For an orchestra that devotes a full third of its budget to youth outreach and music education, the Oakland East Bay Symphony’s “Celebrating Youth” concert was a major event. The culmination of decades of outreach to youth in the most challenged neighborhoods of Oakland and Livermore, the concert displayed the extraordinary level of musical excellence that youth can achieve when given opportunities for musical expression.

The evening, staged in the Paramount Theatre, culminated in a thrilling performance of Tchaikovsky’s1812 Festive Overture, Op. 49, in which the Oakland Youth Orchestra partnered with the Oakland East Bay Symphony. Also on the program were the 19-year-old winner of OEBS’ Young Artist Competition, Jeremiah Campbell, who soloed in a full-blooded account of the Cello Concerto that Barber completed when he was 35. Rounding out the evening was Mendelssohn’s “Scottish” Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 56, completed when the composer was 33.

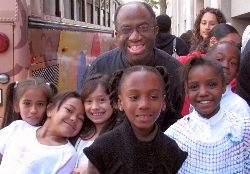

During his long introduction to the 2½-hour performance, Music Director Michael Morgan asked all symphony members who participate in the MUSE Program that teaches music to 3,000 students in Oakland and Livermore schools to stand. The number of standees was impressive. Morgan also honored a number of contributions to the symphony’s youth program. He specifically cited the addition of two more schools to the MUSE Program, and the donation of 54 instruments to the Oakland public schools. For good measure, he delivered an impassioned fund-raising appeal during a time of economic contraction, emphasizing the importance of the symphony’s outreach to youth.

Festive as All Get Out

The unquestionable highlight of the evening came after intermission, when the OYO joined the OEBS for Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, aka the Festival Overture, Op. 49 (1812). The stage was packed with players, including young students who were given solo honors on cymbals, gongs, drums, and wind instruments.

Despite the extremely dead acoustic of the Paramount Theatre, which is devoid of the reverberation essential for instrumental bloom, and which also drains color and life from music, the extra players went a long way toward delivering the sheer weight of sound that Tchaikovsky’s music requires. The performance was exciting, with only a certain lack of finish to phrases from the brass, and an occasional wrong note from same, suggestive of a less than professional level. By contrast, the cellos and violas sounded particularly round and beautiful, and a sensitive gradation of dynamics bespoke the love that Morgan and his brood invest in their music making. It was impossible not to smile during this rousing performance.

Jeremiah Campbell, former principal cellist of the San Francisco Youth Orchestra and now principal cellist of the Juilliard Orchestra, delivered a robust account of Barber’s Cello Concerto. Save for its romantic, heartfelt Andante, it’s a rather astringent work, written by a composer who presumably wanted the world to know that he could write far more than the Adagio for Strings (the orchestral arrangement of the central movement from his String Quartet in B Minor, Op. 11).

Trading formal dress for a hardly casual gray suit, blue shirt, and tie, Campbell dug into his instrument as if his life depended on it. The symphony’s strings echoed him perfectly. Campbell’s sound is beautiful and dark, and his playing masterful in the cadenza. Although intonation was suspect in the opening movement’s pizzicati, Campbell played with such authority as to merit profound applause from orchestra and audience.

To Scotland We Go

Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 56 (”Scottish”), fares best when invested with warmth and richness. Perhaps the OEBS gave it all it deserves. But in an edifice that selfishly inhibits orchestral color to ensure that its art deco architecture is rarely upstaged, the music seemed far less interesting and beautiful than it is.

Until the symphony’s finale, the lovingly played fortes never broke loose. Nor did strings soar with silken freedom. There were fine moments — the ending to the second movement was especially high spirited, and the final Allegro vivacissimo grew more exciting as it progressed — but the performance as a whole never took off.

Lift off was left to the youth. By the time it’s their turn to join the ranks of the Oakland East Bay Symphony, the organization will hopefully have a significantly better acoustic in which its music can shine.