It turned out to be one of contemporary music’s most productive border crossings (without walls) when the minimalism of Philip Glass stimulated the rock ’n’ roll imagination of David Bowie and Brian Eno. The result was a succession of albums in the late 1970s that would become known collectively as “The Berlin Trilogy.” But that was not the end. Glass was so impressed by the albums that in 1992 he adapted material from Low to create his Symphony No. 1, followed in 1996 by his Symphony No. 4 (“Heroes”). The process of finalizing his Bowie/Eno trilogy, however, proved considerably more elusive, until Thursday.

Exactly three years to the day after the death of David Bowie, Phillip Glass’s Symphony No. 12 (“Lodger”) received its world premiere with the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by John Adams. But with changes being made to the score almost to the moment of the premiere, and only two days of rehearsal, it’s not surprising the performance was more than a bit rough around the edges. But the truth is, the shortcomings in “Lodger” are far deeper than that. Its combination of been-there-done-that musical formulas and ill-fitting music and lyrics simply doesn’t work. The symphony feels tired when it should be energizing, lackadaisical when it should be edgy, suffering from a lack of originality and dramatic focus.

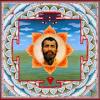

Even stalwart David Bowie fans have a hard time dealing with his Lodger and its 10 songs representing a strange, emotionally conflicted travelogue of the rock star’s life. The album has even been described as approaching self-parody. Nevertheless, several of the songs, particularly the sexually ambiguous “Boys Keep Swinging,” “Fantastic Voyage,” which opens the album, and the self-referential “Look Back in Anger” have real impact, particularly in their music-video incarnations. But whereas Glass found gems of musical inspiration in the Low and “Heroes” albums, the music of Lodger, he has admitted, left him cold and uninspired.

Either through a sense of obligation to his late friend, or the necessity of completing a multi-orchestra commission, Glass was determined to mold Lodger into a symphony. The critical turning point came when he decided to jettison Bowie and Eno’s music entirely and focus instead on the lyrics, transforming his Symphony No. 12 into a six-movement song-cycle. Then, rather than going with an operatic or classically trained vocal soloist, or a balls-out rock star, Glass decided to cast Angélque Kidjo, described by Time Magazine as, “Africa’s premier diva,” in the leading role.

Kidjo (who comes from the West African country of Benin) is more of a chanteuse than a rocker. And at least at this point, she seems unsure of how to interpret and sell Bowie’s lyrics, which vary from introspective poetry to socially provocative commentary and issue-oriented themes like male identity and sexual assault. As reflected in the album’s title, memories related to travel function as a metaphorical through line.

As a performer, Bowie combined an immense amount of personal flair with the bite of a hard-edged rocker to sell his songs. His vocals were combined with a barrage of back-up music powered in no small part by Eno’s inventive use of electronics and rhythm. It was not uncommon for Bowie’s singing to all but disappear into the overall texture of a song repeating key phrases again and again like a rock mantra.

Kidjo is far too restrained, vocally and emotionally, to rock out, and too vague in her interpretations to provide the necessary dynamic contrast with Glass’s massively orchestrated score. The lyrics, which were composed to the beat of entirely different music, feel awkward and pasted on. It isn’t until the final song, “Red Sails,” with its haunting melodic references to “The Train” from Einstein on the Beach, that soloist, orchestra, and lyrics came together in a thematically cohesive and musically evocative manner.

As John Adams said during the preconcert talk led by Sarah Cahill, it takes “all of a millisecond” to know you’re listening to a Philip Glass composition. The problem is there is really nothing new to listen to. The Mahler-scale orchestration, plus the magnitude of the Disney Hall organ (performed by James McVinnie) is as overstuffed as a lumpy couch. The modulations and variations are too familiar. It’s possible that by the time the work has its next performances in May with the London Contemporary Orchestra, a new and improved version will emerge, but it seems unlikely.

The first half of the program was very different, contrasting Tumblebird Contrails by Berkeley composer, Gabriella Smith (commissioned by and premiered at the 2014 Cabrillo Festival), with the rollicking, exuberance of Adams’s 1982 Grand Pianola Music.

Composed as a site-specific rhapsody on nature, Smith combines unique instrumental effects (particularly in the percussive use of the strings and lowing bellows of the brass) to create a visceral evocation of the Point Reyes National Seashore with its crescendos of ever-rolling waves, hovering flocks of screeching gulls, and hissing pebble beaches. It’s a piece that totally accomplishes exactly what it set out to do — hold a musical mirror up to nature. Currently completing her studies at Princeton, Smith is a composer you should keep on your radar.

What is there to say about Grand Pianola Music that hasn’t already been said? “It’s a classic.” That’s how Sarah Cahill described it. To which John Adams quipped, “If I’d known I was writing a classic, I would have worked on it longer!”