Haydn wrote 68 string quartets; Bedřich Smetana wrote just two, the first at age 52. You get the sense that he waited until he had something he couldn’t say in any other way.

Unusually, there are only five pieces of chamber music in the prolific Bohemian composer’s output. When Smetana changed medium, it mattered. He nicknamed his String Quartet No. 1 in E Minor “From My Life,” and from his letters we know just what this music has to tell — not least about the tinnitus that within months progressed to total hearing loss and eventually madness.

We didn’t get the full story in the Viano Quartet’s performance at Herbst Theatre on Tuesday, May 7 for Chamber Music San Francisco (CMSF). The youthful passion of Smetana’s first chapter did come across: Vigorous pacing made this restless music roil. But a similar approach overpowered the melodies of the slow movement, music about a tender, tentative first love. And without sway or much swagger, the polka was less a social dance than a dance contest.

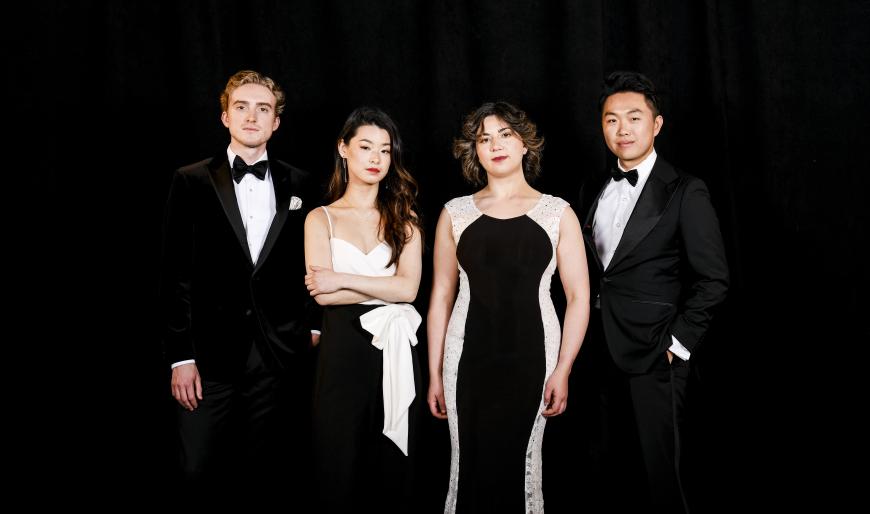

Since its founding in 2015, the Viano Quartet (violinists Lucy Wang and Hao Zhou, violist Aiden Kane, and cellist Tate Zawadiuk) has medaled at practically every chamber music competition, including Fischoff and Banff; the group is the new ensemble-in-residence in the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s Bowers Program. “The Viano Quartet is experienced beyond their years,” CMSF’s founder and director, Daniel Levenstein, said, “but with the passion of youth.” True, but I’ll look forward to hearing these players in this piece again after they’ve had a bit more time with it.

In the six years between his first and second sets of string quartets, Beethoven grappled with hearing loss and thoughts of suicide. By the summer of 1806, had he come to terms with it all? “Let your deafness no longer be a secret — even in art,” he wrote on a sketch for his String Quartet No. 8 in E Minor, Op. 59, No. 2. It’s a dark work, heralded, like the “Eroica” Symphony, by two chords — here not triumphant but tense.

These first notes were unflinching on Tuesday. In fact, the whole first movement was ferocious, its spiny melodies not lilting one bit. Played at a breathless clip, the scherzo (Allegretto) was missing its haughty elegance. Yet the same movement’s trio was remarkably fluid. Often the counterpoint here sounds pointed: “I’ll give you that theme,” Beethoven seems to say about the Russian song whose inclusion was likely mandated by Count Alexei Razumovsky, the Russian ambassador to Vienna who commissioned the quartet.

And how pretty the slow movement was. The heavens inspired Beethoven to write these vistas of simple chords. In a novel way, the two violins complemented each other in this performance, the second violin’s coloratura crossing, then rising far above, the dramatic tenor of the first.

“Viano” is a word these young artists coined to represent their coming together as one instrument. Certainly, the ensemble’s unison passages were flawless in Haydn’s Quartet in D Major, Op. 64, No. 5. Still, this is a first violinist’s piece, and Wang, steering the group with silvery sound, rose to the occasion and dazzled, especially in the marathon passagework in the hornpipe finale.

Written at the end of Haydn’s 30-year tenure as music master at the Esterházy court, this quartet later became known as “The Lark.” The bird makes a beautiful and elaborate song; here, so did the Viano Quartet.