Francesca Zambello’s production of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen is back at the War Memorial Opera house for a three-cycle run, the first of which concluded on Sunday, June 17. When it was first produced here, in 2011, it was variously described as an American Ring, a California Ring, a feminist Ring, and an environmental Ring.

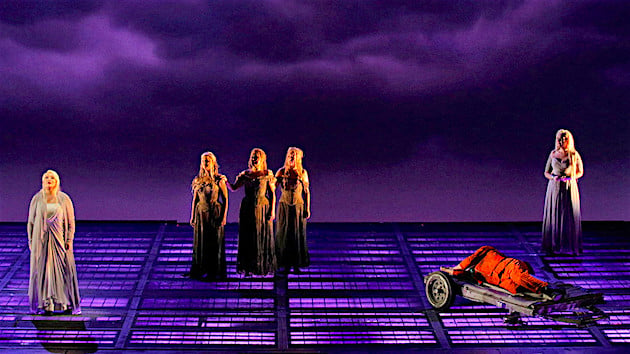

In its second staging, the environmental side of the production, which depicts a world gradually despoiled by the actions of men and the gods, came to the fore. In the current #MeToo era, the abusive behavior of Wotan, Alberich, Hunding, and other characters set a disquieting tone just under the surface, counterweighted by the power of Fricka, Erda, the Norns, and, of course, Brünnhilde.

This year brings a host of new singers in critical roles, some reworking of the staging, and updated technology. Adding to the usual stresses of staging a long and complex production, the Swedish dramatic soprano Iréne Theorin joined the cast on short notice when Evelyn Herlitzius, the long-planned Brünnhilde, withdrew just a month before opening day, because of a health problem.

Lucky ticketholders: nearly all of the changes in cast and production are neutral or for the better, making for a glorious first week under the baton of former SFO music director Donald Runnicles.

Let’s get the technical and staging questions out of the way first. With a second viewing, we have more perspective on what works and doesn’t work in the production. San Francisco Opera’s press and audience communications touted technological updates to the production, featuring new and improved projections by S. Katy Tucker and new, LED (light-emitting diode) underfloor lighting.

The projections certainly looked good, more stylish and with more of a recognizable style, though given the gap of seven years since the last production, not everyone will notice the differences. The underfloor lighting uses around a third of the electricity of the previous system, a nice greening of this environmentally focused Ring, and certainly the new system makes a good contribution to the mood of each scene. Whether it’s necessary to have projected videos over Wagner’s vivid preludes and interludes is another matter, but the technological flair is a plus at a time when multimedia productions are increasingly popular, even for symphonic concerts.

The most obvious problem with Zambello’s staging is a holdover from 2011: Das Rheingold is marred by far too much joking around, side conversation, random touching, and clownish behavior among the gods. The constant action is visually distracting and unnecessary and robs the gods of their inherent dignity. In Die Walküre, Act 2, the early byplay among Brünnhilde, Wotan, and Fricka brought forth an embarrassing amount of audience laughter during serious discussions of infidelity, incest, and marital pain. Sometimes it really is better to let your singers stand and sing and react to what they hear.

On the other hand, Brünnhilde didn’t jump on Walküre’s boardroom table and wasn’t carried around piggyback by her one-eyed father. She didn’t poke playfully at him with her spear, either. The end of Götterdämmerung came off better than in 2011, even with the Rhinemaidens, Gutrune, the Gibichung women, a child, and a potted shrub onstage and a comparatively small funeral pyre burning.

A subtle gesture added brilliantly to the terror of the last scene of Act 1 of that opera, where the disguised Siegfried kidnaps Brünnhilde to give her to Gunther: Brünnhilde reaches under the Tarnhelm to touch Siegfried’s face, recognizes him, and is consequently horrified and confused, unable to understand what’s happening to her.

And perhaps the greatest strength of the production remains: a splendidly staged and remarkably sympathetic Siegfried that flew by. In 2011, part of its charm was the surprisingly sweet Siegfried of Jay Hunter Morris, a handsome man with a beautiful voice. With the young heroic tenor Daniel Brenna stepping into the role this year, some of the sweetness and charm is lost to a more conventionally brash portrayal of the character. Still, the opera really did come off as a scherzo, a comparatively light moment in the Ring despite the deaths of Mime and Fafner. The encounters between the Wanderer and Mime, Alberich, Erda, and Siegfried retain their tremendous emotional power and depth.

San Francisco Opera planned this Ring as carefully as possible, and while bad luck forced the company to find a new Brünnhilde late in the game, good luck brought them a wonderful singer in Iréne Theorin. The soprano’s only previous appearance here was as Turandot, a short, high role that makes rather different demands on the singer. She possesses all the power and projection needed for Brünnhilde’s big moments, but she also sings with a hundred dynamic levels between pianissimo and forte, enabling her to bring a rare delicacy and subtlety to the role. Add to this that she’s a strikingly beautiful woman and a fine actor who had obvious chemistry with Brenna, and you have a complex and human Brünnhilde.

New to San Francisco, Daniel Brenna was audibly cautious for the first two acts of Siegfried, a sensible choice for a tenor singing such a long and demanding role in a large house. He opened up in the last act for his meetings with Wotan and Brünnhilde and sang with impressive ease for the first part of Götterdämmerung. Still, there’s some worrisome constriction in his voice, and, late in Götterdämmerung, too much barking. Siegfried’s death scene would be ever so much more effective sung more lyrically.

Greer Grimsley brought a powerful bass-baritone and an incisive way with words to his portrayal of Wotan. No stranger to the role, his dramatical and musical confidence made him very much the center of the show. Falk Struckmann, making his San Francisco Opera debut, has many of the same virtues as Grimsley: a big, responsive voice and long experience made him a suitably malevolent Alberich.

Štefan Margita remains a dazzling Loge, singing with the same brilliant ease and wit as in the 2008 and 2011 productions of Das Rheingold. David Cangelosi, returning as Mime, is still an effective actor, if more worn and less steady than previously. Mezzo Jamie Barton brought power, nuance, and beauty to Fricka, Waltraute, and the Second Norn, particularly her hurt, yet commanding, Walküre Fricka. That performance seemed to single-handedly raise the heat level on stage considerably.

Like Brenna, our returning Siegmund, Brandon Jovanovich, could also sing with more lyricism. He has the weight and power, but the role seems a bit too low for his best singing, and too many phrases were hammered that could have been caressed. He was again a fine Froh. Raymond Aceto was again a suitably barbaric Hunding, handling his Sieglinde roughly, and a good Fafner. Melissa Citro’s voice has filled out and darkened, and she sang Gutrune far better than in 2011, although I’d quarrel with Zambello’s shallow conception of the character.

Andrea Silvestrelli remains a touching Fasolt, lovesick over Freia, and an overwhelmingly dominant and manipulative Hagen. Brian Mulligan sang, as always, with impressive tonal beauty and firmness of line as Donner and Gunther. Ronnita Miller is a true contralto and sang flawlessly as Erda and the First Norn, though one might wish for more hooded mystery in her Erda. Stacy Tappan’s visible Forest Bird remains a delight. Tappan, Lauren McNeese, and Renée Tatum were superb Rhinemaidens, beautifully blended, yet each has such a distinctive sound that you could easily follow their individual lines. Julie Adams sang Freia with a lovely fresh sound; can’t someone find a less frumpy costume for the goddess of youth and love? Miller, Barton, and Sarah Cambidge were an authoritative Norn trio, although I found the big cables they weave less persuasive and interesting than in 2011.

There’s just one significant disappointment among the singers, and it’s a surprising one. At the first Walküre, the great soprano Karita Mattila sang poorly as Sieglinde, with hollow tone and a good deal of sliding into pitches rather than landing accurately on them. Without hearing her later in the run, there’s no way to know whether she was simply having a bad night or is grievously miscast.

No Ring production can succeed without a fine orchestra and strong leadership, and as long-time operagoers know, Donald Runnicles and the San Francisco Opera Orchestra make a splendid team. Runnicles, a great conductor of long and complex works, led a performance of breadth, subtlety, and beauty, full of telling detail. The orchestra played tirelessly and beautifully, with a warmly blended and layered sound, over the many hours of the cycle. The brass sections were especially impressive, given the demands Wagner makes on them, playing with unforced power.

The entire orchestra joined the cast and crew on stage for the curtain calls at the end of Götterdämmerung, a classy and well-earned reward. And Runnicles personally brought coprincipal horn Kevin Rivard, who played Siegfried’s horn calls, out of the orchestra to stand with the solo singers.