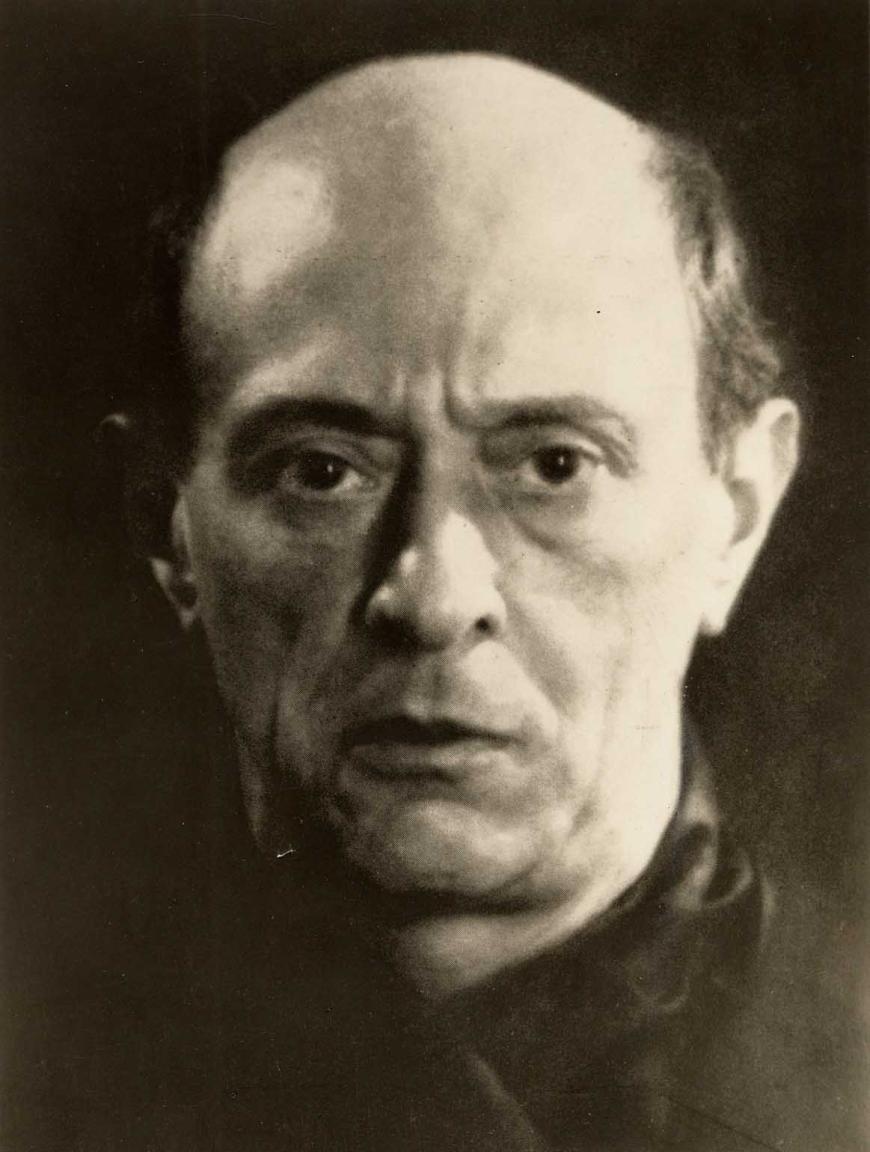

Arnold Schoenberg, among the most influential composers of the 20th century, turns 150 this year, and yet his music is not being heard much in the Bay Area. West Edge Opera brilliantly staged his monodrama Erwartung in 2023, and the San Francisco Symphony will perform it in June. To the south, Zubin Mehta will lead the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the composer’s enormous oratorio Gurre-Lieder next season.

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players (SFCMP) stepped up to fill the obvious gap with a two-concert mini-festival, “Pierrot RE:wind,” focused on and around Schoenberg’s enormously influential 1912 work Pierrot lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot). Schoenberg composed Pierrot for an idiosyncratic chamber ensemble of singer, violin/viola, cello, flute/piccolo, clarinet/bass clarinet, and piano, and in the century since its creation, the song cycle has spawned numerous works with similar instrumentation, as well as groups dedicated to playing them.

Pierrot sets 21 richly symbolic poems by the Belgian poet Albert Giraud, translated from the original French into German. The poems feature the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot, who wanders, perhaps drunkenly, through the night, singing of moonlight, black roses, wine, blood, illness, religion, death, historical characters, and his home in Bergamo.

Schoenberg hadn’t yet codified serialism when he composed Pierrot, which is written in a lush, freely atonal style. It’s a great match for the haunted decadence of the poems, and the piece’s sound world is remarkably varied and colorful despite its small ensemble.

Pierrot, by far the longest work in SFCMP’s festival, closed out the second program, “Pierrot RE:encountered,” on April 21 and received a bravura performance from mezzo-soprano Rachel Calloway, violinist Hrabba Atladottir, cellist Doug Machiz, flutist Tod Brody, clarinetist Peter Josheff, and pianist Allegra Chapman. For this performance, SFCMP commissioned animations by artist Simona Fitcal, who based her work on Schoenberg’s own paintings. Additional art was by no means necessary, given the intense imagery of the poems, but the animations appropriately matched the moods of Pierrot and gave a glimpse of a different facet of the composer’s artistry.

Calloway gave a virtuoso account of the demanding vocal part, which calls for a great deal of Sprechstimme (speech-voice), a vocal style that requires the performer to half-sing, half-speak the text. The score gives the singer leeway on just how to execute this, and Calloway leaned toward mostly singing. She sang with an exquisite palette of vocal color — from the driest sound to the warmest — and with exceptional, nearly instrumental, rhythmic articulation of the text.

That variety is utterly necessary: Schoenberg asks the singer to nearly whisper, to nearly shriek, to laugh, to moan. The instrumentalists match that colorful writing with trills, harmonics, flutter-tonguing, and other extended techniques. The music can be utterly gorgeous or grimly fate-filled. And while there aren’t stage directions, Calloway’s posture, the angle of her head, her facial expressions, the movements of her arms, conveyed the story physically as much as her voice conveyed the texts musically.

Most of the companion works for SFCMP’s festival were published in this century, save for a couple exceptions. Schoenberg’s 1901 songs “Der genügsame Liebhaber” (The contented suitor) and “Mahnung” (Warning) appeared on the first half of Sunday’s program. You would likely not recognize these louche, delightful, and thoroughly tonal cabaret songs as Schoenberg’s without a program note, dealing as they do with a voluptuous woman’s velvety black cat and a young woman who might be wasting her time, romantically speaking.

Also on that program were Joan Tower’s brief Petroushkates (1980), a charming riff on the opening of Igor Stravinsky’s great ballet score Petroushka, and Jessie Montgomery’s Lunar Songs (2019). That latter work, for string quintet and voice, is an homage to Pierrot and was written for the centennial of Leonard Bernstein’s birth. J. Mae Barizo’s poems reference the moon, various natural features of the Earth, Bernstein’s political activity, and New York City, the conductor’s home for many years. The first song is almost bluesy, the second features a rocking, offbeat time signature, and the third is all gossamer and harmonics.

Of all the works performed during the festival, it was Massimo Lauricella’s 1996 E piove in petto una dolcezza inquieta (A restless sweetness reigns in your breast), a West Coast premiere heard on Saturday, that most closely resembled Pierrot. Lauricella’s piece sets a poem by Eugenio Montale, “Ossi di seppia” (Cuttlefish bones), whose imagery includes the edge of a blade, “ice so tense that it cracks,” letters of fire, shadows, and the soul. The vocal part, sung with a bright instrumental tone by soprano Winnie Nieh, felt like it walked a knife’s edge.

Sprinkled throughout that first program, “Pierrot RE:imagined,” were the movements of Andrew Norman’s Mine, Mime, Meme (2014). They’re intended to be split up, though SFCMP Artistic Director Eric Dudley said in his remarks that one is so short, at under a minute, that they could be played together.

The first movement sounds like the tuning at the start of an orchestra concert, the instruments all entering on the same pitch. They then echo each other in repeating, scattered, out-of-sync phrases. The second movement features sliding phrases that move from instrument to instrument. The final movement has a section that heads toward the world of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and another with cascading, tumbling phrases nearly tripping over each other. The music becomes more lyrical and meditative, then dies away in more phrases of short duration.

Norman’s piece was beautifully performed by Josheff, flutist Brittany Trotter, pianist Keisuke Nakagoshi, percussionist James Beauton, violinist Susan Freier, and cellist Stephen Harrison, in various formations. Clarinetist Jeff Anderle and percussionist Divesh Karamchandani also played on “Pierrot RE:imagined,” as did Atladottir, Machiz, Brody, and Chapman. Where a conductor was needed — which was for most of these works — Dudley conducted with unobtrusive clarity.

Three additional pieces rounded out Saturday’s program. Kevin Day’s perky and pretty un(ravel)ed (2019) featured broad melodies and a good deal of interplay among the instruments, which included marimba. Mason Bates’s Difficult Bamboo (2013), some 20 minutes long, overstayed its welcome. Bates seems to have incorporated every passing musical idea here, which made the audience think the piece was over at least three times before it finally concluded. Katherine Balch’s Musica Spolia (2021) is a delightful collection of found sounds, inspired by Rome’s vines and objects placed in the walls and other public places of the city. Balch’s piece had by far the largest variety of sounds on the program, owing to the range of objects used as percussion. I wish it had been twice as long.