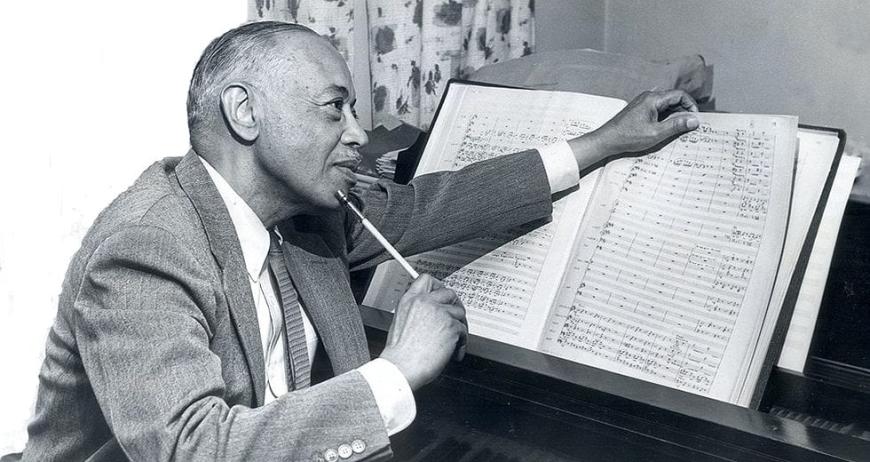

William Grant Still is the centerpiece of Black artistic exceptionalism in the classical performing arts in the 20th century before 1970.

As an African American male with classical music ambitions confronted by a debilitating structural racial animus, his legacy is a statement of an extraordinary transformative resilience. In our changed world, impacted by the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, and extremes of cultural-political divisions, the music of William Grant Still has found a permanence of acceptance and an organic sense of being not thought possible at the time of his birth.

As we celebrate Black History Month 2022 in concert halls nationwide, it is the music of William Grant Still which continues to center us in an appreciation of ideas about a Black lived experience.

Still’s legacy of a transformative resilience has acted as the bridge that connects us to an appreciation of an historical past and future about ideas of a Black cultural aesthetic in classical music. Importantly, it is also the bridge that has broken glass ceilings in the concert hall for Black composers, musicians, and conductors

The Jim Crow South of William Grant Still’s childhood was by design a restrictive state, a holding camp for maligned and displaced migrants whose plight overwhelmed a still-divided Union dawning into a new century, but yet still consumed by antebellum dissonances over structural racial hierarchy.

Still was one year old when Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court decision reinstitutionalized a structural white supremacy dismantled by the social utopianism of the assassinated President Lincoln with a re-enslavement through “separate-but-equal” segregation. Separate-but-equal mirrored, with its restrictive Black Codes, the convulsive repression of the 1830’s slave revolts.

The cultural and entertainment backdrop at the turn of the century found a White America infatuated with its antebellum era characterization of Blacks as comic yet conniving Jim Crows, uppity Zip Coons, neutered Mammies, and loyal Old Black Joes of minstrel shows.

This damning social and cultural narrative of Black inconsequentiality found push back in 1903 with the emergence of the black scholar and political progressive, W.E.B. Du Bois and his landmark book, The Souls of Black Folk, one of the first and most important investigations into the socioeconomic and psychological effects of racism. With this book, Du Bois established the critical paradigm of double consciousness, the individual and collective psychological dissonance that arises from perceiving oneself as “Negro” and as “American,” and recognizing that to be “Negro” is to be a foreigner and reviled as inferior by the larger society.

At the time of William Grant Still’s infancy, the vast repertoire and popularity of derogatory “coon songs” celebrated in blackface minstrel shows emphatically underscored the reality of Du Bois’ double consciousness paradigm in their irrefutable definition of “blackness” as incompatible with social parity and integration. However, a culturally significant and aspiring Black middle class, into which Still was born, resisted these demeaning stereotypes.

He was the son of two respected educators at Alabama A&M College. The death of Still’s father, when the child was three months old, and his mother’s remarriage to a Black man who was steeped in the love of music, and opera in particular, brought the boy into contact with a staple necessity of middle-class life. For their Victrola phonograph, Still’s stepfather purchased many operatic 78s and took the young Still to concerts. Still’s grandmother anchored his appreciation of the music of his people, Negro spirituals, which she sang to him. The world of the adolescent Still was a world that dreamed of uplift and found purpose in music.

During the first five years of Still’s life, lynching, a form of white supremacist racial control and terror instituted by Southern white men enraged at the Lincolnian idea of Black freedom, reached a crescendo. At the time, the idea of “racial uplift” embraced by Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B Wells, and Carter G. Woodson seemed incompatible with reality. Yet it is the paradigm of racial uplift that would become transformational in the life of William Grant Still.

Racial uplift was an ideology for racial transfiguration advocated by Du Bois and “The Talented Tenth” with the organizing principle that the Black people would be best led forward by an elite group of upper class, well-educated Black men and women already more closely assimilated to white American cultural and business norms.

The Talented Tenth idea advocated that the way forward for African Americans faced with the extraordinary racial animus of the Jim Crow South was to prove themselves, in the arts and professional fields, to be as accomplished and successful as their white counterparts.

Black excellence in these metrics would, in this ideological viewpoint, prove to white America that Blacks deserved greater respect and were interested in assimilation and integration into the larger social cultural and political American fabric.

Racial uplift through the classical performing arts, for African Americans of 1900–1918, was defined by artistic excellence in music as instrumentalists, singers, composers, educators, and artistic administrators.

The young Still learned to play the violin, cello, clarinet, and oboe. Encouraged by his mother, Still’s higher educational pursuits led him to Wilberforce University, when he was 16 years old. While at Wilberforce for a medical degree he quickly abandoned, he became proficient as a performer. He was a violinist in the Wilberforce University String Quartet and also performed in and wrote arrangements for the school band. He left Wilberforce in 1915 before graduating, taking odd musical jobs, and spending summer 1916 playing and arranging in W.C. Handy’s bands. A legacy gift from his father allowed him to matriculate at Oberlin Conservatory of Music in early 1917, where he studied composition with George Andrews. World War I interrupted his studies, when he decided to join the Navy. Between 1917–1918, in an American military segregated in duties by race, Still’s proficiency as a concert violinist elevated his status as an enlisted Negro to playing dinner music for white officers

After the war, Still moved to New York City in 1919 where he wrote to W.C. Handy for work and began a notable association with him.

From 1919 to early 1921, Still created important arrangements of Handy works, including the first orchestra arrangements of the landmark “St. Louis Blues” and “Beale Street Blues.” An artistic manager for the Handy Band, Still also worked at W.C. Handy’s music publishing company, Pace and Handy Music, the nation’s signature Black Tin Pan Alley music publishing business.

Leveraging his Black jazz world connections during the nascent Harlem Renaissance of 1920-21, Still’s talents as an arranger and instrumentalist came to the attention of Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle who were writing the score of the epochal 1921 musical, Shuffle Along, the first Broadway show in over a decade to be written, produced, and performed entirely by Black talent. Still provided uncredited arrangements and also played oboe in the show’s pit orchestra.

While performing in Shuffle Along, during its Boston tryout, Still studied composition for four months with George Whitfield Chadwick, who was director of the New England Conservatory. (He also studied for two years, 1923-25, with French avant garde composer Edgard Varese.)

Still left Pace and Handy Music in spring 1921 and followed its senior partner, Harry Pace, to assist in the creation and founding of Black Swan Records, a black record company created for the documentation of black artistic talent emerging out of the shadows of The Great Migration and the First World War.

In Harry Pace, Still was associating with a brilliant businessman, a quintessential leader of the the Talented Tenth, and a close friend of Du Bois.

From 1921–1923 Still was Black Swan Records’ music director, arranger, and artistic director and was responsible for hiring classically trained Black talent to work as studio musicians and recording artists. It is likely that Still is the uncredited violinist in recordings by the Black Swan Trio.

Still organized and conducted the Black Swan Symphony Orchestra, the label’s studio orchestra of Black musicians.

Still’s work for W.C. Handy and Harry Pace’s Black Swan Records lifted him, a protégé of racial uplift patronage, to notoriety at the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance. Yet it also exposed an extraordinary dissonance in ideology about race, culture, and Black music.

That is to say, Still’s embrace of Harry Pace and by extension DuBois’s ideology of “racial uplift,” of a Black elite trying to lift the status of the Black race through the internalization of a white cultural metric — accomplishment in classical music — in a segregated Jim Crow American society, might also be interpreted as racial denial.

Such a denial points to a broader internalization of colonial ideas about the inherent racial inferiority of “the colored race,” that was scientifically promulgated by the eugenics movement and had ramifications and through lines across American society at the time.

Eugenics combined with the institutionalization of “separate but equal” and technological advancement like the mass production of phonograph records and movies, meant that commercialized messaging of minstrel show-derived iconography was inescapable in the first two decades of the 20th century, and was backed by a pseudo-scientific consensus.

The glorification of the “lost cause” narrative of the Southern Confederacy produced D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915, enshrining a story about the necessity of white supremacy through a commercially successful movie, while sound recordings emphasized the plight of “the Negro Sisyphus” condemned to a perpetual status of “double consciousness.”

By contrast, Antonin Dvořák, during his residency at the American Conservatory of Music in New York in 1892–1895 had famously suggested that "In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.” The quote seems to invite moving beyond the internalized American struggle with racial identity and racial hierarchy.

Dvořák’s status as a revered leader in Western European music validated the exploration of African American and American Indian melodies in 19th and early 20th-century compositions by white men, giving a short-lived urgency to music by Arthur Falwell, Edward McDowell, and Charles Wakefield Cadman.

That urgency extended to Dvorak’s “Negro circle,” Harry Thackery Burleigh and the Black Broadway composer and violinist Will Marion Cook, to foster a “Negro aesthetic” in American classical music.

Embracing that aesthetic by incorporating “negro melodies” into Western European classical forms is central to the musical legacy of William Grant Still. Yet, the heralding and validation of the “Negro aesthetic” was a source of controversy for Still’s employers, Harry Pace and W.C. Handy.

For Handy, the aesthetic of the blues, work songs, and spirituals of Southern sharecroppers and manual laborers were the bedrock of a nativist black cultural identity,

By contrast, Harry Pace and other Black intellectual elites who migrated to northern cities believed that Southern Black folk music was unsophisticated if not primitive, and therefore anathema to the goal of high-class music and culture created for an evolved 20th-century “New Negro.”

The dissonance of ideology between these camps became a cultural tsunami. Handy’s embrace of an aesthetic of the blues and work songs relegated him to defending the lower class of Negro, antithetical to the racial uplift movement” of “The Talented Tenth.”

According to his grandson, Carlos Handy (who is a well-known physicist and chairs the physics department at Texas Southern University), the composer/publisher was highly erudite and well-spoken. Carlos has written about the glaring absence of his well-known grandfather from the operations and the board of Black Swan Records. In his telling:

“W.C. Handy was not invited. He was not perceived as being among the Talented Tenth, or a contributor to the uplifting of the race movement, as championed by the NAACP, as represented by Du Bois, of whom Pace was a perceived protégé. ... This social movement was led by highly university-educated Blacks (i.e. sociologists, Black university presidents, educators, scientists, lawyers, medical doctors, opera singers, etc). W.C. Handy was not one of them. He was the first composer to proudly recognize and embrace the Blues as an affirmation of Black musical creativity and achievement, a position antithetical to the Talented Tenth movement.”

Still’s leadership roles at Pace’s Black Swan Records raises the question: did he believe in prioritizing a higher class and higher culture for “an evolved Black America"?

Yet these dissonances also represented black sociological fault lines based on class, color and social standing as defining paradigms for the “cultural evolvement” of “The New Negro,” a concept codified in a 1925 book by Alain Locke.

The 1924–1929 blossoming of the New-Negro movement in the combined literary, art and performing arts world of The Harlem Renaissance embraced both ideologies which would announce not only the New Negro as a harbinger of racial uplift, Black exceptionalism, and Black pride but also a new “Negro Vogue.”

The preamble to this movement, musically, was the Black artistic excellence of that had already emerged before the end of World War I, in the blossoming careers of Florence Cole Talbert, R. Nathaniel Dett, Harry T Burleigh, Roland Hayes, C. Caroll Clark, Antoinette Garnes, and Lillian Evanti. Several had made sound recordings with George C Broome and his Broome Phonograph Record during early to mid-1919.

Black Canadian-born composer R. Nathaniel Dett along with composer and baritone Harry Thackery Burleigh were the leading early 20th-century champions to embrace and celebrate a “Negro aesthetic” sourced from 19th century slavery experience. Dett’s piano works “In the Bottoms” and The Magnolia Suite, along with Burleigh’s transcriptions of spirituals for concert voice and piano published in 1916 by the Italian firm of Ricordi set the stage for Still.

William Grant Still’s early orchestral work From the Land of Dreams (1925) was performed by the International Composers Guild. Darker America (1924–1925) won a publication prize from the Eastman School of Music and was performed by its orchestra conducted by Howard Hanson in 1926. Other noteworthy, Black-themed orchestral works of 1924–1927 included Levee Land (1925) From the Journal of The Wanderer (1925), From the Black Belt (1926), and La Guibalesse (1927) presaged Still’s arrival as classical music’s voice of the New Negro.

Still’s 1930 Pan African Movement thematic ballet, Sadjhi and The Afro-American Symphony were landmarks announcing the realization of Dvořák’s call to create an organic American cultural identity.

The composer continued to advance the “Negro aesthetic” in classical symphonic music in 1935 with Kaintuck, a symphonic concerto, and with his Symphony No. 2 (“Song of a New Race,” 1937). In 1936, Still conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic during its summer season at the Hollywood Bowl in the West Coast premiere of his Afro-American Symphony. He was the first Black man to conduct a major American orchestra. (And other Black classical musicians, like Florence Price were also making historic firsts at the time.) Yet, Still famously rejected the stereotyping of “the Negro composer” and “the Negro symphony”

In 1937 Still composed a narrative work for orchestra, chorus, and announcer, based on his experiences in Harlem, titled Lenox Avenue. The composition, consisting of 10 episodes and a finale, was commissioned by the Columbia Broadcasting System and was first conducted in a national broadcast by Howard Barlow on May 23, and repeated on October 17. Later, Still conducted it many times in concert.[3] The later ballet version was first presented by the Dance Theatre Group in Los Angeles in May 1938 with Norma Gould as the choreographer and Charles Teske as the lead dancer. In 1940, Artie Shaw recorded the movement “Blues” for Victor Records which further established Still’s reputation as a composer with a crossover appeal to both Black and white audiences.

Now revered as America’s ambassador of the “Negro symphony,” Still responded to his critical praise by saying “For me, there is no white music or Black music. There is only music by individual men that is important if it attempts to dignify all men, not just a particular race.” He continued, “As I see it, the music of the American Negro has resulted from the union of the religious songs you mentioned and the primitive songs of Africa. I believe that the use of a theme in blues idiom in a work of this sort for the purpose of welding it together is absolutely unique. And its rhythmic interest should prove to be equally as great as its melodic interest.” Still went on to contradict himself by saying “I harbor no delusions as to the triviality of [the] blues, the secular folk music of the American Negro.” It should be noted, however, that many modernist musicians held the attitude that mass entertainment music was trivial.

Yet again, the specter of divisive black sociological fault lines of class color and social standing were front in center in Still’s mind in the creation of his most famous composition, the Afro American Symphony.

In his journal, Still controversially wrote “I seek in the Afro American Symphony to portray not the higher type of colored American but the sons of the soil who still retain so much of the traits peculiar to the African forebearers ... who have not responded completely to the transforming effects of progress.”

Those sentiments echo an advertisement Harry Pace ran for Black Swan Records in 1922, making claims about a “higher class of music” and higher class of Black American versus a “lower class of music” and by extension a lower class Black American.

Both Still’s statement and Pace’s advertisement were contravened by what become the most popular and subversive aspect of the Harlem Renaissance’s “Negro Vogue,” the celebration and commercialization of “Afro-Jungleism.”

“Jungle music”, the exotic jazz music purveyed by Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Charlie Johnson’s Paradise Orchestra, Lloyd Scott’s and Luis Russell’s orchestras created an alluring mystique of a new African vogue with lurid sensual and savage rhythms paired with a subversive invitation to the cocaine and marijuana underworlds of “Minnie the Moocher.” They were the consummate 1920s and early ’30s hipster experience in a Manhattan in the throes of the Prohibition speakeasy world.

Bejeweled by scantily clad, light-skinned Black female dancers and a bevy of alluring chorus girls in extravagant floor show productions at The Cotton Club and Small’s Paradise, the new Negro vogue also became synonymous with an alluring exotic African mystique.

The so-called “Dark Continent,” a colonialist fantasy jungle with savage cannibals, primitive Zulu warriors, alluring native women, and imagined ceremonial orgies were fantasies of a white America still infatuated in a post Minstrel Show daydream.

On radio and records, numbers with titles like “Jungle Nights in Harlem,” “Black and Tan Fan Fantasy,” “Head Hunter’s Dream,” “Voodoo,” “Creole Love Call,” “Primitive,” “Back to The Jungle,” “Jojo Rhythm,” “Snake Eyes,” “Ghost of The Freaks,” “The Mooche,” “Zah Zu Zazz,” and “Minnie The Moocher” capitalized on the fad.

Max and David Fleischer of Fleischer Brothers Studios created Hollywood’s cartoon sensation of “Betty Boop,” which further commercialized an alluring and corrupting invitation to America’s youth, with its embedded showcase of Cab Calloway in veiled messaging about the dangerous and forbidden cocaine and marijuana underworlds in The Old Man of The Mountain and Minnie the Moocher.

Hollywood capitalized on the craze in a production number from Marlene Dietrich’s 1932 film, Blonde Venus with Dietrich sporting a blonde afro in a jungle scene with a cast of Black actors dressed as African natives, complete with warrior shields

The allure of the jungle also took Paris by storm with the ascent and deification of Josephine Baker and the Black doyenne of Paris café society, Ada “Bricktop” Smith. Baker’s exotic allure on stage and in film epitomized jungle mania in Europe.

While they created a sensation, and a financial behemoth for mafia bosses who underwrote this public invitation to forbidden sensual and carnal excitement, New Negro vogue and African vogue of exotica were also inspired by and creations of the rich artistic and literary genius of the Harlem Renaissance’s vibrant LGBTQ community.

The critical artistic leadership of the Harlem Renaissance were Black LGBTQ Americans. Monuments of Black LGBTQ Harlem creative genius can be found in the great murals of Aaron Douglass, the critical writing of Alain Locke, the poems and writings of Countee Cullen, Richard Nugent, Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, the artistry and popularity of singers Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, dancer Mabel Hampton, and popular cross-dressing lesbian entertainers like Gladys Bentley. Collectively, they signified a gay arts renaissance that presaged the cultural and political revolution that included Black transgenders four decades later in the wake of New York’s 1969 Stonewall Riots.

Before the paint on this canvas of artistic genius could dry, there was substantial push back from the leadership of the Racial Uplift movement. Du Bois famously dismissed the writings of this younger generation of black queer creatives as “filth.”

In particular, the writings of McKay, Nugent, Thurman, Cullen, and Fire¸ the short-lived magazine of black gay writers, were pilloried in the sermons of Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr., pastor of one of Harlem’s most prominent churches, the Abyssinian Baptist Church.

This was an era of extraordinary cultural flowering of a younger generation of Black creatives in a challenged coexistence with an upper-class Black elite whose ideas about morality and race aligned with the traditional fire and brimstone of the southern Black church brought forward into the post-Black Swan Records niche of “race records.” White-owned record companies actually recorded Black preachers, one of whom Reverend J.M. Gates was a charismatic minister wo sought to remind Blacks who had migrated to northern cities of their religious foundations. His recordings were foundational to Black social conservatism, and many recordings showcased him and in stirring sermons that weighed in on “the wicked morality” of wayward Black creatives and the lavish lifestyle that the “sedity [nouveau riche] Black elite” of Harlem’s Sugar Hill neighborhood had embraced.

That a Black gay aesthetic was at the epicenter of Harlem’s the New Negro movement was provocative. Even more provocative was that Carl Van Vechten, the white emissary and enabler of Black queer literary success dared to write an explosive novel describing the darker dimensions of domestic abuse and hyprocrisy in Harlem life titled Nigger Heaven. Collectively, the radical daring and success of black artistic queerness and Van Vechten’s expose acted as a pressure cooker that exploded upon the neatly appointed dinner tables of the brownstones of Sugar Hill’s elite families invested in respectability politics.

In contemporary academic Black and gender/sexuality studies circles, new scholarship has sought to call attention to a Black establishment suppression, if not complete whitewashing, of the LGBTQ artistic and literary foundations of the Harlem.

White artists appropriated Black-art trends, hoping to capitalize on their popularity. White symphonic composers followed William Grant Still’s Negro-vogue invitation with their own interpretations.

In Los Angeles, at the Hollywood Bowl Season 1932–1933, the Louisiana-born Albert Deano composed and staged a jungle-to-plantation-to-Negro spirituals extravaganza titled Negro Rhythms and Spirituals. The production employed a hundred dancers at the Philharmonic Auditorium. The movement titles were “Afric Rhythms,” “Afric Saturnalia,” “Plantation Impression,” “Cakewalk,” “River Jordan Spirituals,” and a finale showcasing the well-known Black Hollywood film star Clarence Muse. This pre-Busby Berkeley spectacle was conducted by Russian conductor Constantin Bakaleinikoff.

Carl Van Vechten acted as both emissary and door opener to white financial donors and white creatives including the well-known Jewish lesbian writer, Gertrude Stein. In 1934, Stein collaborated with composer Virgil Thompson to create Four Saints in Three Acts, which premiered with an all-Black cast. In 1935, George and Ira Gershwin produced their landmark “folk opera,” Porgy and Bess, on Broadway, followed in 1936 by Orson Welles’s Voodoo Macbeth, produced by his Mercury Theater, and set in 18th-century Haiti during the Black slave revolt.

Debate about cultural appropriation of black artistic creativity that advanced and catapulted the careers of white musicians of the 1920s and early Swing Era of 1935–1937 has been widely discussed and documented in modern scholarship.

Gershwin has been viewed in Black jazz and music historian circles as the supreme appropriator of Black musical culture beginning with his 1922 opera, Blue Monday, performed in blackface, then in 1924’s Rhapsody in Blue and then in his controversial “borrowing” of a Still melody that became his platinum hit “I Got Rhythm,” and culminating in Porgy and Bess.

In Ted Gioia’s A Subversive History of Music (2019) he reminds us “that the canonization of Gershwin’s jazzy classical works would have opened the door for an entire generation of Black jazz musicians to establish themselves as orchestral composers, but nothing of the sort took place”

Harlem’s leading stride pianist, harbored ambition as an orchestral composer. Johnson composed for and accompanied Blues singers Bessie Smith and Ida Cox, created scores for the all-Black Broadway revues Plantation Days (1922), Runnin’ Wild (1923), and Keep Shufflin’ in 1928 with his former piano student, Fats Waller. Johnson also recorded for Harry Pace’s Black Swan Records and became even more famous as the composer of two platinum hit songs of the 1920s, “Charleston” and “Runnin Wild.”

Johnson also composed Yamekraw, A Negro Rhapsody (1928) as a response to Rhapsody in Blue, Tone Poem in 1930, Harlem Symphony in 1932, and a symphonic portrait of W C Handy’s “St Louis Blues” in 1937. However, Johnson’s orchestral compositions never found the traction or critical reception that William Grant Still’s works on negro themes received.

Further to Gioia’s point, what ensued was a structural investment in the cultural appropriation of conveniences. White swing-band leaders such as Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey recognized the career value of hiring financially strapped Black arrangers and bandleaders as arrangers for their respected white bands. White swing of 1935–1936 was based on the 1934–1935 “swing sound” that Black bands had created. Due to racism and the challenges of performing in a Jim Crow America, many of these hot Black bands had folded by 1936.

Goodman, for example hired Fletcher Henderson as his chief arranger, a musician who had wowed the jazz world leading his orchestra at Connie’s Inn in the early 1930s, a band that was only rivaled by Ellington’s and Jimmie Lunceford’s bands. Henderson’s arrangements for Goodman, many of them charts he repurposed from his own orchestra, catapulted Goodman into the stratosphere, as the “King of Swing.”

Judith Still, William Grant Still’s daughter has written in no uncertain terms about appropriation, saying,

It is time for the racially defamatory opera, Porgy and Bess, to abdicate the stage. George Gershwin, said to be a friendly fellow, visited Harlem almost every night in the 1920s, where he and other white composers stole the music, songs, and dances of the prolific Afro-Americans and made millions from them.

The music of William Grant Still, W. C. Handy, and James Johnson was broadly taken over by Gershwin and, after all the thefts, composers of color were left with 'plenty of nothing.'”

Still relocated from Harlem to Los Angeles in 1934, was the recipient of a fellowship by The Guggenheim Foundation in 1934–1935 followed by a Rosenwald Fellowship in 1939. Before and during this time period, Still wrote a number of important chamber music works including Three Visions for Piano that includes his beloved “Summerland,” art songs, and works for solo instrument and piano such as Songs for Flute and Piano.

In Hollywood, Still worked as an arranger for three landmark film classics: Pennies from Heaven (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), and Stormy Weather (1943). For radio, Still wrote arrangements for Willard Robison’s Deep River Hour in the early 1930s and Paul Whiteman’s Old Gold Radio Show (1929–1930), and did arrangements for radio’s well known bandleader, Don Vorhees.

Still’s reputation in New York new-music circles led to an invitation from the 1939 New York World’s Fair to submit an entry in a competition for the entrance music that would greet attendees as they entered the City of Tomorrow exhibit. Still’s composition prevailed, after internal conflicts over enabling a Black composer to be so honored. Still’s composition, Rising Tide (sometimes referred to as Victory Tide), with lyrics by Albert Stillman, played on a constant loop inside the Perisphere for the multimedia exhibit Democracity (or The City of Tomorrow), a vision of urban life in the future with projected images, narration, and music.

The specter of “race” in an America of increasing indifference to racial animus and discrimination in the Depression years paired with increases in Southern lynchings of Black Americans greatly affected Still. The scourge of lynchings also affected Abel Meeropol, the Jewish American Communist who penned the 1937 anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit.” Performed by Billie Holliday and made famous at Manhattan’s hip music club for political progressives, Café Society, it cast a harsh light on the realities of the state of Black America with shared through lines to the racial terror that Jews in Germany and Austria were experiencing in 1937–1938.

In reaction, Still wrote one of his most provocative works in 1940: And They Lynched Him on a Tree.

Still’s Plainchant for America, for baritone and orchestra, received its West Coast premiere from the Los Angeles Philharmonic November 19-20, 1942, under the baton of John Barbirolli, with Jerome Hines as soloist.

Plainchant for America shared ideological bonds with Earl Robinson’s 1939 landmark work Ballad for Americans. At the time of its CBS radio premiere in 1939 and Victor recording in 1940, Ballad for Americans was a provocative and politically progressive vehicle that spoke to the urgency of respect for the African American contribution to the rich fabric of American history. It arrived concurrently with a nascent Civil Rights Movement that boldly announced itself on Easter Sunday, 1939, when Marian Anderson gave her legendary Lincoln Memorial concert.

“I, Too, Am America” is at the epicenter of its text, which Paul Robeson so poignantly sang in both the CBS Radio broadcast premiere and the 1940 recording. It is the phrase that is repeated over and over in the text as a call to social justice and full civil rights and integration into American society amid the racial inequities of opportunities for Black Americans in President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). This fervent advocacy of early civil rights leaders led to Executive Order 8802, issued by President Roosevelt, which prohibited discrimination in the nation’s defense industry.

The arrival of Ballad for Americans as a call to White America for self-reflection was a major vehicle for political messaging by the nation’s most vocal and respected champion of racial uplift and the dignity of the Black man, Paul Robeson. As a Robeson vehicle, Ballad shared bonds with the burgeoning American labor movement, which anchored itself in theme songs such as “Joe Hill” and “Freedom Train.”

“I Too Am America” as a thematic paradigm for racial equality, was also an important cornerstone of intellectual ideas about the place of the New Negro in critical poems penned during The Harlem Renaissance in 1926 by Langston Hughes in his “Dream Variations,” “I, Too, Sing America,” “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” and “I Dream a World.”

Still’s audacity to hope and to live a truth against all odds in his interracial marriage in 1939 to the Russian Jewish writer Verna Arvey (solemnized across the border, in Mexico), presaged the nation’s traumatic confrontation about race mixing and marriage which would be the basis for the 1967 Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia.

Still pressed forward tackling issues of race and black history in his 1939 opera, Troubled Island. Set in revolutionary Haiti of the 18th century, with a libretto by Langston Hughes, the difficulty that Still faced repeatedly in pitching Troubled Island for performance exposed the racism endemic in American performing arts and opera circles of the late ’30s and ’40s. Troubled Island was finally premiered in 1949 by The New York City Opera conducted and championed by its Hungarian Jewish exile emigré conductor, Laszlo Hallasz.

Although the institutions in the world of American music of this era prioritized men over women, women composers were significant champions of racial uplift through music. The brilliance of composers Florence Price and Margaret Bonds and the artistry of Marian Anderson and Dorothy Maynor represented a brilliant phoenix of artistic excellence that broke glass ceilings in concert halls where a racially restrictive color bar had reigned. Price’s arrangement of the spiritual “My Soul’s Been Anchored In The Lord” was recorded by Marian Anderson in the late 1930s for Victor, and remained core repertory for Anderson through the end of her career.

Bonds’s composition Sea Ghost won the prestigious national Wanamaker Foundation Prize in 1932. On June 15,1933, Bonds was the first Black pianist to perform with the Chicago Symphony during their Century of Progress Exhibition Series and returned in 1934 to premiere Florence Price’s Piano Concerto in D Minor. Moving to New York City in 1936, she befriended Langston Hughes and championed his poetry of the call to racial equity in settings for voice and piano. Bonds’s 1941 setting of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” would presage her important 1959 composition, Three Dream Portraits also based on Hughes’s poetry.

It was Still, however, as America’s “Negro composer,” who highlighted Black history through music and inspired Harlem-based jazz composers James P. Johnson and Duke Ellington.

Duke Ellington had already showcased evocative Negro themes in his compositions of the ’20s and ’30s such as “Creole Love Song,” “Black and Tan Fantasy,” “East Saint Louis Toodle-Oo,” “Birmingham Breakdown,” and “Song of The Cotton Field.” Ellington had also penned extended works that were ambitious in their intent to be viewed as jazz tone poems. These included his extended works beginning with “Mood Indigo,” “In My Solitude,” and “Creole Rhapsody Parts 1 and 2.

By the time of the culture shock of Pearl Harbor, Ellington had begun to write even more ambitious works, with his landmark “Negro Tone Parallel,” Black, Brown and Beige, which was performed at Carnegie Hall in 1943. Ellington’s admiration of Still’s leadership in highlighting the story of Black Americans in music was fulfilled in 1947 with The Deep South Suite, The Liberian Suite, and The Perfume Suite.

Black Brown and Beige is a metaphor for the prism of black skin color, imbued with its reference to the troubling and brutal history of slave rape. The culture of plantation rape amplified a structural differentiation of class and status given to generations of slaves who were mulatto or light-skinned scions of the slave master and a lesser status given to those who were dark-skinned with more African features. The ramifications of this class division in African American culture in the 20th and 21st centuries have been profound. Yet, Black Brown and Beige as portrayed by Ellington was a metaphor for 1930s–1940s racial pride and solidarity. Black Brown and Beige of this era symbolized a pride of cultural legacy that would anticipate the organizing principles of the African American holiday of Kwanzaa.

William Grant Still composed much important music after the era I am writing about, 1900–1942. But in this era, William Grant Still was the creative force who enabled a sea-change in ideas about the place of African American identity in classical music. He realized the dream that Dvořák spoke about by embracing and leading the call to create a unique American symphonic sound through the music of its native peoples. In the process, he helped forge a distinctly Black cultural identity in classical music, against the background of the Harlem Renaissance and the call for racial parity that it brought to the fore in American consciousness.

Indeed, through the corrected lens of the iconography of what “racial uplift” could entail in 1900, Still’s life and compositional legacy to America encapsulates the hope and dignity of Langston Hughes’s “I Dream a World.”