Given the number of barriers she has broken during her long and impressive career, one wouldn’t think there were any more firsts available for Marin Alsop. But that would be incorrect. Later this month, the pioneering conductor will make another major debut, this time at the Metropolitan Opera.

Beginning April 23, Alsop will be conducting the Met’s first-ever production of El Niño, the opera-oratorio by her close friend John Adams.

“I’m a person who makes lifelong commitments,” she noted, and this production is the culmination of a decades-long mutually respectful relationship. In a nice bit of synchronicity, Naxos, on April 5, is releasing a CD of Alsop conducting three Adams works with the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSO), where she serves as chief conductor.

“I got to know him and fall in love with him as a human being when I was music director of the Cabrillo Festival for 25 years,” she recalled about Adams. “I did a lot of his music there. The new CD includes a world-premiere recording of a piece he wrote for me when I finished my run at the festival. That helps make the recording feel very personal to me.”

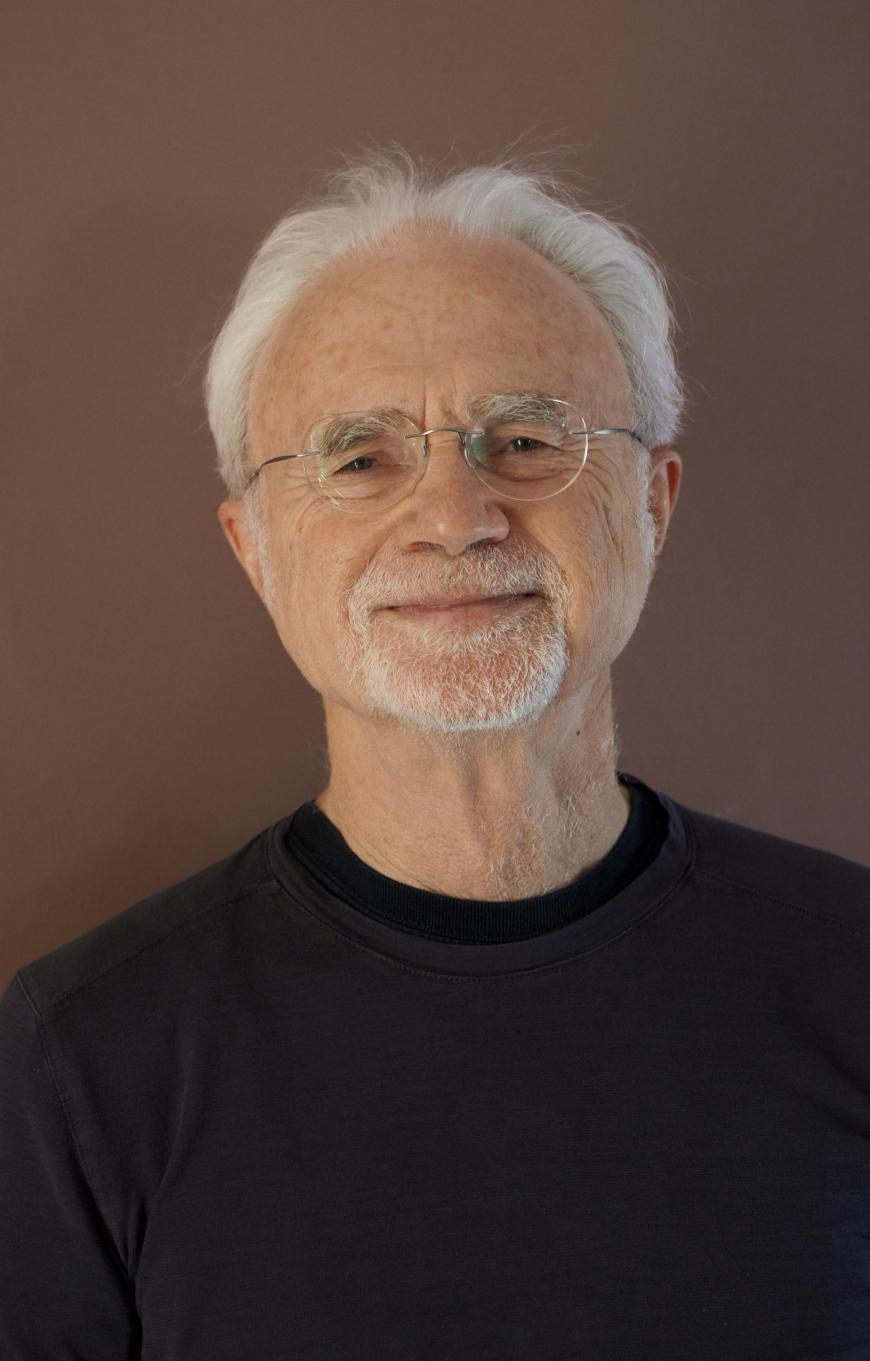

A major interpreter of many American composers, including Adams and Leonard Bernstein, Alsop, 67, is perhaps best known as the first woman to be named music director of a major American orchestra. She held that position with the Baltimore Symphony from 2007 to 2021. Her numerous awards and honors include a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Currently, she splits her time between the Vienna RSO; the Polish National Radio Symphony, where she is artistic director and chief conductor; the Philharmonia in London, where she is principal guest conductor; and the Ravinia Festival (the summer home of the Chicago Symphony), where she is chief conductor. In addition, she was recently named principal guest conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra, effective this fall.

During a recent visit to the Monterey-Carmel area to see friends, Alsop took time to talk to SF Classical Voice about her approach to music and life and her relationship with Adams.

Has conducting an opera at the Met been a longtime goal of yours?

Making my debuts at the Met and at the Berlin Phil, which I will next year, do feel like some kind of markers. But the thing I love about the Met experience is I will be able to be in my hometown for a couple of months. New York is where I grew up. I spent many evenings at the Met, watching productions. I look forward to working with artists at an incredibly high level. I’m also happy I won’t have to be traveling every week for a couple of months.

On the subject of career moves, the Los Angeles Philharmonic is in need of a new music director. Would you be interested in that position?

I haven’t been to L.A. in a few years. I’d love to do a weekend [as a guest conductor] and see how it goes. You never say never, but I try to live my life being present in whatever I’m doing. I’m full up at the moment — and enjoying it tremendously.

I have no idea what the future will bring. But it’s great to wake up every day and be grateful for one’s profession.

I’m curious to learn your reaction to Maestro, Bradley Cooper’s film about Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein, of course, mentored you during the final few years of his life.

Bradley was in touch with me during the filming process. I thought that for what it was, he did a great job. It was a project of great commitment and passion for Bradley. I really respect that. But for me, it was too Hollywood — too narrow a view of Lenny. It was clearly about his marriage. I never met his wife; she died in the ’70s, before I knew him. But I’m close with the kids.

Was the guy you saw on the screen recognizable to you?

That’s a difficult question. He certainly was familiar to me. Bradley captured a lot of his mannerisms amazingly well. But it was much too narrow a portrait of the person I knew. From my perspective, it was seeing one dimension of someone you knew in a multidimensional way. So for me, it was familiar but incomplete.

Let’s talk more about John Adams. What initially drew you to his music?

When I was in my late teens and early 20s, I played violin with both the Steve Reich Ensemble and the Philip Glass Ensemble. So I was engaged in the minimalist movement during its early days. One of the first pieces [by Adams] I started to do as part of my conducting repertoire was The Chairman Dances [the composer’s offshoot to his opera Nixon in China].

I was drawn to John’s music partly because of that minimalist language. But I also love his sense of structure and his sense of humor. His dance grooves are very appealing to me; they come across to me as quintessentially American.

El Niño premiered in 2000 and sounds amazingly fresh today. Why do you think so much of Adams’s music has proven to have staying power?

Whether it’s an opera, a symphony, or a tone poem, his music has drive. It has beautiful architecture. I love the way he uses metric modulation. That has always appealed to me. His orchestrations are always fascinating as well. On the new CD, Fearful Symmetries and City Noir have completely different orchestral sounds.

When you play John’s music — or, for that matter, music of any living composer — do you get him on the phone and ply him with questions about the piece?

For me, that’s typical. As a conductor, I’m trying to be the messenger for a composer. If he, she, or they are alive, being able to talk to them is a treasure trove. John and I had a long Zoom call about El Niño a few weeks ago when I was in Vienna. It was great to hear about the gestation of the piece. There’s also the added advantage of having John as a conducting colleague. He can offer his tips of what works and doesn’t work conducting-wise. He’s extremely generous with his knowledge and his time.

How much interpretative leeway does Adams’s music give you?

Highly rhythmic music that’s locked into a pulse doesn’t give you the typical kind of interpretative leeway than you have conducting, say, a Mahler symphony, where every four bars can be interpreted differently. But it gives you something else — something that has to do with internal pulse and orchestral color. For me, it’s super important to take the piece to its culmination so it pays off for the listener.

What does that entail?

What is the arrival point of this piece? What’s the moral of the story? Every piece has a narrative of some kind. It’s my responsibility to not just convey that narrative but also draw out the moral of that narrative. I want people to leave feeling differently than when they arrived.

Is El Niño at the Met going to be fully staged?

Yes. I’ve spoken to the director, Lileana Blain-Cruz, a couple of times. She seems really cool — engaged, committed, fascinating. Both being women, we talked a lot about the female role in the Nativity story. There are lots of layers she is looking to unpack, including the concept of forced migration when Mary and Joseph are forced out of their homes. That’s so topical for the world we’re living in today.

The production is going to be really vibrant, with lots of primary colors. There will also be puppets. It’s going to have an arc, a storyline that will carry it to a new level.

How did it come about that you were hired by the Met? How do they decide who conducts which operas?

You’re asking the wrong person! But I feel confident that John recommended me.

You made a comment to The New York Times a few years ago about how people in our society interpret gesture very differently depending on whether it’s coming from a man or a woman. A delicate movement from a woman can be seen as weakness, where an identical one from a man can be seen as sensitivity. Has that knowledge affected your podium style? On the whole, your body language while conducting is pretty forceful.

It’s a really interesting topic. Conducting is all about body language, so we have to be constantly aware of it. I work a lot with my students, particularly my female students, on trying to degenderize gesture. I’ve worked on that a lot with my own gestures. If they seem strong, that may be partly a reaction to wanting to make sure it’s not interpreted in a certain way.

First impressions of people you meet are formed very quickly. I’m always telling my students, “You need to be thinking about the music before you step on the podium. Be completely engaged. That’s what you need to convey. That’s what everyone needs to see from you.”

Finally, a political question. We are going through a period of intense backlash to much of the progress that has been made in recent decades, including with women’s rights. What can you as an artist do in reaction to this trend?

I’ve lived through many periods of progress and regress. It’s sort of a pendulum. For me, now is the time to be even more vigilant about supporting women and other underrepresented people in the field. That’s my passion. That’s my commitment. I do it in every way possible.

I started a fellowship for women conductors in 2002. They are doing incredibly well. I’m so proud of them. I’m trying to make a difference in the way that I can, which is all that any of us can do. That, and to speak up. Speaking up gets me into hot water at times, but I can sleep at night. I’m trying to be more circumspect in my mature years.

Are there orchestras that would rather you didn’t speak up?

Every orchestra!