Lorena Maza, the director of El último sueño de Frida y Diego (The last dream of Frida and Diego), which closes out San Francisco Opera’s 100th season June 13–30, has a particular connection to the material. Maza’s best friend, whom she has known since they were 8 years old, is the grandson of artist Diego Rivera — the Diego of the opera’s title.

El último sueño, which premiered in San Diego in October 2022, takes place on Día de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead, in 1957. The artist Frida Kahlo has been dead for three years, and Rivera, her longtime partner, misses her and wants her to come back to the land of the living.

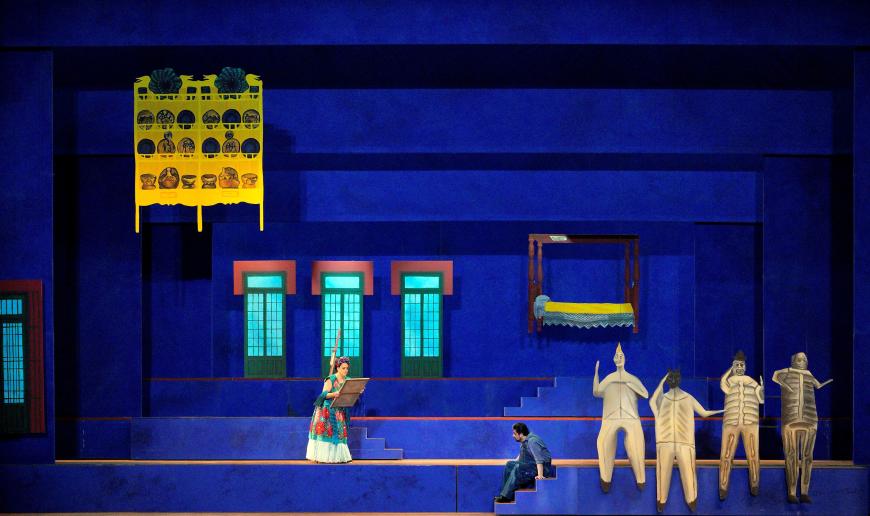

A team of designers from Mexico worked with Maza on the production, making sure to avoid folkloric cliches about the country, especially about the holiday that features in the opera.

“This Anglo-Saxon view of Día de los Muertos doesn’t correspond to the truth or reality at all. We don’t do parades. We don’t dress as Catrina. We just do altars, in our homes and in the cemeteries, to honor our dead and remember our dead,” Maza said on a video call from San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. “This is a story about forgiveness, surrender, and finding your identity through art. What we did is to bring our vision as contemporary Mexican artists to this story and avoid all this — I call it noise.”

El último sueño is the first opera by composer Gabriela Lena Frank, who has been interested in Kahlo since she was a child in Berkeley and her mother told her that the painter was, like her, short, dark, and creative. Both also dealt with physical challenges — Frank was born with hearing loss, and Kahlo had polio, which left her with a limp (a bus accident would later shatter her spine and pelvis).

Frank thought she would write the libretto herself, but her publisher quickly disabused her of that idea and told her they’d find a “real writer.”

That writer was Nilo Cruz, a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who, like Frank, had never written an opera. He had heard Frank’s music, and she had read his plays, and they both admired each other’s work. The two met in New York, set up by their agents. Since that meeting, the pair have created six works together, beginning with La centinela y la paloma (The keeper and the dove, 2011), a song cycle for soprano Dawn Upshaw; Santos (2013), an oratorio for the San Francisco Girls Chorus and Berkeley Symphony; Journey of the Shadow (2013), for the San Francisco Chamber Orchestra; the Conquest Requiem (2017), for the Houston Symphony; Las cinco lunas de Lorca (The five moons of Lorca), a digital short for Los Angeles Opera; and now El último sueño.

Cruz, on the phone from New Jersey, where he was directing his play Two Sisters and a Piano, said he got the idea for the opera when Frank played him something she’d written. “I was inspired to write the story of Frida and Diego not [as] a biopic but centered around the Day of the Dead,” he said. “So, the inspiration really came from her music more than anything.”

Cruz, who was born in Cuba, says he’s always been interested in Kahlo; he read a biography of her years ago and read more about her and Rivera while working on the opera. And he’s always been intrigued by the Day of the Dead, he says, having traveled to Mexico for the first time in his 20s to be there on the day.

Cruz was also inspired by learning that Rivera, when he was dying, said he wanted his ashes to be united with Kahlo’s — something that never happened. “Their relationship was almost like a hurricane, right?” Cruz said. “I mean, there were so many ups and downs, and it was so turbulent, but at the end of the day, they were soulmates. More than anything, I think they both adored each other.”

Cruz says he loves working with Frank, and her work reminds him of Ryuichi Sakamoto, the Japanese composer and pianist. “It was intriguing to me that she has this mixture of modern classical music and embracing her cultural background, which is something that I do too in my work,” Cruz said. “I felt what she was doing with music is what I was doing in the theater.”

Maza says Frank and Cruz, neither of whom are Mexican, have created a unique universe that tells a unique story — one that doesn’t just belong to Mexico. “Nilo wrote a beautiful, beautiful text,” the director said. “I have read everything he has written for theater, and I consider him an amazing playwright.”

Maza revealed that the Mexican creative team did some dramaturgical work rooting out errors, such as when the operatic Rivera says, “God exists.”

“Diego was an atheist,” Maza said. “He would never say that. We changed it to ‘Mictlan exists,’ which is the Aztec underworld.

“There is this amazing part when we do a tableau vivant, and the mural comes to life, and Frida for the first time is back on earth. She’s stopped feeling pain, and she dances around to beautiful music, very melodic,” Maza said. “But she has — what are those things — castanets? And we said, ‘Listen, Gaby. Castanets are not Mexican at all. They are very Spanish, and I’m very sure Frida would have hated them.’”

Daniela Mack, who plays Kahlo, was born in Argentina, and she says Maza’s knowledge has been invaluable. “She, along with her designers, have created this world where, yes, we’re telling the story of Frida and Diego, but we’re also celebrating Mexican culture,” Mack said.

Like Cruz, Mack did research on the artists, including reading Kahlo’s diary. What struck her most, and what she wants to convey, is Kahlo’s strength and force of will in the face of the intense suffering she experience for most of her life. She calls it a privilege to portray Kahlo and says she is happy to be in the first SF Opera production sung in Spanish.

Working on El último sueño is different in other ways, Mack says. Along with Maza and her design team, there is also a Mexican conductor — Roberto Kalb — along with Mexican singers and pianists. “There are a lot of people to whom we can turn for guidance in this process,” Mack said. “That’s something that is kind of rare, to be honest, to turn around and see primarily people of color in the rehearsal room and people who really take ownership of the story because it belongs to them in a certain sense.”

Maza says she loved working with a living composer and librettist and that directing this project was a joy. And the Spanish language made it even more beautiful, she adds. “In California, it makes so much sense, and in San Diego, many, many, many people in the audience were there [at San Diego Opera] for the first time in their lives because it was in Spanish and they could understand it,” she said. “They could see themselves there, represented, so they could say, ‘OK, opera is also for me.’”

Maza says she’s enjoyed being in San Francisco and thinking about how Kahlo and Rivera, who got married for the second time at San Francisco City Hall, right across from the War Memorial, passed by where the opera will be performed.

San Francisco was an important place for the couple, Maza says, with Rivera painting his first American mural here. Kahlo, meanwhile, identified herself as a housewife on an immigration form when she first came to the city, but when she left, she wrote that she was an artist.

“When she left, she was a painter,” Maza said. “Here she recognized truly who she was. It was a very transformative time for both of them.”