Superficially, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s enigmatic 1968 vocal work Stimmung represents a succinct distillation of several of the countercultural currents sweeping through the arts and society at the time. Spontaneity is foregrounded, as the piece relies on inexact mixing of vocal parts and improvisatory choices from the performers throughout. Democratic collaboration is valued over hierarchy, as the performers must take turns as lead soloist and conductor. Intercultural religious mysticism reigns, as the singers incessantly intone “Vishnu,” “Ahura Mazda,” “Hallelujah,” etc.

But Stockhausen, already 40 at the time of composition, cut his musical teeth not in the streets of Haight-Ashbury, but in the incredibly dogmatic, mathematic, and precise classrooms of “advanced” post-World War II European art music. The grand ambition in these arenas tended more toward “total organization” than freedom of expression. The two sorts of ambition interwoven together, as in Stimmung, makes for fascinating, if sometimes exhausting, listening, as San Jose’s Voices of Silicon Valley wonderfully demonstrated during a rare performance of the work on Sunday.

Conductor Cyril Deaconoff — a composer working with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s Technology and Applied Composition program, which collaborated in the performance — designed the evening’s set around a vague theme of memorial and healing for the occasion of Armistice Day. The opening half featured inviting and warming, though uninventive, arrangements of two pop favorites, U2’s “MLK” and Fleet Foxes’ “White Winter Hymnal,” enthusiastically wrought by the Voices of Silicon Valley.

The two other openers — Deaconoff’s own premiere Our Time and Sympathy by Bruno Ruviaro and Scot Hanna-Weir — both gestured mildly in the direction of Stockhausen the electronic music pioneer. Deaconoff’s piece featured short, affable, even jingle-like numbers for the singers divided from each other by a glass-breaking electronic punctuation. The vocal pieces moved through ideas confidently, doing well not to make too much of each building block but maintaining coherence. Yet the electronics seemed an afterthought, and a hand-me-down one at that.

I imagine that by his ambiguous title, Deaconoff intended some kind of statement about the fragility of good spirits today, but this failed to come across with any force. Sympathy, based on the canonical Paul Dunbar poem of the same name (“I know what the caged bird feels ...”) shined in parts, with the singers again leading the effort successfully. It also offered the novelty of the audience being asked to call up several online bird chirping tracks from their smartphones for use during the performance, an idea which totters on the brink of gimmick. Nevertheless, the dynamics of the asynchronous chirping of 30 or 40 smartphones meshed unexpectedly well with the chamber singers and the end of Sympathy came across confidently and polished.

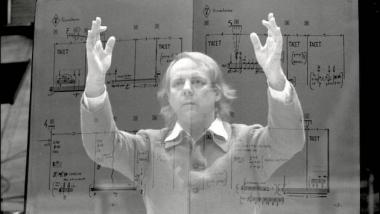

Stockhausen’s Stimmung gives the music theorist plenty to delight in. The composer structures the piece around the overtone series in a strictly organized way, invents original graphical notation to instruct the singers on their options at various points in the piece, and almost exclusively employs the singers in wobbly, humming, droning styles of singing that are distant from the Western repertoire.

Yet the experience of listening to a live performance of Stimmung depends on the listener’s willingness and ability to buy into the meditative proposition on offer. Frequently on Sunday I found little difficulty in this, especially in the more advanced stages of each of the “models” the piece is divided into, where the singers have a chance to diverge more widely from each other and larger harmonies have a chance to form. Without question, Stockhausen composes, or prompts, many passages that are unimpeachably beautiful and inimitably iconoclastic. The restarting that must take place at the head of each section, in which the performers reiterate the new idea many times, requires more focus (or abandon) to appreciate.

But there’s a perfectly intentional structural reasoning behind this: One meaning of Stimmung is “tuning,” and that pulsating movement from unison outward and back breathes through the piece. Although there are few classically difficult vocal passages in the work, performing it well takes formidable resolve, not only to maintain pitch and timbre through very long-held melodies, but to remain alert and cognizant enough of the piece’s structure to step up and lead in turn. The Voices of Silicon Valley met this challenge brilliantly by walking that tightrope that Stockhausen strung for them: maintaining enough independent initiative and license to allow the piece to happen at all, while constantly keeping the other eye on the choices of colleagues and the strict long-term structural directives.