People called her “the high priestess of soul” or a jazz singer, but Nina Simone said there was more folk and blues in her music than jazz. Dave Marsh, the music critic, suggested calling her a “freedom singer.” Bob Dylan said she was an artist he loved and admired, and that the fact of her recording his songs validated everything he was doing. Along with Dylan’s work, she played renditions of songs by the Animals, Leonard Cohen, and Jacque Brel. Kanye West has sampled her in his songs. Barack Obama had her song “Sinnerman” on his workout playlist. Writers Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and Langston Hughes were her close friends. She trained to be a classical pianist and Bach was her favorite composer because of his technical perfection.

Raised in Tryon, North Carolina by a mother who was a Methodist preacher and a father who did whatever work he could get during the Depression, including barber, handyman, and delivery driver, she had never been in a bar till she played at the Midtown Bar & Grill in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and when asked what she wanted to drink, she asked for a glass of milk. When Vernon Jordan, the head of the Urban League, asked her why she wasn’t more active in the Civil Rights Movement, she responded, “I am civil rights, motherfucker.”

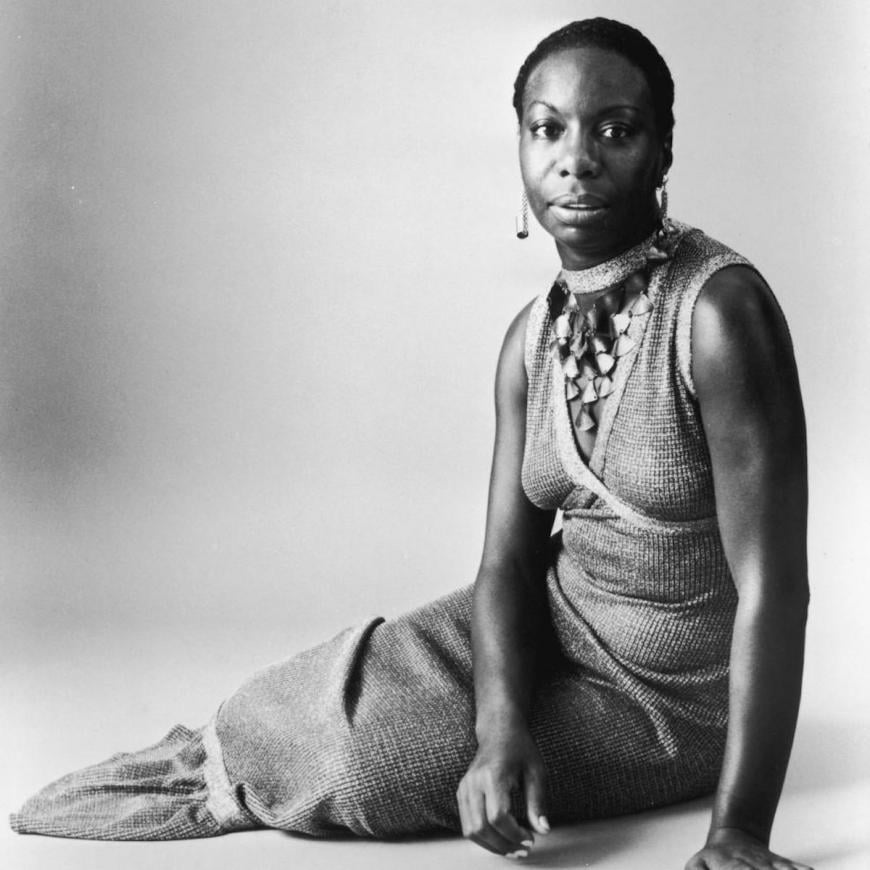

Simone (1933 – 2003) was uncategorizable and singular, making any song she sang her own. Born Eunice Waymon, she trained to be a classical pianist and studied for a year at Juilliard but wasn’t accepted to Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia, a decision many attributed to racism. Simone was an activist during the civil rights movement, famously saying that an artist’s duty was to reflect the times. She left the United States and moved to Liberia, then to Switzerland, before finally settling in the south of France.

“Why? (The King of Love is Dead)”

Nina Simone and her band performed this song at the Westbury Music Festival on Long Island, New York, in 1968 three days after Martin Luther King was killed. They had just learned the song, which their bass player Gene Taylor wrote in response to King’s murder, and the song is enraged, heart wrenching, and catchy. Simone’s voice soars as she sings, “Turn the other cheek he’d plead/ Love thy neighbor was his creed/ Pain humiliation death he did not dread/ With his Bible by his side/ From his foes he did not hide/ It’s hard to think that this great man is dead.” The song appears on Simone’s 1968 live album, ’Nuff Said.

“To Be Young, Gifted, and Black”

Simone and her friend Lorraine Hansberry bonded over civil rights and radical politics. Before she died at 34 of cancer, Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun, was talking to a group of student essay winners and she told them, “I wanted to be able to come here and speak with you on this occasion because you are young, gifted, and black.”

Simone said the words stuck in her head and she sat at the piano and wrote the song, which she said felt like a gift from the playwright. Her bandleader wrote the words and she told him to keep it simple, something that “will make black children all over the world feel good about themselves, forever.” The song, which became a sort of Civil Rights anthem was released on the 1970 record Black Gold.

“Mississippi Goddam”

Simone wrote this song in response to the bombing of a Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama that killed four girls and to the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi. Reportedly she sat down and wrote the song, which opens “Alabama’s gotten me so upset / Tennessee made me lose my rest / And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam,” in under an hour, and said it felt like firing bullets back at the Ku Klux Klan members who planted the dynamite in the church. Dick Gregory commented, “We all wanted to say it. She said it. Mississippi, God DAMN.” The song, with intense, stinging lyrics and an uptempo beat, became a famous protest song, and one that some radio stations would send back, broken in two. It was released on the 1964 album Nina Simone in Concert.

“I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to be Free”

This song was an instrumental, written by jazz pianist Billy Taylor, with lyrics added later by Dick Dallas. Simone recorded it for her 1967 album Silk and Soul, and with lyrics like I wish I knew how it would feel to be free/ I wish I could break all the chains holding me/ I wish I could say all the things that I should say and I wish you could know/ What it means to be me/ Then you’d see and agree/ That every man should be free, along with Simone’s artistry, it became another song important to the Civil Rights Movement.

“Backlash Blues”

This song, included on the 1967 album Nina Simone Sings the Blues, is from a protest poem by Simone’s friend Langston Hughes. The music she wrote is more straight up blues than many of her songs, but the lyrics including, “You give me second class houses/ And second class schools/ Do you think all colored folks/ Are just second class fools?” are stirring and politically focused like many of her other songs.

I Put a Spell on You: The Autobiography of Nina Simone

In Simone’s 1991 autobiography, done with Stephen Cleary, she writes “Everything that happened to me as a child involved music.” She began piano lessons in her small North Carolina town walking two miles and crossing the railroad tracks to study with her first piano teacher, Muriel Massinovitch. At her first piano recital when she was 11, her parents were moved from their seats in the front row, and she refused to play until they were back in those seats and could see her hands as she played.

Liz Garbus’s documentary, which opened at Sundance in 2015, goes through some the broad shapes of Simone’s life from studying to be a concert pianist to playing in bars to touring the world to working in the Civil Rights movement, and her moves to Liberia, Switzerland and the South of France. Her longtime guitarist, Al Schackman, is interviewed, along with her daughter, Lisa Simone Kelly, the executive producer of the film, and Lisa’s father, Andrew Stroud.

The archival footage of Simone is stunning, and her struggles, particularly during the latter part of her life are touched on, sometimes to the point of overshadowing her incredible contributions to music, but it made me think of something in Anna Malaika Tubbs’s recent book, The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation.

In it, Tubbs writes about Malcolm X’s mother, Louise Little, who spent years in a mental institution, and suggests part of the reason she was there was being a Black woman trying to tell the truth. Attallah Shabbazz, daughter of Malcolm X, and a family friend, says about Simone in the documentary, “She was not at odds with the time, the times were at odds with her.”