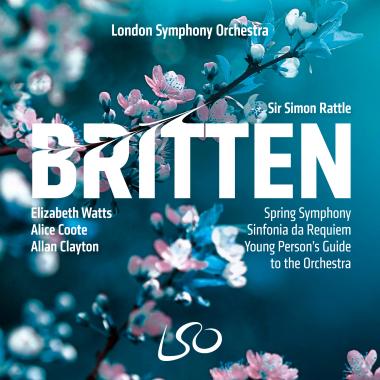

While Simon Rattle’s term as music director of the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) ended in 2023 (he is now conductor emeritus for life), recordings from his six years with the orchestra are still coming out on the LSO Live label. One recent release is likely to be among the best: a well-packed SACD survey of three works by Benjamin Britten, written during the composer’s astonishing artistic growth spurt in the 1940s.

Britten never wrote what you might call a traditional numbered symphony, but his Sinfonia da Requiem and Spring Symphony — along with the early Sinfonietta, the Simple Symphony, and the so-called Cello Symphony — more or less fill the gap. Sinfonia da Requiem is a one-movement work that can be separated into a three-part slow-fast-slow progression. The Spring Symphony is a symphony because Britten called it one — as Dmitri Shostakovich did for his Symphony No. 14, a de facto song cycle, and as Gustav Mahler did for Das Lied von der Erde (until his superstitious fear of the number nine made him withdraw the symphonic label).

Rattle recorded acres of off-the-beaten-path Britten when he was music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO). But this is his first shot at the Spring Symphony, a big-thinking work that sets a collection of English poems on the subject of spring, grouped into four sections that sort of resemble a four-movement symphony. Britten had some trouble getting the composition underway, with a lot on his plate after the success of his opera Peter Grimes, but he finally completed the Spring Symphony in 1949 in a delayed response to a commission from Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony.

Compared to Britten’s other works, the Spring Symphony is fairly uneven in inspiration, but its high points are memorable — such as the outbreak of “Spring, the sweet spring” from the adult chorus after the long winter introduction and the playful “The Driving Boy” from the boys’ chorus. The most moving music is the setting of the only modern poem in the collection, “A Summer Night” by W.H. Auden, Britten’s friend and sometime collaborator, with beautiful curling winds and a barely detectable ominous undercurrent. All but one of the other poems date from the 16th and 17th centuries.

In this recording, which has been sitting on the shelf since 2018, Rattle leads a large cast of three singers — soprano Elizabeth Watts, mezzo-soprano Alice Coote, and tenor Allan Clayton (ably undertaking the part written for Peter Pears) — and no less than four choruses — the London Symphony Chorus, Tiffin Boys’ Choir, Tiffin Girls’ School Choir, and Tiffin Children’s Chorus — with ample enthusiasm. If you have surround-sound equipment, there are some striking rear-channel effects to be heard on the SACD layer.

Rattle previously recorded Sinfonia da Requiem in 1984 with the CBSO; this new recording dates from 2019, and as far as interpretation is concerned, not much has changed in the 35 years separating the two recordings. The LSO strings are somewhat smoother and more refined, the explosions in the violent second section are just as vehement (though a bit muffled in sound), and there is more repose and revealed detail in the final meditation.

Usually, Britten’s own superb recordings of his music top the field, but in this work, Rattle matches the composer’s New Philharmonia Orchestra stereo recording from 1964 in brilliance and depth and almost in ferocity (Britten’s subdued earlier mono recording is thoroughly outclassed). While the Barbican Hall is notorious for its flat acoustics, hearing this performance in surround format (aided perhaps by some tweaking from the engineers) livens up the sound somewhat.

Rounding out the SACD is the wonderful Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra — or, if you will, Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell — which Rattle paces perfectly as the soloists and sections of the LSO provide plenty of instrumental fireworks. There are very few apparent differences between this and Rattle’s earlier recording with the CBSO, other than some balances in the ingenious closing fugue. The rap on Rattle in some quarters is that he hasn’t grown much as an interpreter over the decades, but if so, it’s all to the good in this piece. It’s fine the way it was and is.