In an April 8 Santa Rosa Symphony concert filled to the brim with instruments — electric violin, vibraphone, marimba, xylophone, glockenspiel, keyboard samplers, harps, piano, and myriad drums, gongs, and bells, to say nothing of winds, brass, and strings — the instrument that came out on top was the human voice, both in person and impersonated.

The in-person voices appeared in Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky cantata; the impersonated ones in the “Prelude and Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. The utterly nonvocal electric violin took center stage in John Adams’s The Dharma at Big Sur.

Let us begin at the end, a thrilling, blood-quickening and triumphant rendition of the 13th-century Russian prince Alexander Nevsky entering into Pskov after defeating a thundering horde of German knights on a frozen lake. The massive Sonoma State Chorus, supplemented by other local choirs, sang (in Russian), “Russia marched out to mighty battle, Russia overcame the enemy ... Whoever invades, will be killed.” Their diction was precise, their words fully intelligible, their delivery superb. They soared above the mighty orchestral forces assembled below and stole the show.

And what a show it was. Alexander Nevsky, composed in 1938, is one of the great film scores, and its narrative drive is fully evident even without its visual counterpart. Conductor Bruno Ferrandis, returning after the lengthy search for his replacement (Francesco Lecce-Chong), turned up the momentum and moved the score briskly forward. The opening section, “Russia beneath the yoke of the Moguls,” was suitably eerie and oppressive, with a four-octave, two-note chord setting the mood.

The choir’s entry in the subsequent “Song of Alexander Nevsky” was strong and precise. The basses rang out, and the sound filled the hall. The song’s final refrain — “Whoever invades Russia, shall be killed” — drove home the cantata and film’s obvious purpose of rousing the Russian citizenry against the Nazis. As the story moved forward, the chorus kept returning to that invocation, singing “Arise, people of Russia,” “Let the enemy perish,” and other phrases of that ilk, always with power and conviction.

Meanwhile, the orchestra kept up a furious pace, with standout performances by the brass and memorable sounds from the strings. The famous “Battle on the Ice” was played at a fever pitch, with the string, brass, winds, and percussion sections trading phrases with machine-gun rapidity. Ferrandis was as invigorating as ever, jumping around on the podium and swooping his arms like a raptor in flight.

The only disappointment was the solo by mezzo-soprano Jacalyn Kreitzer, who buried herself in the orchestra instead of striding forward on the stage. The solo has a very low range and it didn’t ring out, although her tone was often lovely.

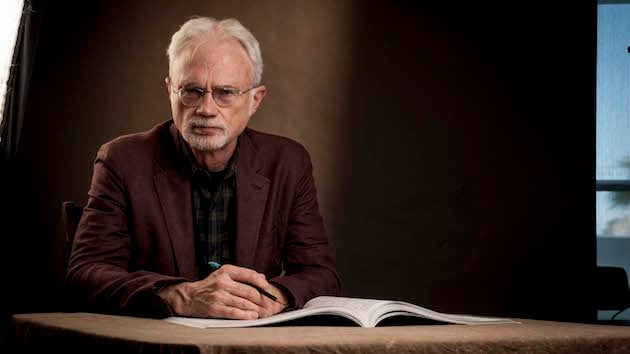

The musician who did ring out, with the help of plentiful amplification, was the electric-violin soloist, Tracy Silverman, who appeared earlier in The Dharma at Big Sur. His instrument sported two additional strings below the low G (lower C and lowest F), a bevy of pickups near the tail, and no acoustic properties. All the sound came out of two speakers on the ground behind him.

Amplified instruments conquered pop music long ago, but in the acoustic context of the concert hall, it’s hard to understand their appeal. The sound is unrelentingly harsh and devoid of subtlety, and the upper registers grate on the ears. Thankfully, Silverman did not play his violin at top volume, but he had the potential to drown everybody out.

In contrast to the overbearing violin sound, John Adams’s music was delightful, with shimmering orchestral textures and complex syncopations that sustained interest. For all the intricacy of the orchestral line, however, it mainly functioned as a drone for Silverman’s peregrinations. He displayed excellent technique and strong bowing, but he was often out of tune in the upper reaches of his instrument.

Silverman, who wowed the audience, was more convincing in his encore, a piece by rock legend Carlos Santana. Here Silverman displayed more flexibility and rhythmic intensity, but he diminished the performance by recording what he was playing and then using the recording as background for further improvisations. It was technically impressive, but it felt like a parlor trick.

The concert opener, on the other hand, was a convincing display of lush acoustics supplemented only by the instruments’ own resonant overtones. Tristan and Isolde is about as romantic and tragic as music gets, and Ferrandis evoked both qualities to the hilt. The beginning in the low strings was wonderfully hushed, and the echoing winds were a perfect rejoinder. What was most impressive, however, was the ever-so-gradual crescendo from the haunting opening to the first climactic moment, followed by a long decrescendo and another rise and fall as Tristan dies in Isolde’s arms. You could almost hear them singing.