When the creators of the Broadway show Martin Short: Fame Becomes Me decided to write a song called “A Big Black Lady Stops the Show,” they thought of Capathia Jenkins (pronounced Kah-pay-thee-yuh). When Ben Brantley of The New York Times reviewed the show, he called her nothing less than a “Dea ex machina.” A graduate of the illustrious “Fame” school, also known as LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performance, Jenkins has several other roles on Broadway to her credit, including in Tony winning shows like Caroline Or Change and Newsies.

Her off-Broadway performance as the first African-American Oscar winner in (Mis)understanding Mammy: The Hattie McDaniel Story won critical praise, as have her recordings and performances at Joe’s Pub with guitarist-composer Louis Rosen. In recent years her concert performances with symphonies have prompted more time on the road, nothing new for the performer who toured nationally in Dreamgirls as Effie White, singing the show’s biggest hit, “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going.”

The vivacious Brooklyn native will travel west this summer holiday to join in the San Francisco Symphony’s Independence Day celebrations, singing a program featuring Gershwin at Symphony Hall on July 3, and in a fireworks extravaganza concert at Shoreline Amphitheater on July 4.

Can you talk about your early influences? Especially some of the luminaries in children’s choruses in New York, like Walter Turnbull and John Motley. Did you sing in the All-City Choir?

I sang in the All-City High School Chorus. That’s where I worked with John Motley, I think in 10th grade. And with Walter Turnbull there was a Girls Choir of Harlem, and I did that maybe 10th or 11th grade as well.

Was it a great experience?

Absolutely. At that time, I was so excited to be singing, singing, singing! But with those two men I started to learn how to maintain your voice, what’s required, the technical things you’ll need as a professional singer, things that will be your bread and butter. They were both strong disciplinarians, very structured. They taught us how to warm up your voice, to be quiet before you’re going to sing and take the stage. As a kid you’re singing in church, you’re singing in school, but with them I learned it is a very serious thing.

Some of the things I learned from them are still the way I work today. A lot of my work has been on Broadway, where it’s sort of a team effort. You show up and meet the cast and the director; it’s sort of like the first day of school and everybody is in it together. But particularly the symphony work is a very solitary thing. I’m at home in my office, learning my music, drilling it, making sure I’m off book, that it’s inside of me before I get with the orchestra. I take it very seriously. It’s my time to work. I wake up, have my morning, and go into my office. I stop and have lunch, and then go back in to work. The way they taught us as kids to be specific, dedicated, and focused, I still use those skills today. I learned a lot from them.

You trained classically until you were 18. A lot of great classical artists came out of that high school. Why did you feel so clear that you didn’t want to pursue an operatic career?

Once I got to 11th grade, heading into my senior year, my voice teachers were pushing the idea of Juilliard and a classical career. I grew up in the church, so I loved the freedom of gospel music, I also lived with older siblings, so our house was filled with Motown, and Earth, Wind & Fire, and Gladys Knight; there was this soulful thing happening as well. I knew I didn’t want to have a career in classical music. I knew in my gut. But in retrospect, when I think about my classical training, it’s the best thing that could have happened to me. Particularly in this time in my career, I know how valuable it was to learn how to mechanically, technically, sing. Doing eight shows a week on Broadway is a grind; traveling, getting off a plane and having to hit the ground running, you have to know what your instrument can do. Classical training taught me all of that. I can listen to opera singers and absolutely, mouth open in awe at the sound they are able to produce. I know how they do it technically, but I wasn’t really lit up on the inside, singing arias and doing that whole thing.

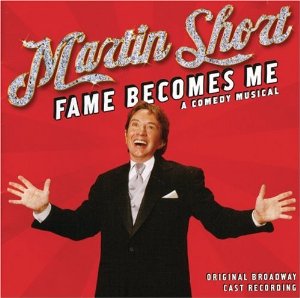

Martin Short is one of those people, I laugh just thinking about him. How do you get anything done working with him?

That’s the truth. I don’t know how we got anything done with Marty, and Brooks [Ashmanskas]. We just laughed from the moment we got in the rehearsal room until we left. That was such a small cast and we all still really love each other. Marty was such a great leader. He was such a generous person, period. To give someone like me the 11 o’clock number in his show, it speaks to his generosity and the kind of human being he is. Also, the way he is in his life, no entourage, no ego, just a regular guy.

I learn a lot from watching people I meet who are celebrities, the way they are beautiful, kind, and generous human beings. It teaches me so much on how to navigate this business. When you come offstage and there’s a little kid in the corner who’s afraid to come and say hello, that’s the kid I want to talk to. And that’s what I learned from Marty. That kindness is everything. And to be über-talented, too, it’s crazy.

For those who don’t know, describe, not in the sendup way as it was in the Marty Short show, but really what is the “Big, Black Lady Song” and how did you get to a point when you felt, “No, I don’t want to do that role anymore?”

There’s sort of this notion with Broadway shows, a point in the show where a black person comes out and sings a big gospel number or some belty thing, and it has nothing to do with the show, it’s sort of a gratuitous “Let’s do a big production number.” I got to a point in my career where I thought, “That is really not interesting to me. I don’t want to go into shows like that. If I’m going to do a Broadway show, it has to have some kind of gravitas, or this character I play has to do something, nurture another character, or do something before she sings.”

Right around the time I was complaining to my agent about these kinds of shows, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman called me and said, “We wrote this for you, we know you have a sense of humor, let us send it to you and you tell us what you think.” It was Shaiman singing on the recording, and as soon as it got to the line, “If you want a hit, learn what Sondheim doesn’t know, and let a big black lady stop the show.” And I thought, “This is exactly what I was complaining about!” It was so funny, and the lyrics were so great. I just had the best time. It was perfect timing.

I could be reading between the lines on your resume, but you were doing a lot of guest spots on TV dramas, and it looks as if you made a choice not to do that anymore. If I’m wrong, tell me, or if I’m right, why did you stop doing those shows?

You’re very perceptive in that way, but what I made a choice to do was to stop doing day players or guest spots. I really want to do bigger roles. It’s not that I don’t want to do television. I want to do television in the way I want to do it. But those scripts and auditions can be few and far between. So my agent and I are to continuing to try. We had a great pilot season last year, a pretty good one this year. I’m just plugging away. There is this role for me, or a slew of roles out there. I believe that. I stay ready and it’s going to present itself. I don’t want to do the same thing over and over again. I want to move forward.

Tell me about Covenant House. How did you come to be involved? Did the subject matter of Newsies influence that choice at all?

No, because by the time I did Newsies, I had already been involved with Covenant House. About 10 years ago, a friend of mine, composer Neil Berg, asked if I would sing a song at a benefit concert for Covenant House and I said, “OK.” At that rehearsal and sound check, I found myself in the green room, hanging out with the kids. Lots of them, who were black and brown kids, started picking my brain. “What is it like to be on Broadway?” and “I can’t believe you’re talking to us!” and that kind of thing. I really enjoyed it, so I let Neil and the people there know, “if you let me know the date for this event next year, I would really like to be involved.” I did that for a couple of years.

Then, unbeknownst to me, the president of Covenant House, Kevin Ryan, had been observing me with the kids, and he wrote me a letter asking if I would like to be on the board of Covenant House International. I was sort of flattered, and confused, because I had never done that before. I asked for a meeting with him and asked, “What is it you think I can bring to a board?” My limited idea of a board is businessmen who write big checks and give money. I know I look like a million bucks onstage [laughs] but I asked him, “Is that what you’re looking for?” He said, “No. We’re looking for diversity on our board, and for your heart, the way you are with these kids.”

I said “OK,” because I can bring that all day long. That’s just me being myself. So here we are nine years later. I love it. I love these kids. The least interesting thing about them is that they’re homeless. They’re my heroes because they can articulate their dreams and goals to me, in spite of their circumstances. When I was doing Newsies, it was a perfect marriage. We had some kids from the shelter come to the show, and the kids in the show did a Talk-Back for them. It was a wonderful experience.

The past six years we’ve done a sleep out, where we raise money for the kids of Covenant House and the Broadway community sleeps out on the street for one night to raise money and awareness. It’s a perfect thing to bring my family, my Broadway community, into this charitable space. A lot of our stage doors are just down the street from the shelter, and a lot of our kids are walking past stage doors every day. I remember being a kid and older people saying, “You have to give back, you have to help.” I didn’t even know this was a part of my life that was a void until Covenant House filled this space for me. It really is a joyful thing to give back and spend time with these kids.

You like to read backstage. Do you have an all-time favorite book?

First of all, I love Dickens. When I was in rehearsal for, I think it was (Mis)understanding Mammy, it was a one-woman show and I had so much to learn, and the director, David Glenn Armstrong, would say to me, “We’re going to put six pages on its feet every day.” At the time I was reading Little Dorrit. Dickens is so expressive, I could see the characters in my head. They all had funny names. I remember having to put the book down so I could learn my part and doing a whole ritualistic thing at my dining room table. “I have to put you down now, but I promise I will be back.” [Laughs.] And the characters would be frozen in time. I just think reading is the greatest thing.

How did you start performing with symphonies and in more classical venues?

Right after Martin Short closed, I got a call from John Such, who is now my manager for the symphony work, and he had this program called Broadway Rocks, and it was three or four singers, and he was looking for a black girl who could sing songs from Dreamgirls, The Wiz, and Hairspray, so he was looking for that girl. I auditioned for him and the very first show I did was with the Cleveland Orchestra. It went really well, so I got more and more bookings of that particular program, and then in the midst of that I began to meet conductors who were principally pops conductors, and they would say, “What kind of program would you like to sing? Let’s build a program around you.” That happened numerous times, so I was able to parlay this concert work to another whole part of my world.

When I first started, it was just a way to get between this Broadway show closing and auditioning for something else. You still have to eat and pay your rent and living expenses, and concert work was a way to do that. And now it is the bulk of my career. It’s amazing. The last couple of years, working with conductors like Steven Reineke, Stuart Chafetz, Michael Krajewski, John Morris Russell, they are at the top of their game in the symphony world, and are kind of bringing me along. Last year was Ella Fitzgerald’s centennial, and I was flying around the world singing Ella with symphonies. It was this amazing dream that I didn’t even know I had. I love symphony work. I’m just this little black girl from Brooklyn who gets to sing on major stages with major conductors.

These concerts are Fourth of July celebrations. Is it a tough time to be patriotic, or maybe an easy time to be patriotic? How do you feel about the holiday?

That’s a very interesting question. I was just talking about this recently, because last month, for Memorial Day, I was with the Milwaukee Symphony for their patriotic pops. One of the songs was “America the Beautiful,” and the arrangement was very close to the one Ray Charles did. Very soulful, in 6/8, slow, lots of room to interpret. I personally feel that we are in a dark time in our world. It’s very difficult for me to watch the news, although I do watch it. My husband is a news junkie, so he wants to watch everything, and just before I go to bed, I have to say, “I can’t watch it. I need to shut my mind down to sleep.”

But the interesting thing about singing “America the Beautiful,” it reminds me how amazing this country really is. I have traveled all over the world and there is no greater country, in my opinion, in terms of freedom. There is so much potential in our country and at the very core of who we are as a people is goodness. And love. We take care of each other. I can get teary talking about it. With the San Francisco Symphony, on July 3rd we’re doing Gershwin, and on the 4th I am not personally singing any patriotic songs, but it will be a joy for me to be a part of that program and to celebrate Independence Day. Personally, because it is such a dark time, I consider it an active time to remember the goodness of who we are.