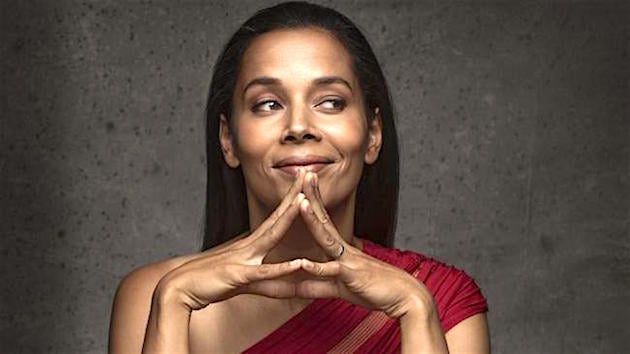

In his recent excellent biography of T Bone Burnett, a legendary record producer known for his passionate, visionary approach to a panoply of American musics, author Lloyd Sachs lauded those same qualities in singer and instrumentalist Rhiannon Giddens. “On Tomorrow Is My Turn, she reaches across a broad spectrum of styles and eras as an entertainer first and a teacher of traditions second,” Sachs wrote about Giddens’s 2015 solo debut, produced by Burnett for Nonesuch Records.

Giddens’s eclecticism, in evidence in the program she’ll perform with the San Francisco Symphony on July 20, was engendered by biracial and musically sophisticated parents in North Carolina. In 2000 she graduated from Oberlin, where she’d studied classical voice, but soon afterward turned to the banjo, fiddle, and performing and recording with Gaelwynd, a Celtic band. Giddens co-founded the Carolina Chocolate Drops with like-minded multi-instrumentalists in 2005. Evolving their repertoire from the music of the Piedmont region of the Carolinas to a heady mix of African-American styles, the Drops went on to win a 2011 Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album for their Nonesuch debut, Genuine Negro Jig, and to open for Bob Dylan. Giddens was engaged by Burnett for his contributions to the soundtracks for The Hunger Games and Inside Llewyn Davis, as well as for an all-star recording of a trove of previously unreleased Bob Dylan songs.

The peripatetic Giddens, who’s married to the Irish musician Michael Laffan and has homes with their two children in North Carolina and Limerick, has more recently appeared in the TV show Nashville, been declared Folk Singer of the Year by the BBC, won the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, and released a second, delightfully diverse solo Nonesuch album (Freedom Highway). She also continues to concertize in different settings that showcase the many appealing qualities of her clarion, sweet, elastic, and sometimes forthright singing. Giddens spoke with SFCV from a tour stop in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Tell me a bit about what encouraged you to cultivate a hybrid approach?

I started off hearing folk revival and bluegrass and commercial country, and when I grew up singing with my family, we sang that kind of stuff. I was in youth choir, and learned to sit up straight and sing with an ensemble, but I didn’t really know anything about classical music. But when I went to Oberlin, I just fell in love with the whole [classical] thing, so I associate that with joy. I stayed long enough in that world — I did a year of grad school, a bunch of operas — to really get a classical voice. When I was in classical, I was all in. I didn’t listen to anything else.

Any particular classical role models?

I really loved Anna Moffo, her early recordings, where it was just easy and beautiful and sitting right in the middle of the sound. Anna singing “Ach, ich fühl’s” (Oh, I feel it) kills me. I’ve always been drawn to the lyric voice that just sort of effortlessly soars above, and spins. I really loved Eleanor Steber, and of course, Leontyne Price, whom I look at more as the artist I am now, because of her vocal production.

Where did you go after your classical training?

I got into Celtic music, and learning how to sing with a microphone, which I’d never had to do.

How did that happen?

My name is Welsh, I’d always been kind of interested, and then I started seeing someone who was a Celtic speaker, and I just completely fell in love with the whole culture.

And you went elsewhere from there.

I got into black banjo history and the string band movement, then started studying with an elder fiddler, sitting and playing with him for hours at a time. I feel like you’re given those opportunities. I was given a voice, and as long as I follow that, everything feels right. I spend enough time in each thing to really get a thorough grounding in it, ’cause I don’t really believe in dabbling.

But you’re not tempted to devote a recording to a single genre

That’s a good question. I’m not a genre-based artist, I get bored. American music is a mixture that turns into all these genres. That’s when I’m the happiest. So a program like the one in San Francisco, I’m lovin’ it!

What about what’s listed as “Various Selections” on the Davies Hall program?

We’re doing some pieces from my new record that are being orchestrated by Gabe Witcher. He’s kind of a unique figure, the way I am, in that he can play and read and all that classical vibe, but he plays bluegrass and all the rest of what he does with the Punch Brothers [described as “American country-classical chamber music” by the New York Times]. So he can pull out those colors, as you do in orchestrating, but stay true to the vibe of the original song. It’s a sound that’s somewhere in-between.

Between classical and folk?

Yeah, walking that line. It’s kind of a new era for classical organizations. Not all cross-genre things work, but if you hit upon the right combo and the right people to do it, it can work really beautifully.

And the other selections at Davies?

“Waterboy” may be the closest to classical technique. Of course, it’s based on the Odetta version, and she was a classically trained singer. [Odetta Holmes, a popular folksinger in the 1950s and ’60s, studied opera as a youth.] For me to sing like that, like I was first trained to sing, using all my breath and posture, is a different head space.

Literally.

Yes, lifting that palate and reengaging the breath in a deeper way.

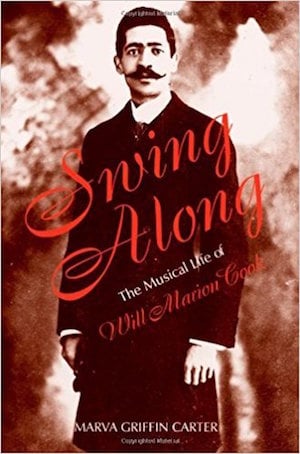

You’ve included Broadway selections by Will Marion Cook on your SF Symphony program, I’m assuming you think we should be hearing more of his music.

This is a big piece of American musical history and African-American history which is neglected. I never learned about Will Marion Cook in college, which I find very troubling, because I went to Oberlin, and he went to Oberlin to study violin, so it’s amazing that I never crossed his path. He studied briefly with Dvořák, and he wrote some very beautiful pieces.

How did you find him?

I came across a biography [Swing Along, by Marva Griffin Carver, Oxford University Press, 2008]. Then I ended up going to colleges that had put his sheet music online, downloading it and going through it. Grant Llewellyn, at the North Carolina Symphony, said “We want you to sing with us, do you have any projects,” and I said, “What about these?” And we got them orchestrated by a great guy in Seattle, Aaron Grad.

There was this whole era before Porgy and Bess, where there was a flowering of black-run, written, composed, and performed musicals on Broadway. And because they were partially in blackface, and the books were terrible, people tend to forget about it. I’m excited to air them, because I don’t think they’ve been done with orchestras since they were originally done, in 1906 or whatever. I’d love to get Cook’s songs republished, because I think they’re great for beginning voice majors, especially black ones, who are thinking, what else have we written here?

And there’s more for all of us to discover, or rediscover.

There was this whole discussion going on with black intelligentsia in New York at that time, that our vernacular music is worthy of being on stage. We should be proud of where we’re coming from, rather than just trying to write Western classical music, and that’s where Will Marion Cook came from. It’s not like these are substandard compositions and we need to hold them up just because black people did them They showcase a time period and a vernacular which was in an interesting spot, classically inflected. And I was attracted to them first because they’re great songs.

I’d imagine that the program at Davies will also have us discovering more than one of your voices. You’ll also be doing Gershwin’s “Summertime,” and “Lonely House,” from Weill and Hughes’s Street Scene.

I’m learning how to juggle, because I’ve only been doing symphony shows for a couple of years. And I’ve got a really great voice teacher now, I’m back heavy into lessons, and I think you should probably never stop taking lessons.

Will you name that teacher?

Yeah, Neil Semer, in New York. He turned my life around. Singing with microphones, I’d kind of fallen into these habits, and he just reengaged my breath and got me back into fighting trim form. It makes me excited going into this gig, rather than scared. [Laughs]

Some of us have gotten to know you as an actress, as Hallie on the CMT TV series Nashville. Does standing in front of an orchestra without an instrument give you more of a chance to act?

I love the fact that I’m not in charge any more, someone else is calling the tempos, and all I gotta do is sing. But acting is interesting; I was supposed to replace Audra McDonald in the revamping of Shuffle Along, and they were pushing me into this Broadway style of acting, while I was trying to take what I’d learned in opera. Then I went to do Nashville right after that, a completely different style of acting — very, very subtle. The TV acting I’ve taken most to heart is how on stage now I really open myself up to being in the moment, and not thinking about how it’s looking, but really kind of letting that emotion be right there, and not be afraid of it. Combining that with the stagecraft I learned in opera and for the Broadway show feels like a really nice mix to me.

Just as you’re mixing your musical genres. Is it a good time to be doing that?

I think so. The whole thing about genres really took off with [Columbia Records and Victor Records talent scout] Ralph Peer, in the ’20s and ’30s, the idea of selling records directly to consumers, with genres and subgenres. But when you narrow it down, it starts to lose its heart. Back in the heyday of radio, you would hear all sorts of things next to each other. People always loved that, and getting back to that is gonna be invigorating for the music industry, whether it’s the classical or the pop side.

And your pop side, if it can be called that, will have you returning to San Francisco in the fall, a few blocks away, at SFJAZZ, with a band instead of an orchestra.

One of the things I like to tell classical vocal students is, there’s not just one path to finding what you’re supposed to do. People are starting to open up in the classical world that going to school for classical voice and doing auditions and getting a job as an opera singer, that’s becoming a smaller and smaller school of people who can live a life doing that. It’s really about finding what you yourself can bring that no one else can. That’s one of the reasons I got out of classical music the first time. I’m a soprano, and there are two kajillion sopranos out there who can sing as good as I can or better. What do I bring to this art form that nobody else brings? At first, I couldn’t think of it! Now that I’ve gone through all the things I’ve gone through, I know what I bring to singing an aria and with the orchestra. But it took me a path to find it. Sometimes that takes a bit of a time and a bit of living. I don’t know if that fits in your article.

It does, and it seems you’ve also been able to assure singers that if you assay — we won’t say “dabble” — in blues or jazz or pop, it’ll be okay with your voice.

Yeah, just be smart about it. And there are some vocal techniques that I don’t use. Because it’s not worth losing what I’d lose. I’m very careful about how my voice feels, I have an in-ear monitor now, I’ve experimented with microphones till I found one that’s responsive. You just have to figure all those things out, but you have to do it, it’s not academic. You have to put on a show.

As you will for us.

I’m so excited about this show! I think we’re gonna be crafting something new with the night that’s gonna be really cool!