Erich Wolfgang Korngold, the onetime Austrian boy wonder who became one of the most influential composers of American film scores, wanted his legacy to be more than that. After leaving Warner Bros. in 1947, he spent the remaining decade of his life composing concert music, the most imposing piece being the Symphony in F-Sharp Major from 1952.

Korngold meant it to be a purely musical experience with no program attached, but when the symphony premiered on Austrian radio in 1954, critics didn’t buy that idea. The composer was still tainted by his Hollywood association, and few took him seriously. The work wasn’t performed in concert until 1972 and was then recorded in 1974 by Rudolf Kempe and the Munich Philharmonic. By that time, Korngold’s film music was being reevaluated thanks to records supervised by the composer’s son, George. Although there are several recordings available, the Symphony in F-Sharp is still a stranger to concert halls, even in Korngold’s adopted hometown of Los Angeles.

But from out of left field, a pair of archival recordings have been released in a single package from Supertrain Records. These two discs may perhaps alter perceptions of what the symphony is about. Right in the thick of this project is John Mauceri, the former conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra whose unflagging championing of film composers continues to pay off.

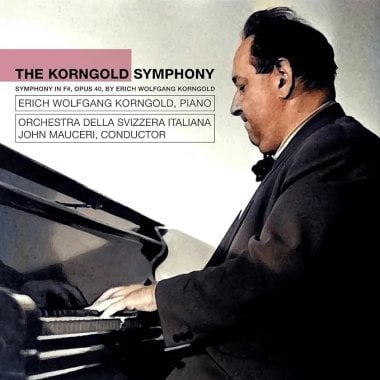

On one disc, Supertrain has issued a 1997 live radio performance of the symphony by Mauceri and the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana. The second disc contains the big news: a private recording, made in Hollywood sometime between 1952 and 1954, of Korngold himself playing his symphony on the piano.

Mauceri has a specific interpretation in mind. Based on the score’s dedication to the memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the wild urgency of Korngold’s playing on record, and information gathered from personal contact with the composer’s descendants, the conductor suggests that that symphony is a portrait of World War II in all its agony and joyous aftermath, with warnings that it could happen again.

Well, maybe. Perceptions in music are personal, and to me, Korngold’s powerful, sprawling post-Romantic symphony in four traditionally organized movements brings to mind William Walton’s First Symphony, another underappreciated masterpiece, written before the war, with a similar structure and trajectory from agitation to mourning to triumph. (Interestingly, Korngold, in his Main Title for the movie 1942 Kings Row, did a pretty good impression of Walton.)

From the first chords of the Symphony in F-Sharp, we hear a striking departure from the Korngold of the movies. We enter instead into a world full of ambiguity, impending doom, even dissonance. Mauceri’s tempos are definitely slower than Kempe’s (and Korngold’s own recording, too) — as they are throughout the 1997 performance. Yet while Mauceri shows more emphatic conviction, Kempe’s first movement is more logically organized and better held together, easier to grasp and with not as much sprawl.

The kinship with Walton’s First is clearest in the second-movement Scherzo — agitated, nervous, enormously vital. Here, Kempe displays more urgency than Mauceri; the Italian-Swiss orchestra seems to be playing the difficult figures reluctantly.

Mauceri ranks higher than Kempe in conveying the tragedy of the Adagio third movement, rising to near-melodramatic levels near the end, in line with a political reading of the score. The sprightly theme of the Finale is handled gently by Mauceri — and I think he’s right that the literal borrowing of the tune of George M. Cohan’s “Over There” is a specific reference to the war.

Korngold’s archival recording is, of course, invaluable. We hear the composer’s own accented voice announcing each movement and counting off the beat. Much of the first movement sounds brutal and virtually atonal. The Scherzo excerpts are zipped through at an impossibly fast pace, the composer pounding away in jagged, frenzied form, like Charles Ives in his piano demos. The Adagio has the grandeur of a Chopin prelude, treated in a Romantic manner that clearly rubbed off on Mauceri’s performance. Korngold’s timing is erratic in the Finale, yet he flails at the notes with gusto. The mono sound sometimes flits back and forth between the speakers yet is listenable.

Always absorbing and erudite in his extensive booklet notes, Mauceri writes that Korngold’s recording “became my guide, and always will be,” but Supertrain founder Richard Guérin notes elsewhere that “Mauceri’s performance is his own.” And so it is. We’re fortunate to have both available.