No piece of 20th-century music is more integrated into the DNA of the Los Angeles Philharmonic than Igor Stravinsky’s pagan-ritual ballet, The Rite of Spring. It premiered in Paris on May 29, 1913, and the LA Phil’s first performance of the piece took place on Aug. 31, 1928, at the Hollywood Bowl under the baton of Eugene Goossens. The rehearsals for that performance were the first time a full orchestra recorded the Rite, though competing versions from 1929, by the composer and the original conductor, Pierre Monteux, were the first commercially released records. (The LA Phil rehearsals were published in 2004 on the Cambria label.)

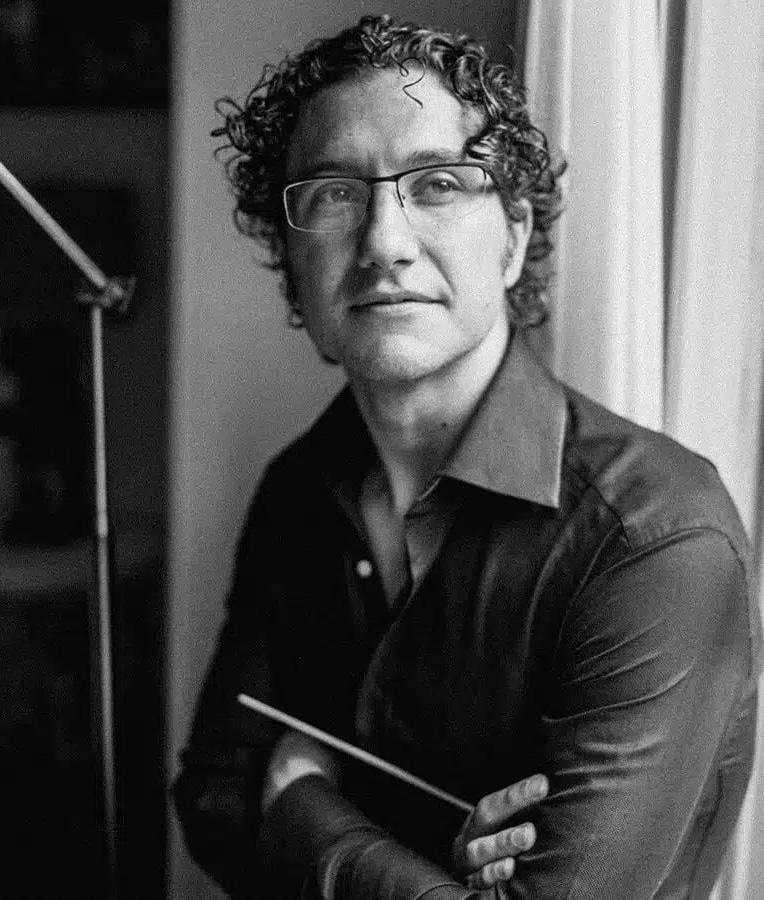

Since then, according to the LA Philharmonic’s archive, the work has been performed more than 150 times by 25 different conductors, including Zubin Mehta, Kent Nagano, Esa-Pekka Salonen (opening Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003), Gustavo Dudamel, and most recently on Thursday, Teddy Abrams.

Despite this illustrious history, Abrams’s performance may stand the test of time as one of the LA Phil’s most unusual, owing to a serendipitous mechanical interruption towards the end of the concert. Think of it as The Rite of Spring meets Apocalypse Now — a ballet for orchestra and helicopters! Abrams, an outside-the-box thinker who leads the Louisville Orchestra, might have been reminded of Captain Willard’s line, “I wanted a mission, and for my sins they gave me one.”

The all-Stravinsky concert began on a witty note with the composer’s 1944 arrangement of The Star-Spangled Banner, which was banned at the time for his unusual harmonization of the national anthem.

Ever open to unusual requests, in 1941 Stravinsky was asked by choreographer George Balanchine to create music to accompany an elephant kickline under the big top of Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus. This led to Circus Polka for a Young Elephant, which Abrams conducted with an abundance of goofy balletic charm and galumphing trunk laughs.

The mood of the evening changed decidedly with the entrance of Leila Josefowicz, the soloist for Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major. Premiered on Oct. 23, 1931, the piece was created for the violinist Samuel Duskin, with technical assistance from Paul Hindemith.

Stravinsky was fascinated by the possibility of opening the concerto with a seemingly superhuman, finger-stretching chord reaching from E to the top A. Hindemith, a skilled violist, initially judged the chord impossible to play. But it was not impossible, and the concerto soon entered the repertory.

With the assuredness of a keen-eyed marksman, Josefowicz attacked the chord (which begins each movement) with a bowstroke like a rifle-shot. Thank goodness for the Bowl’s enormous, stage-flanking video screens, because if there is a violinist more fun to watch than Josefowicz, I don’t know who it is. Her technical arsenal is vast, but so is her musicality and facial expressiveness.

It was a performance that was simultaneously classic and ultramodern: the unusual rhythmic shifts and dissonances and the slightly off-kilter lyricism were fully developed leading to the concerto’s faster-than-a-speeding-bullet finale.

Then it was time for The Rite of Spring.

It began like many other performances, with that mysterious melody from the bassoon. Skillfully wielding his baton, Abrams made the introduction develop incrementally up to that revolutionary moment when Stravinsky’s infernal machine of motor rhythms come to life. Then, as if it were a wisp of a motif, the whirr of a distant helicopter could be heard overhead — almost as if the composer had planned it.

Through the “Ritual of Abduction,” and the “Ritual of the Rival Tribes” leading up to the “Dance of the Earth,” Abrams and orchestra were totally in sync, every instrumental section linked perfectly to the others. The emotional mood rose to a massive wave-breaking climax that inundated the Bowl.

It was at that exact moment that a low-flying helicopter passed right over the Bowl, its engines thundering, its rotors chopping the air. In a perfect cross-fade from the orchestral crescendo it created a cinematic moment beyond anything you’d ever hear in the best IMAX theater. It seemed to go on and on, louder and louder, as Abrams and the orchestra waited in silence. When the metallic bird music finally faded away into the distance, all Abrams could do was look quizzically to the sky and the audience and shake his head.

If Igor Stravinsky’s ghost was looking down, he might have worn an ironic smile.