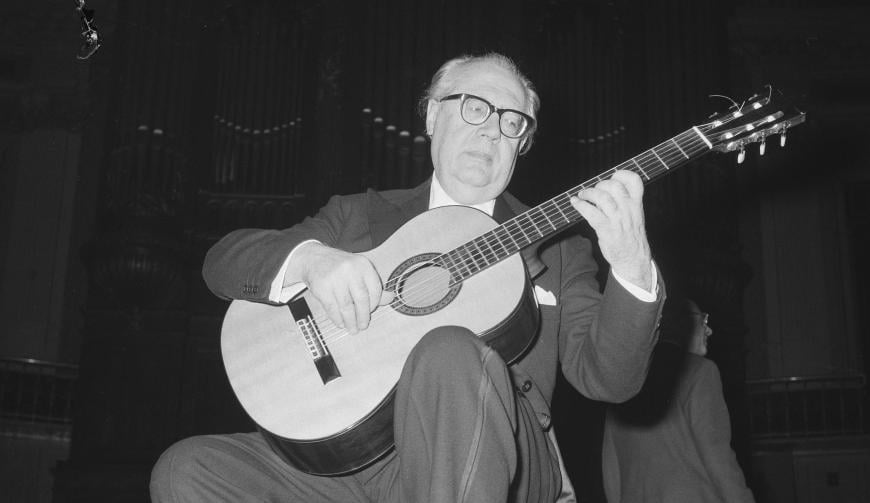

Andrés Segovia (1893–1987) was the most influential classical guitarist of the 20th century and remains important to music lovers of the 21st. Just consider his success in having the guitar accepted as a solo instrument in concert halls, the beautiful repertoire written for him, the transcriptions he made of music written for other instruments, and his fruitful campaign to have the guitar taught at the world’s music schools.

Andrés Segovia: 1927–1939 Recordings, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2

Segovia’s first recordings were made for His Master’s Voice/Victor Red Seal, the most prestigious and technically advanced recording label of the early 20th century. Recording grew more sophisticated through the 1920s, but the technology of the time demanded recordings be made in one take, so musicians had to be at their very best. Segovia had been giving professional recitals since 1909, when he was 16 years old, so he was more than ready to take advantage of the opportunity.

The repertoire he recorded included transcriptions of works by J.S. Bach and earlier Baroque composers, as well as original compositions by Fernando Sor, Francisco Tárrega, Federico Moreno Torroba, Joaquín Turina, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and Manuel Ponce. Listeners who value historically informed performances might not enjoy Segovia’s freer interpretations of Baroque music but will find his performances of Romantic and early modern composers to be a revelation. These recordings offer a portal to a lost world, and Segovia’s sound, with its rich tonal palette, sensuous vibrato, idiosyncratic rubato, varied articulation, and individualistic approach, is the essence of late Romanticism. This all is enhanced by the sound of gut strings, which Segovia, like all guitarists used, before the advent of nylon strings after World War II.

Equally notable, Segovia plays a historic Ramírez guitar (made by Santos Hernández), gifted to the Segovia in 1913 on the occasion of his Madrid debut and currently on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Andrés Segovia: The American Decca Recordings (six discs)

The Deutsche Grammophon 2009 rerelease of Segovia’s recordings for Decca from the years 1944–1954 show the guitarist in his absolute prime, tackling everything from Handel, Haydn, and Girolamo Frescobaldi through Felix Mendelssohn, César Franck, and Manuel de Falla. The heart of the project is the beautiful music composed for Segovia, an impressive list with pieces by Torroba, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ponce, Alexandre Tansman, Joaquín Rodrigo, Joan Manén, and Heitor Villa-Lobos. Beginning with Julian Bream and John Williams, every important guitarist has been deeply influenced by these recordings. Sadly, the DG remasters with the original order and 1950s graphic design are no longer easily available, but Naxos has released a six-volume series titled Andrés Segovia: 1950s American Recordings, which includes all the same recordings, though in a different format.

The Segovia Collection, Vol. 1

1959 was the 50th anniversary of Segovia’s debut at the Centro Artístico, Granada. To celebrate, he presented Segovia Golden Jubilee, a full three discs on Brunswick, whose highlight is the premiere recording of the Fantasía para un gentilhombre by Rodrigo, with the Symphony of the Air conducted by Enrique Jordá. The composer’s wife, Victoria Kamhi de Rodrigo, gives a short account of the world-premiere performance at the San Francisco War Memorial Opera House in her book Hand in Hand With Joaquín Rodrigo:

“We left for San Francisco the 27th of February 1958, and on the 6th, 7th, and 8th of March, Segovia presented the Fantasía para un gentilhombre in the great opera house of that city. At the San Francisco airport, Andrés Segovia was waiting for us, with Enrique Jordá and his wife, Audrey, and some reporters. They took us to the Francis Drake Hotel, where we had a short time to rest. The rehearsal began at once, for only a few days remained before the premiere. Then followed the rounds of the press, interviews, parties, dinners with the artists and the critics. Nothing was omitted that would characterize this premiere as a great event. And the success was complete, unanimous, enthusiastic. In all three of the successive concerts, the audiences who filled the hall applauded the soloist and the composer with fervor. During the intermissions people surrounded us, with radiant faces, to congratulate us, to request an autograph, a photo. It was thrilling!”

This DG remaster also has Ponce’s Concierto del Sur, recorded on the same May 1958 sessions as the Fantasía.

Segovia at Los Olivos

Segovia reached his artistic peak in his 60s and continued to perform to great acclaim for 30 more years. Though age inevitably diminished his physical ability, the beauty of his sound and the depth of his musicality remained. Segovia at Los Olivos, a documentary film by Christopher Nupen, released in 1967 when Segovia was 74 years old, is the finest record of Segovia in old age and features both fascinating conversation and exquisite playing.

Segovia’s last album, Reveries, recorded in 1977 when he was 84 years old, is an expensive collector’s item. One of his last performances was given in 1987 at age 94. In the Chicago Tribune, Howard Reich wrote an illustrative review:

At 94, the grand old maestro can still bring an audience to its feet. Granted, the standing ovation given guitarist Andrés Segovia Sunday afternoon in Orchestra Hall was as much a tribute to his long and brilliant career as to the exquisite concert he had just concluded. But surely the crowd, so large that it had to be accommodated with stage seating, had been touched by some of the most delicate, carefully wrought guitar playing one could hope to hear. Though he walked onto the stage slowly, leaning on a cane, Segovia had only to sound the opening theme of Frescobaldi’s Aria con Variazioni to prove his art is still very much intact. The trademark singing tone, gentlemanly tempo, and elegant melodic embellishments remain the envy of guitarists half his age.

But only Segovia can create so many colors and moods while playing, barely above a whisper. Like many another old master, his is an economical art, with every gesture fashioned for maximum impact. At his best, the Spanish guitarist seemed to defy the limitations of his instrument, as he did in Fernando Sor’s Andante and Minuet. One would hardly have guessed that its melodies had been plucked on strings, so seamlessly did Segovia spin one silken phrase after another.”

A little over two months later, Segovia died.