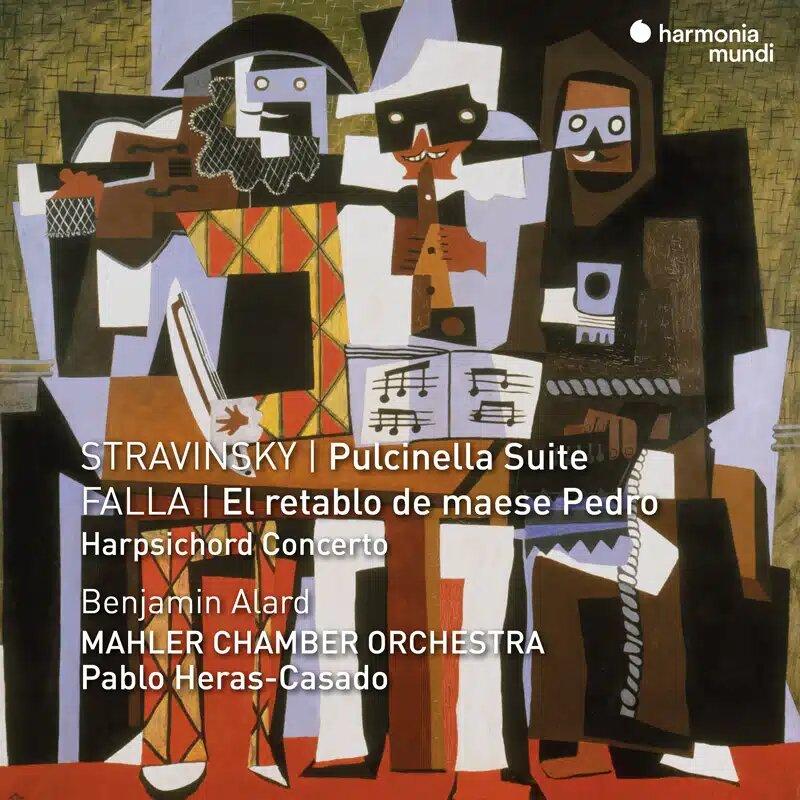

Manuel de Falla is supposed to be the embodiment of Spanish music, the composer of Andalusian-flavored works such as La vida breve, El amor brujo, Nights in the Gardens of Spain, and especially the ballet The Three-Cornered Hat. Yet there was another, lesser-renowned side of Falla — the internationalist keen on keeping up with the times. In the 1920s, he jumped on Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassical bandwagon and started looking back to older styles such as Domenico Scarlatti’s music during his Spanish residency. That facet of Falla is explored on Spanish conductor Pablo Heras-Casado’s new album with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, out now from Harmonia Mundi.

The central work here is El retablo de maese Pedro (Master Peter’s puppet show), a 26-minute one-act opera based on an episode from Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote in which the deluded old warrior drops in on a puppet show and rises in indignation to defend the honor of characters he thinks are real. Scored for a 20-piece chamber orchestra and three singers — Master Peter (the emcee), a boy who narrates the action of the puppet show, and the Don himself — the piece has the poise and objective stance of the neoclassical movement, shorn of overt Andalusian color.

Indeed, Falla’s score instructs that “the singers should make a point of avoiding every kind of theatrical mannerism in their vocal style,” with Master Peter and the boy avoiding “all lyrical feeling” and Don Quixote “partak[ing] equally of the sublime and the ridiculous.” These directives the performers meet on this recording. The part of the boy is extensive, often unaccompanied, which may be one reason why the piece isn’t done very often, and boy soprano Héctor López de Ayala Uribe sings his exposed lines stoically. Long stretches of the score are for the chamber orchestra only, accompanying the pantomime of the puppet show. The presence of a harpsichord throughout underlines the neoclassical idiom indelibly, and Heras-Casado has a good feeling for the idiom.

Falla’s next venture into neoclassicism was a Harpsichord Concerto of Baroque-era brevity (about 13 minutes). The piece was a novelty at the time, when the harpsichord was just beginning to awaken from its centuries-long slumber through the advocacy of Wanda Landowska (for whom it was written). A witty first movement gives way to a stately, somewhat severe slow movement and finally a sprightly finale that practically screams Stravinsky, anticipating passages of that composer’s Violin Concerto some five years in the future. Benjamin Alard is the harpsichordist here, and he teams up with Heras-Casado in a highly pointed rendition without racing the tempos much.

To complete the neoclassical lineup, Stravinsky shows up with the suite from Pulcinella, the ballet that got the bandwagon rolling. Aside from some Baroque trills in the strings (starting on the top note), the performance adopts a lean modernist approach, with Heras-Casado setting a mostly speedy pace while the engineering maintains pinpoint clarity in texture. The Mahler Chamber Orchestra is due at this year’s Ojai Music Festival (June 6–9), and its excellent playing here makes the gig something to look forward to.