The San Francisco Symphony’s program last week, Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony and Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas’s own piece commemorating the diary of Anne Frank — two works embodying the struggle of the human spirit against adversity — was planned long ago. Suddenly, Tilson Thomas’s From the Diary of Anne Frank, which he wrote nearly 30 years ago “from the perspective of looking back at events that seemed to have come to an end,” as he puts it, has become relevant again after the anti-Semitic attack on the Pittsburgh synagogue three weeks earlier.

That also puts this concert in a sequence of recent events offering music as a symbol for liberty and a healing process for the stressed human spirit, a theme I encountered at Kronos Quartet’s “Music for Change: The Banned Countries” concert at Stanford a month ago, and which has animated several events SFCV has reviewed since. It seems suddenly to be all over, sometimes by deliberate acknowledgment and sometimes by happenstance. But in truth there is no happenstance. Music’s celebration of human rights, its depiction of human aspirations, and its contributions to human healing are constants.

From the Diary of Anne Frank, as I heard it conducted by its composer on Saturday at Davies Symphony Hall, is a major work evoking strong emotions. It’s built on a lengthy selection — about 1,500 words — from the diary that Frank kept in Amsterdam during World War II, focusing more on her faith in the human spirit than on the specifics of her life as a Jew in hiding. Tilson Thomas made the selection in collaboration with the original narrator, for whom the work was written, the late Audrey Hepburn. This week’s narrator was operatic mezzo Isabel Leonard. She spoke well, with only a few odd emphases.

Leonard’s voice was amplified, necessary for a speaking part in a work where the music rarely goes on hold to allow space for the narration. It stops entirely once, for a lengthy self-evaluation by Frank, whose wry observations also give the audience its only opportunity to laugh. For the most part, the music goes on underlining the diary’s thoughts whether the narrator is speaking or pausing. The moods vary, from the darkness of the suffering of war and the terror of hiding from the Nazis, to an almost scherzo-like lightness for a section depicting Frank’s love of nature. That the music was as interesting as the spoken words was the most distinctive feature of the work.

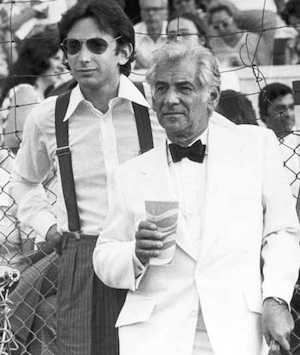

The compositional style inevitably brought up thoughts of the works of Tilson Thomas’s mentors, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein. The quieter passages bore a particular resemblance to Copland’s contemplative wistful style in works like Our Town, occasionally rising through firm exhortations to the noble. One Copland work I was not reminded of at all, however, was the Lincoln Portrait, although that is also narrated. Tilson Thomas’s style entirely lacked the formal grandiosity, or the subsidiary role, that Copland employed for Lincoln.

Some of the more energized passages resembled Bernstein, often with the heartier flavor of Copland mixed in. There are bright and flashy parts with crisp, percussive punctuation. The agonized section where the Frank family goes into hiding gave off a definite whiff of the Jets and the Sharks from West Side Story. Some solo passages, particularly one for bass trombone, bore the shape of Shostakovich solos, though the accompaniments never carried that composer’s flavor.

It should in no way be thought, however, that this music is pastiche. The emotion always felt like the composer’s own, never something borrowed or pasted in. And there was some notable material of an original kind. Accompanying part of the description of the family in hiding was a brittle ostinato figure that began as a solo for the last violin, taken up by other individual instruments in a chaotic canon.

Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony was advertised for this program as an “epic testament to liberty,” a description that could apply to a number of Beethoven symphonies. Tilson Thomas made sure that this evening it applied to the Eroica. This symphony is a massive and heavy work that, unlike the Seventh, cannot be made light or airy. What the orchestra could and did do was make it uplifting. The heavy chords in the first movement had the same pointed and energetic crispness as heard in the Diary. The funeral march was majestic and hopeful, rather than tragic or droopy. The Poco Andante interlude in the finale was likewise majestic, a last solemn look back at what the music had been through. The finale in general, after a mischievous extra pause before launching into the pizzicato main theme, was so positive and cheerful it became a veritable ode to joy, matching the one in the Ninth, the work that will be on at S.F. Symphony this week.

Tilson Thomas set the tone, but he let the orchestra do all the work. For large parts of this symphony he barely conducted at all, letting the musicians play while he merely coached them along with a few gestures, sometimes waggling his left fingers to encourage a little extra crispness in the sound. One contribution he must have been responsible for came in a contrapuntal passage for strings in the finale, which was played solo by the section principals instead of by the full groups as Beethoven had written. This clever bit of rewriting added an extra touch of sizzle to the movement.