The St. Lawrence String Quartet (SLSQ), long resident at Stanford University, has had a fruitful relationship with composer John Adams, who wrote his two string quartets and the quartet and orchestra piece Absolute Jest for them. They have now taken up the music of his son, Samuel Carl Adams, and on Sunday, February 18, the string quartet made it a family affair, performing the three quartets written by the composers.

Discussions among the performers and composers resulted in a change of the original program order, and the works were played in reverse chronological order of composition, with John’s Second Quartet (2014) first, followed by Samuel’s String Quartet in Five Movements (2013), and John’s First Quartet (2008) closing out the program.

That Second Quartet comes from the same wellspring as Absolute Jest, mining the works of Beethoven for musical fragments to throw into the hopper of John’s imagination and see what comes out. The program notes state that both the First Quartet and Absolute Jest underwent significant revisions both before and after their premieres. In the case of Absolute Jest, this amounted to making a large cut and rewriting the opening 400 measures.

Hearing the Second Quartet, I can’t help but think that it needs some reworking as well. In this piece, Adams riffs on and around fragments from Beethoven’s Op. 110 piano sonata, his next-to-last, and the Diabelli Variations. The results have none of the quicksilver fun of Absolute Jest. The first movement has so much roughhewn, double-forte sawing at the instruments as to leave me scratching my head and wondering whether the composer or the performers had simply lost all sense of subtlety. It has to be intentional on Adams’ part, perhaps an homage to Beethoven at his most bumptious. Unlike the earlier master's works, however, this quartet doesn’t have much joy or wit to it, or much differentiation and contrast among the instruments.

In his remarks, Adams characterized the second movement as more lyrical than the first, yet it was rather unsubtly overwrought instead. The Second Quartet might work better with a larger string ensemble, but more likely it would benefit from a rewrite.

In his remarks before the String Quartet in Five Movements, Samuel Carl Adams told us that his quartet contained many fragments, dozens, from string quartet history, with most passing rather quickly through the piece without much elaboration. I could not identify many of these, and it seemed as though the composer was riffing as much on the general style of past masters of the quartet as he was borrowing from them.

This quartet is a work of considerable variety, and not just because of the historical references. The very texture of the sound changes moment by moment, with constant shifts in voicing, vibrato, harmonics, pizzicato, bowing on the bridge, and other techniques. Adams has a knack for creating stillness in his music by slowing down the harmonic rhythm and giving the players beautiful harmonies to sit with. One movement has the word “austere” in its title, but it’s not the only movement to have a certain reserved fragility about it. Bartók, who Adams didn’t mention, might be one the spiritual fathers of this lovely quartet. The SLSQ, to whom the work is dedicated, played with their customary flair and focus, delicately or robustly as needed, vanquishing any thoughts that they might be playing at less than their typical level of accomplishment.

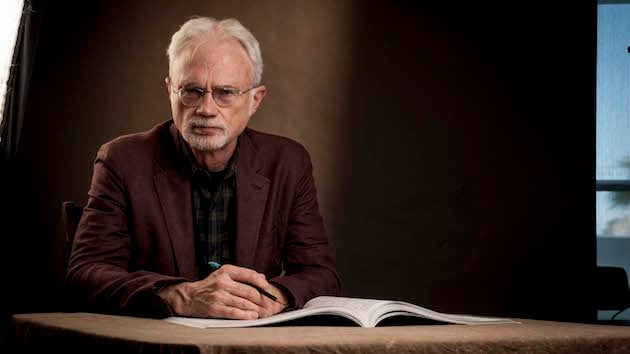

“You can imagine how proud I am,” said John Adams after the intermission, when he came out to introduce his First Quartet. Yes, we can, given the striking beauty of Sam’s quartet and his command of string writing. And John’s First Quartet was a powerful reminder of how great a composer he is at his best: witty, entrancing, lively, idiosyncratic.

The First Quartet is oddly proportioned, as the composer said, with a first movement that’s considerably longer than the second, and which is divisible into subsections that can almost stand on their own. It’s marvelously inventive, making striking use of extended trills and providing a cadenza-like solo for the first violin. The second movement is a neat spinning wheel of crackling energy, with a tremendous crescendo and stretto at the close. While it was written long past the point where “minimalist” seemed like the right description of John Adams’s style, the composer’s handling of rhythmic variation in the movement sounded minimalist. Again, the SLSQ played it like the masters that they are.

The concert ended with a standing ovation for the composers Adams and the quartet, who had a genuine lovefest on stage, applauding and hugging and looking very pleased with the performances.