2022 was the 150th anniversary of the great English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams’s birth, but did you hear about it in this country? I doubt it.

The Ralph Vaughan Williams Society’s tally of performances of the composer’s works in 2022 listed a plethora of concerts in England but just a paltry four in the U.S. and only one in Canada. The leading Southern California custodian of all things symphonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, completely ignored it. So did the San Francisco Symphony.

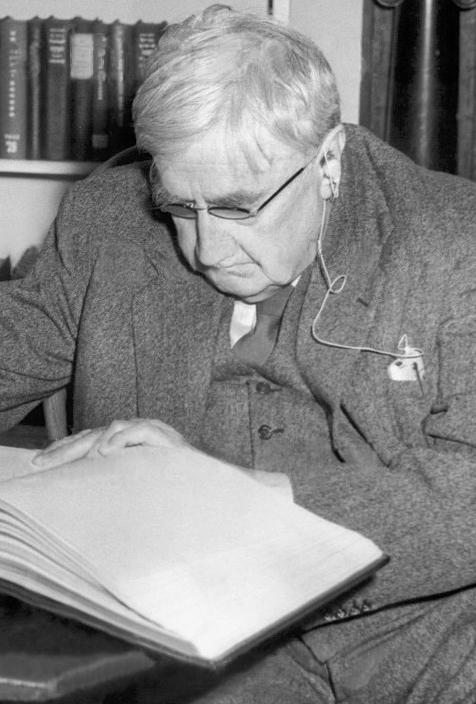

Which is shocking but not surprising because Vaughan Williams has long been unfairly tagged as a “provincial” composer whose music barely travels beyond the English Channel. Record collectors beg to differ; the shelves and streams are loaded with multiple recordings of the nine Vaughan Williams symphonies, plus concertos, operas, incidental music, choral and chamber works, songs, music for film and radio — you name it. There are many facets to Vaughan Williams that can and should travel, particularly the later works — the raging fires of the Fourth Symphony, the meditative eloquence of the Fifth, the apres-war desolation of the Epilogue of the Sixth, the morose, monumental soundscapes of Sinfonia antartica. But record collectors are not necessarily concertgoers — nor executives at concert organizations — and thus, the only way most have been able to get to know this composer’s music is through those spinning discs.

So hail Simone Young, the Australian conductor who brought Vaughan Williams’s rarely programmed Symphony No. 8 to her concerts with the LA Phil at Walt Disney Concert Hall over the weekend. It’s more than past time.

The Eighth Symphony was completed in 1955 when Vaughan Williams was 83. The dedicatee, John Barbirolli, gave the world premiere with his Hallé orchestra of Manchester in 1956 and then brought it to the LA Phil for the first time in 1959. It had not been played by the Phil since, according to a spokesperson. One wonders why not, for it’s a delightful piece, full of invention and whimsy.

The rejuvenated composer was in the middle of an unusually productive late Indian summer, searching for new sonorities while ignoring the Darmstadt serial crowd and other trends of the day. He was in a mischievous mood as he played around with symphonic form, doing a theme-and-variations bit for the opening movement and writing the Scherzo entirely for brass and winds and the soulful Cavatina solely for strings. In his notes for Barbirolli’s world-premiere recording, Vaughan Williams wrote that the spectacular Finale, labeled Toccata, “commandeers all the available hitting instruments which can make definite notes, including glockenspiel, celesta, xylophone, vibraphone, tubular bells, and tunable gongs” And he playfully added: “All the ’phones and ’spiels known to me.”

Young’s take on this unusual symphony was a license to speed whenever things got boisterous, really whipping up the razzmatazz in the coda while relaxing enough to let the cellos and basses sing out in the Cavatina. It was a more unbuttoned performance than those on records from British orchestras and also a much clearer one, with vividly transparent textures in this hall, especially in the strings. Maybe the symphony ought to be done in this extroverted way in order to catch the interest of American audiences. It certainly captured the Sunday afternoon crowd, judging from the exuberant ovation.

There was more English music from the program’s soloist, Gautier Capuçon, in the form of Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto. You can thank Jacqueline du Pré for really punching this somber and serious concerto into the repertoire via her famous recording with — there’s that name again — Barbirolli, and the work recently received an additional boost from its use in the controversial film Tár. Capuçon attacked the concerto with impeccable technique and unwaveringly firm tone quality, maintaining a tension that adhered tightly to the line. With the current unstable world situation in mind, he added Pablo Casals’s plea for peace, “Song of the Birds,” as a solo encore.

With English music as the theme, everything in the program fit together. Even the brief leadoff piece, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten, had honorary relevance as a moving homage to one of Britain’s greatest musicians. The cascading tintinnabulist patterns for strings and chimes sounded much lighter in texture in Young’s rendition here than in other performances. Nevertheless, taken as slowly as she dared, the music made its intended impact.