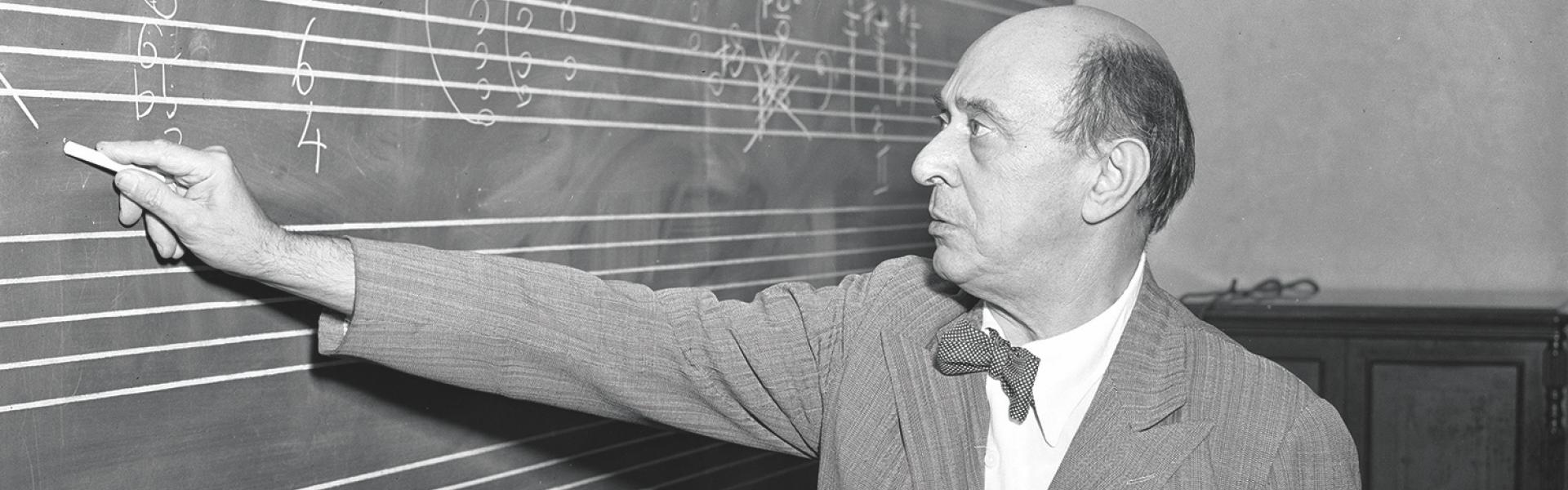

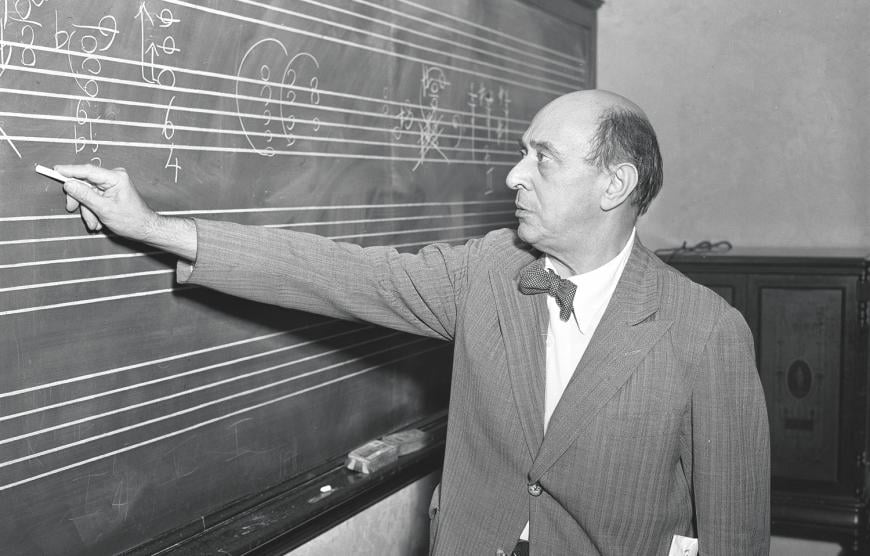

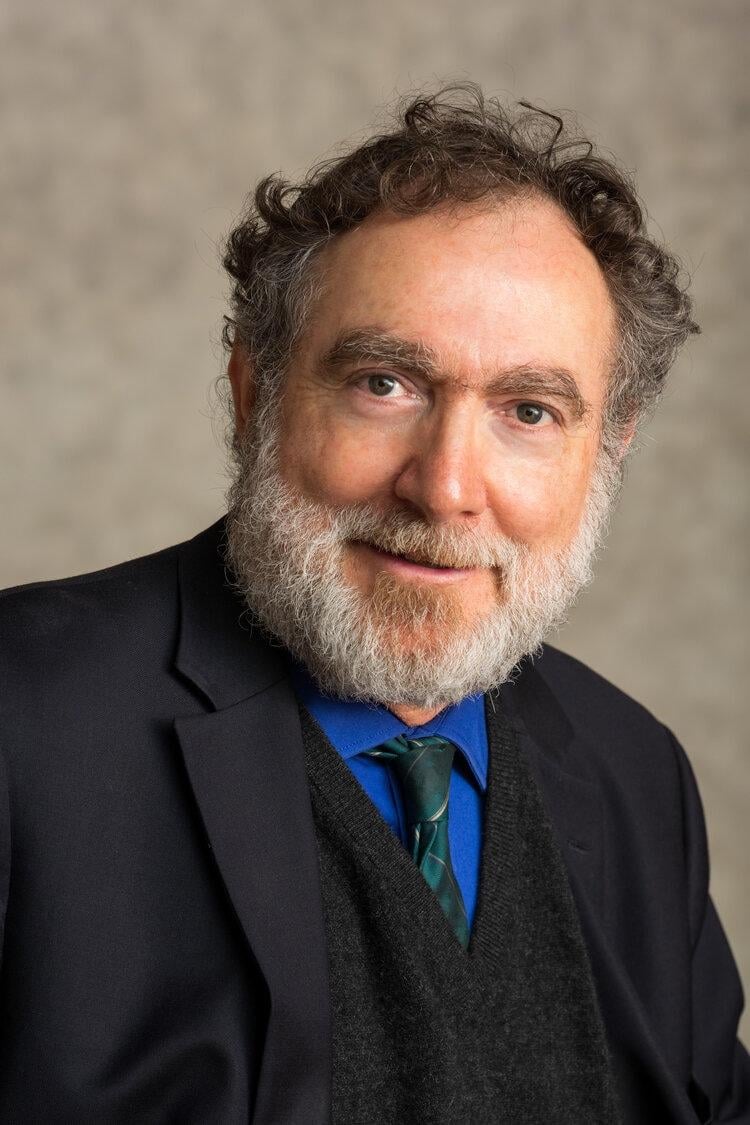

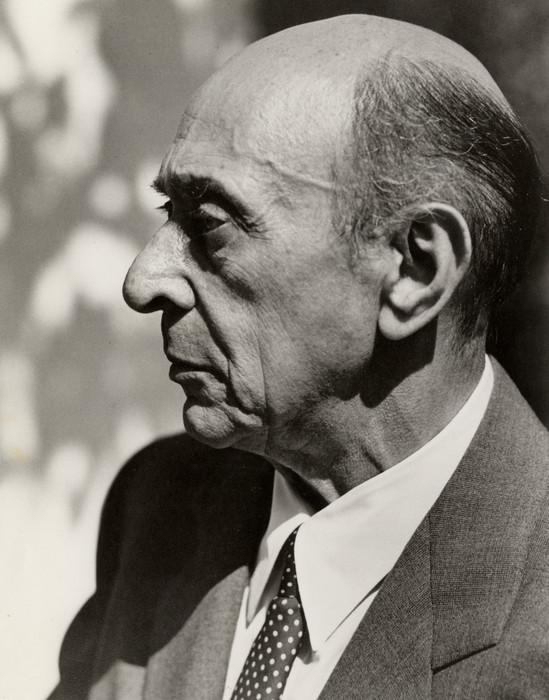

Arnold Schoenberg was born on Sept. 13, 1874 — almost 150 years ago. Jonathan Khuner was born in 1948, making him roughly half as old as Schoenberg would be today. And yet, there’s a connection between the two men, which the prominent Bay Area conductor is set to explore in a series of lectures next month.

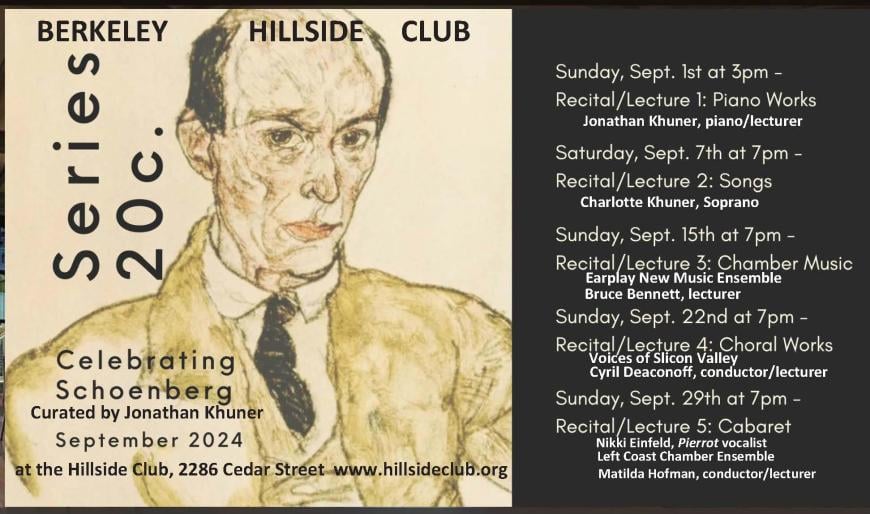

In five events, Sept. 1–29 at Berkeley’s Hillside Club, Khuner, musical director of West Edge Opera, will offer an exploration of Schoenberg’s “wide range of genres and styles, from Romantic to atonal and dodecaphonic.”

By way of introduction to the composer, Khuner says, “Schoenberg’s music is thorny, but there’s always great beauty and powerful expression waiting for you to find through careful, repeated — and in this case, guided — listening, without academic posturing or theoretical jargon.”

The lecture-demonstrations will feature sopranos Nikki Einfeld and Charlotte Khuner, composer Bruce Bennett, violinist Terrie Baune, violist Ellen Ruth Rose, cellist Thalia Moore, Left Coast Chamber Ensemble, and Voices of Silicon Valley.

About his personal connection to Schoenberg, Khuner says, “I’ve created this series on Schoenberg as a private homage to my eccentric father. As a teenager, [my father] veered off the academic track in Vienna in 1926 to follow the Schoenbergian cause [as a member of] the Kolisch Quartet, and this temporary detour led to his survival in World War II and to his postwar engendering of a California family.

“Thus, I owe my existence to a paternal penchant for new music, which I also inherited.”

That father, violinist Felix Khuner (1906–1991), joined the renowned Vienna-based Kolisch Quartet at age 19. During the Quartet’s first U.S. tour in 1935, he applied for permanent resident status here, which later protected his family from destruction by the Nazis.

Leaving Austria before the war and the Holocaust, which destroyed so many lives, Felix Khuner lived in Berkeley and joined the San Francisco Symphony in the early 1940s, staying in the first violin section until 1973 and with the San Francisco Opera Orchestra until 1983. He also founded and led the California String Quartet and played with Oakland’s Prometheus Symphony Orchestra — both ensembles known for championing new music.

The younger Khuner adds his own history:

“I grew up in a house reverberant with much ‘modern music,’ as the California Quartet played an amazing sequence of concerts over those years, always with a new piece on the program. At some point in my piano studies — age 13? — I fished the Schoenberg piano pieces out of my dad’s music bookshelf and started investigating at the keyboard.

“After a month of ingesting the material through my fingers and ears, I felt a flash of new recognition of what music really meant, or could mean — so different from what I had been hearing in all my standard student repertoire of the Bach-Beethoven-Brahms orientation, though clearly just a few steps further in the same line of technique and aesthetic.

“After that, I took up every opportunity to hear and play new music. My father was not forthcoming about his personal history, but I knew that his early career had been founded on performing music of the Second Viennese School [the group of composer gathered around Schoenberg]. And [my father] did offer musical advice, express opinions, and exemplify attitudes that reflected the thought and musical works of Schoenberg, whom my dad acknowledged as his closest friend and mentor in all things musical.

“It was a whole way of experiencing and valuing music that involved careful and deeply detailed listening, plus the rejection of superficial or pandering art. My father had been iconoclastic and cynical from an early age, it seems, cherishing his search for the unvarnished truth of musical meaning and scorning all impure impulses in performance: banality, showmanship, egoistic distortion, popularity-seeking, [and so on].

“It goes without saying that my musical taste grew within that hothouse. Italian music, with its easy emotionality, was suspect. French impressionism was insubstantial. [Igor] Stravinsky was OK but impoverished by lack of commitment to organicity.

“This attitude has stayed in my core, with modifications and the gradual acceptance of all the less mindful and nonintellectual ways that music can be part of life. So I no longer mind [for example] that operagoers love to be dazzled by brilliant costumes and bowled over by powerful, beautiful voices, not to mention the basic pomp and splendor of opera-house presentation.”

Indeed, in spite of those early feelings, Khuner has successfully conducted hundreds of opera performances with a dozen different companies, even taking Richard Wagner to Albania and a contemporary work to Nepal.

To explain his “gradual acceptance” of music more popular than intellectual, Khuner says, “I simply go my own way of searching for life and meaning. … I guess it’s a combination of different levels of beauty and significance.

“For several years, 2000 to 2004, I led an opera performance course at UC Berkeley; that was a fine channel for spreading acquired knowledge. Of course, promulgating my beloved modern music — if Second Viennese School compositions still count as such — has hardly ever been possible, except in the context of productions I could conduct, such as Lulu and Erwartung at West Edge Opera. Over the years, Schoenberg’s value has been increasingly ignored, and I had felt helpless to remedy the situation.”

Ignored in the U.S. maybe, but not in Europe. The 150th anniversary of Schoenberg’s birth is being celebrated in many cities, especially the composer’s birthplace, Vienna, where 50 institutions are joining forces to host more than 200 events in 30 locations this year under the heading “Schönberg 150.”

In the Bay Area, it was up to Khuner to pay attention:

“About two years ago, it occurred to me that the 2024 sesquicentennial of Schoenberg would be an ideal time to return to my youthful enthusiasm. It seemed almost obligatory to honor the prime mover of my father’s musical ideology and a mainstay of mine. In the 1960s and ’70s, I had observed Joseph Kerman’s very successful lecture-recitals at Cal — with chamber musicians in Hertz Hall — and his format of performance-lecture-repeat performance seemed ideal.”

Unlike the major series of events marking the Schoenberg centennial at UC Berkeley in 1974, there was no interest from large organizations this time. So Khuner focused on a “sandwich-concert” idea, as he puts it, fleshing the series out with pieces from all of Schoenberg’s periods and in a variety of genres. Supported by the area’s contemporary music groups and the Hillside Club, this celebration of Schoenberg is now set to become reality.

The plan is to introduce Schoenberg’s music by “pointing out bit by bit what actually is going on,” says Khuner. “How he builds melodies, how his music is always an organically growing fabric, how literal repeats are not the basis for building structure but are used in special circumstances.”

Khuner continues, “Schoenberg explored new harmonies, trying to tie them together and plumb the possibilities of a para-tonal vocabulary.

“I’m even planning on audience participation, humming along with bits of tunes so that we can all experience the lilt of an atonal phrase and even the singability of 12-tone palindromes.

“So often there are many strands going on at the same time. … I will dissect them so that the audience gets familiar with each part of the texture and discovers the joy of hearing and discerning many independent moments and lines within a rich texture.

“Likewise, we can get accustomed to the unfamiliar sounds of dense harmonies and how they are used for beginning, middle, and end points of Schoenberg’s musical stories by ear-analyzing and repeated illustration of these new chords. The singer-reciter also can sing over important bits until they worm [themselves] into the listener’s ear.

“For the compositions [with text], I’ll be discussing how Schoenberg responds at every level to the poetry, sometimes to the meaning of a word, sometimes to the direction of the phrase, but always to the emotional complex of the poet-performer’s persona.”

Khuner says his aim is to demonstrate that “Schoenberg was trying not to break old bonds, nor to establish rigid new ones, but to allow his inner impulses and reactions to be transmitted in the aural medium with all the richness of overall experience itself.

“I’ve asked the other lecturers to take a similar approach but can’t vouch for their adoption of my style at all. In fact, I hope that each of them will share their own story of how they came to know, enjoy, and love this so complicated music.”