How old is the grief-struck speaker in Schubert’s 1827 song cycle Winterreise?

In a way, by transmuting poet Wilhelm Müller’s somewhat earthbound texts into transcendent art, the composer made that question largely moot. The figure who “arrived a stranger, / a stranger I depart” is at once ageless and timeless, even as the poems describe a romantic intensity bordering on bathos that only the young feel quite so keenly.

The age issue arose on Sunday afternoon, March 17, when the tenor Mark Padmore, 63, and pianist Mitsuko Uchida, 75, performed the work in a Cal Performances presentation at Hertz Hall. In 75 minutes of soul-baring confession, the pair brought both the perspective and limitations of maturity to bear on the songs. Tempos tended to be patient and extended by rubatos. Passions were tempered with rueful reflection, especially at the keyboard, where Uchida infused Schubert’s rippling phrases and subtly pointed key changes with a sense of contemplation. She was the measured center of a performance that was not without its shortcomings.

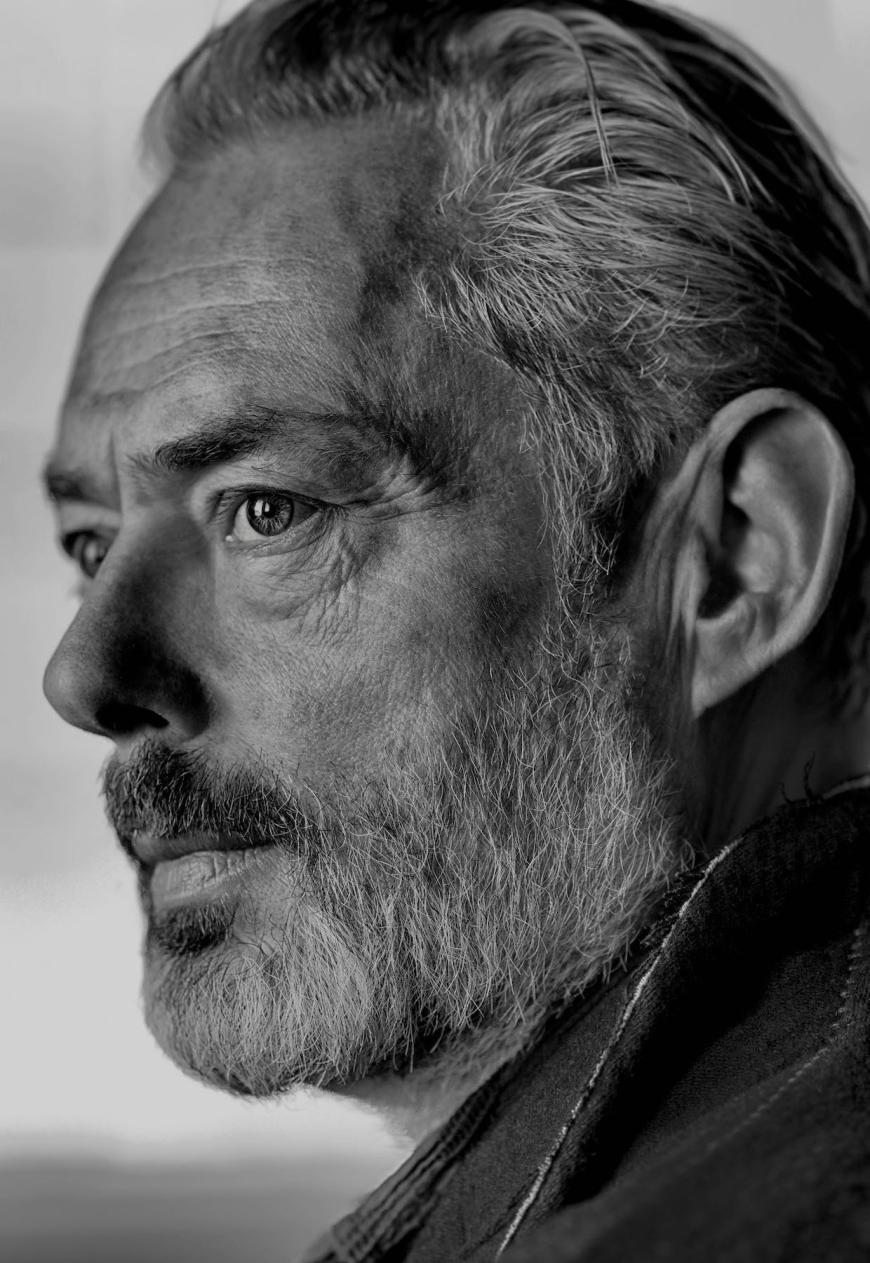

With his silver hair and beard, wide eyes and anguished, clutching gestures, Padmore registered as a man whose lost love had metastasized into something desperately existential. His voice was more raw than radiant, at times unruly, phrases occasionally ragged and high notes stretched and flattened, as if purity of sound were some polite nicety compared to convulsive feeling.

The effect was dramatic and urgent. In spinning out the opening “Good Night” (translations from the German by Richard Wigmore), Padmore bore down on the repeated lines, amped up the volume to a nonnegotiable demand — “Why should I tarry longer / and be driven out?” — and gazed up inconsolably, bidding his absent lover good night at the end of that stanza.

The tenor brought a febrile range of emotional tones to the songs. “The Weathervane” blew by with hectic abandon, only to come up short on the suddenly self-aware astonishment of the word “hearts.” Moments later, the abject, almost catatonic delivery of the song “Frozen Tears” went hot on the closing couplet: “as if you would melt / all the ice of winter.”

In “The Linden Tree,” Uchida used the aching two-note falling figure to paint a sepia mood. Padmore replied in kind, musing on the tree’s dream-inducing shade and expressions of love carved into the bark. As if that young man’s folly were lost in time, the singer summoned the expansive darkness the tree now represents. A storm broke out, in both voice and accompaniment. Even as the music offered some measure of consolation, Padmore wasn’t giving it, tightening his voice with resistance to the rustling branches’ promise of rest.

Compelling and uncompromising as he could be, Padmore blurred details at times, thundered when a little more finesse would have done, and made his erratic pitch control and phrasing a liability in “Dream of Spring” and “In the Village.”

Still and all, these two estimable performers burrowed deeply into this cycle’s well. In “The Grey Head,” Padmore both sang and enacted a shiver-inducing cosmic shrug before plumbing time itself in the infinitude of a single night: “Between sunset and the light of morning / many a head has turned grey.”

Uchida gave the meandering melodic line in “Last Hope” an eerie sense of loss, as if tonality itself had vanished. Later on, by plunging directly from the fury of “The Stormy Morning” to “The Mock Suns,” the performers made the strangeness of the latter poem’s imagery of three suns feel weirdly, naturally inevitable.

In an afternoon frequently marred by cellphone pings — Uchida plunked out an answering note during one intrusion that required a pause — stillness enveloped Hertz Hall at the end. Peering out into some unfathomable distance, Padmore froze and stayed frozen for several long beats after “The Hurdy-Gurdy Player” died away. The audience, seized in the moment, didn’t stir or make a sound until Padmore relaxed and the applause poured down.