Having by chance been scheduled to interview two Adamses on the same afternoon — first Sam, for SFCV, then John, for another publication — I was impressed by their physical similarity and intellectual kinship, as well as by their shared individuation as composers. The coincidence is compounded in that chamber pieces by son and father (respectively), composed for and performed by the St. Lawrence String Quartet, will appear on the same Hertz Hall program on Sunday, Feb. 18. Like John (who inherited a love of classical music and the clarinet from his own father), 32-year-old Sam Adams started studying and performing while a child, attending school at Berkeley’s Crowden Music Center (with his older sister Emily) and participating in the Bay Area’s improvised music community. At Stanford, he earned a bachelor’s in composition, integrating digital technology into his writing at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics.

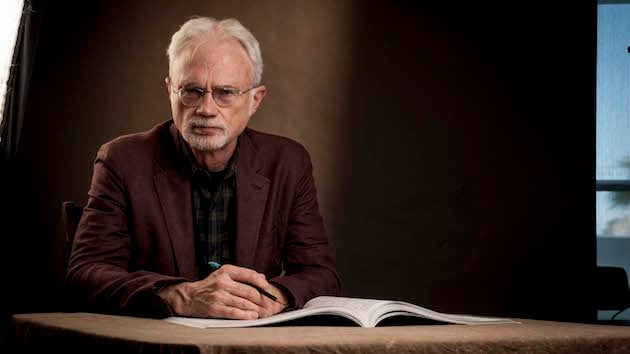

Adams went on to a master’s in composition at Yale, became a teacher himself in New York City, where he also designed theatrical sound installations and played bass in contemporary and jazz ensembles. He soon began receiving commissions from Carnegie Hall, the New World Symphony, and the San Francisco Symphony. Aside from orchestral works, he’s written for small instrumental and electronic ensembles, and co-curated the contemporary MusicNOW series for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), where he’s completing a residency. About a year-and-a-half ago, after several years in New York City, Adams relocated to the city of his raising and returned to Crowden as a teacher in his father’s Young Composers Program. His composition many words of love was performed by the CSO on tour earlier this month at Carnegie Hall. His chat with SFCV took place earlier this week at his new studio in Oakland.

What motivated your move back home?

I’d been in Chicago, splitting my time between there and St. Louis, where my at-that-time girlfriend [violinist Helen Kim] was working with the St. Louis Symphony. Then she took a job with the San Francisco Symphony [where Kim is now principal second violin], we got married, and I’ve been working and writing here since then, and living in North Berkeley. We’re both Westerners, and wanted to be back by the Bay; she grew up in Reno, and went to USC.

Is California the right place to be doing what you do?

I think there’s a sense of openness here, and an intellectual and philosophical freedom. It exists in the traditions of Californian and Western art, when you look at Agnes Martin, Georgia O’Keefe, or Kerouac, and, to a certain extent, my old man. These are artists who decided to come West to escape a kind of establishment, to find an artistic society that didn’t necessarily have a historical burden. And I also came back because of work. I have a relationship with the San Francisco Symphony, and there’s a community of musicians here to whom I feel very close. Travis [Andrews] and Andy [Meyerson] of The Living Earth Show are two of my best friends, and some of the most imaginative and dedicated musicians that I know.

“Contemporary music” covers a lot of ground. Where are you on it?

This is a great question, but it’s hard for me to answer. The idea of a tribe or a camp is not so much a relevant way to think about composers any more. You read about the “battle days,” from the ’50s to the ’80s, with these vicious, nasty rivalries between “downtown New York” and “uptown New York,” between the serialists and the minimalists. Now there’s so much going on, so many different composers from so many different backgrounds doing so many different things, that it’s almost impossible to point at one thing or another. Or to see me as part of a tribe.

It might be easier for people to try to link you to your dad.

I’m sure there’s a lot of that! [laughs] I’ve had some really reductive judgments about our similarities and differences. There are usually four sorts of diagnoses: You sound nothing like your dad, and that’s good; you sound nothing like your dad, and that’s bad; you sound like your dad, and that’s good; or, you sound like your dad, and that’s bad.

How often have you appeared on programs with your dad, as you will this Sunday?

Not that often, I can think of only three or four, at least that I’ve attended.

What will be special about an all-Adams program?

It gives the audience the opportunity to participate in acts of amateur psychoanalysis. [laughs] One aspect of being a composer that I’ve come to terms with is, once you’ve created a piece of music and it’s out in the world, it’s no longer yours, and you have to trust that whoever programs it and performs it is thinking about how it’s curated and presented. My String Quartet in Five Movements, which is going to be done on Sunday, may mean something different programmed alongside Haydn or Beethoven from what it will on Sunday, programmed alongside John’s string quartets [his First Quartet and Second Quartet].

Do you and your father share feedback about your compositions?

I think that we have a very open and honest conversation about art and about our work. It’s a privilege to be able to hear critical feedback from someone who is invested in you on personal and artistic levels.

Does communication come more easily because you’re similarly wired?

That’s hard to say. My sister and my mother [Deborah O’Grady] are also artists. We’re a family of artists, and therefore we’re a family of very sensitive people. It’s a delicate dance. One thing I’ve learned about the way John and I provide criticism or praise to one another is that it’s a kind of indirect action. It’s very rare that I tell him, I found this problematic or this excellent in one of his pieces, and very rare that he would do that with me. I find that if I want to get a message across to him, I’ll point him to a piece of music that I think is interesting. Listening or reading suggestions are a kind of gentle way of our articulating our sentiments about each other’s work.

Your dad was something of a pioneer in the use of electronics in music, even before he got to California in the ’70s. Have you two talked about the state of the electronic art?

Yeah. When he was experimenting, he was working with analog technology, Buchla synthesizers, even some of Moog’s instruments. I work primarily with digital technology, and I find the intersection between digitally created music and the fixity of digital sound to be really interesting when superimposed on or juxtaposed with acoustic instruments. Of course, I use a computer to compose, as well, not just for inputting notes but actually for the process of generating and transforming material.

Particular programs you’d recommend?

I use a program called Max/MSP, which is a platform for musical creation that’s very flexible. It allows you to engage with even nonmusical material, like lighting systems and other digital networks. I use Logic Pro, which is just a basic digital audio workstation. And I’ll use some other tools that my colleagues might develop, open source programs.

But no electronic elements in this Sunday’s concert.

No, these pieces are for a bunch of wood.

Electronics must have also affected your musical influences to a degree unavailable to your dad at your age.

Through the end of my teens and into my 20s, I became overwhelmed with this tidal wave of music. I had access to absolutely everything, and you can’t say that about John’s generation. His was a much more curated experience. What’s also changed is the way in which the music industry and music itself have responded to the economic realities of digital proliferation, where my experience is defined by moving from one geographical location or one century to another, within the space of three minutes. Not so much with my generation but with the generation that came after me, there’s a kind of democratization of experience.

Is that a good thing?

Not necessarily. There’s a burden, when I write a piece of music, to articulate exactly where all this information is coming from. The string quartet you’ll hear on Sunday is a perfect example of what I’m talking about, which is to say, it’s one of my more allusive pieces of music. There are needle-drops all throughout the piece: a little bit of Haydn, a little John Cage, a little James Blake, so many influences. But with the exception of one or two, none of them will be actually recognized, because they’re so fleeting and out of context. And there are influences from non-classical genres, like noise music or experimental, freely improvised music.

Along with the classical canon you were brought up in.

I do sometimes feel a personal burden, with every piece, to address the classical tradition and canon, or else I would be alienating the group of musicians from whence I came.

The elders who raised you and/or preceded you.

Yeah. Like my piano teacher, Chip Brimhall: I sometimes worry that if he were to hear a new piece of mine, he wouldn’t know that the heck I was thinking. And he’d think that all those hours of teaching me were going to waste. Sometimes I would like to be a composer free of that burden, but I think that that friction of needing to move forward, but also needing to address my roots, makes composing more interesting. I’ve learned to embrace the predicament more fully.

If you have to have a predicament, it should be interesting.

It’s a preexisting condition. [chuckles]

Where do you go next?

Tangibly, I’m excited about going to Australia, later this year, doing a piece with the Australian Chamber Orchestra. I have a premiere coming up with the CSO in May, a chamber violin concerto, with Esa-Pekka Salonen and Karen Gomyo, who’s a wonderful young violinist. I’m helping to produce a chamber opera I helped commission with the CSO, Savior, by Amy Beth Kirsten, in April.

You have referred to Doris Fukawa, who heads up Crowden, as your most important mentor. Will you be putting another generation of Adamses in Crowden?

Maybe. [laughs] We’re not quite there yet.