Who says opera has to be long? Over the weekend, Opera Parallèle packed two short but significant works into a 90-minute program magnificently titled Birds & Balls.

The pair of contemporary operas, by American composers David T. Little and Laura Karpman, propped each other up — with some scaffolding. Through visual and audio projections, SFJAZZ’s Miner Auditorium became the SFJAZZ Astrodome, a framing device for what conductor Nicole Paiement, Opera Parallèle’s general and artistic director, described as an “uber-story.” From his booth, the character of broadcaster Howard Cosell (Mark Hernandez, in a convincing mid-Atlantic accent) called it “the greatest sporting event ever.”

The sport of Little’s Vinkensport is the Dutch competition of finch sitting: Whose bird will sing the most calls in an hour? Poor dears. For centuries it was thought that the birds sang better when blinded; even now they’re kept in small dark boxes. But in Little’s show you feel equal pity for their trainers (a sextet of singers, accompanied by an orchestra of nine). One of them resents the sport for having robbed him of his father. Another is bored to death in her marriage. And the victors — bird and handler both — are hopped up on coke.

Royce Vavrek’s libretto deftly Americanizes the Flemish setting, and it’s an easy fit for Little’s shape-shifting score. The drunken passages slink and lurch; characters sing their frustrations in bleating, angular lines. Most often it’s fast-paced music full of intricate hocketing, which the instrumentalists, especially, handled skillfully at Saturday’s matinee.

Lingering on their storylines, it’s gratifying to get to know two of the trainers. Holy St. Francis’s Trainer — a jittery, jilted wife — is the kind of character who could veer into caricature, but soprano Jamie Chamberlin, in her Opera Parallèle debut, steered the emotional arc of the role with an almost alarming depth. And baritone Daniel Cilli, a veteran of the company, dignified the part of Atticus Finch’s Trainer, who in the opera’s poignant postscript sets his bird free.

But first, some silliness. Referencing the Thomas Hardy poem that decries birds’ maltreatment, the orchestra switches on its Baroque sound (never mind that Hardy’s not that old). A walking bass trips. And the camera pans, in larger-than-life projections (Brian Staufenbiel was the stage/creative director and scenic designer and David Murakami was the projection designer), from the veiled face of Farinelli’s Trainer (the captivating soprano Chelsea Hollow, in another company debut) to the carcass of the bird she’s mourning — balanced on a spatula.

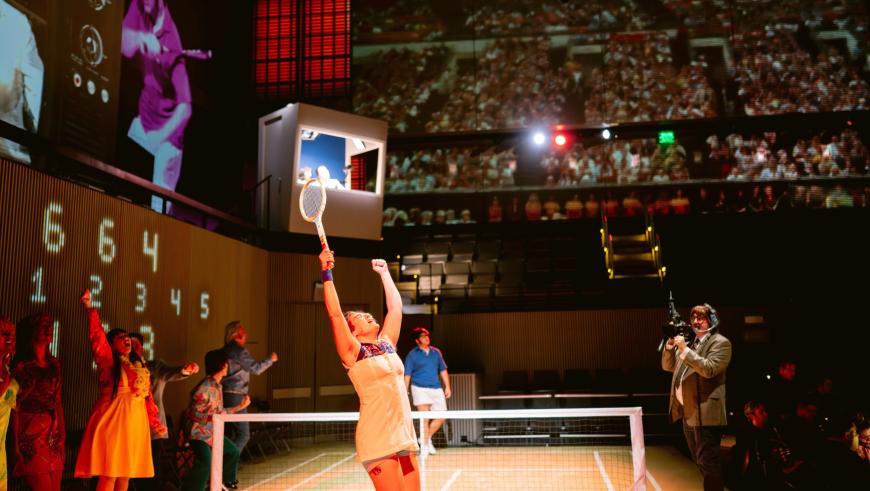

With the same sense of levity, grainy and grandly ventriloquized footage transported the audience to 1973 for Karpman’s Balls, which dramatizes the famous “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match that was broadcast to some 50 million Americans. Billie Jean King was 29 and at the top of her game; Bobby Riggs, at 55, was a seasoned chauvinist.

As Billie Jean, mezzo-soprano Nikola Printz commanded even the most expository lines of the libretto by New York Times columnist Gail Collins, and tenor Nathan Granner, playing Bobby, communicated leagues with each flourish of his racket. But this opera swings the furthest with its minor characters. The gospel-tinged ensemble was magnetic even when it was overpowered. As Marilyn, Billie Jean’s secretary (and, it’s hinted, more), Tiffany Austin crooned like the best jazz singer you’ve ever been lucky enough to stumble across at a singles bar. Best of all were the sounds of the ball, the pinging percussion (played by Joel Davel, Tim DeCillis, and Carlos José Alvarez) coalescing with the sports commentary in a mesmerizing loop.

One unforced error: the chorus of suffragettes who march into the match and dull the opera’s denouement. But “there are no perfect endings,” as soprano Shawnette Sulker (breathtaking even as a superfluous Susan B. Anthony) sang, “just brief victories to score.” Like the moment just before she wins when Billie Jean’s eyes begin to sparkle.