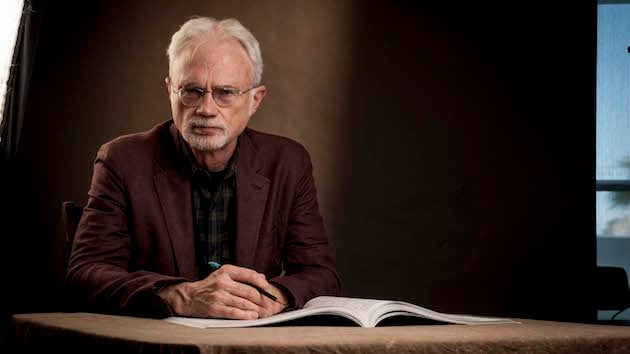

When John Adams walked onstage at the Walt Disney Concert Hall Tuesday to introduce the evening’s Green Umbrella Concert, he couldn’t help waxing nostalgic.

He pointed out the (relative) youth factor among the composers on the concert — the oldest participant, Marc Sabat, having been born in 1965, the youngest, Gabriella Smith, in 1991. They have all grown up in the cross-genre pollination, experimentalism, and eclecticism of the 1960s and after. Instead of looking to be part of a mainstream style, as in the early ’60s, composers today take it for granted that those hierarchies are gone. Adams enthusiastically endorsed that change.

In 2015 Bay Area composer Gabriella Smith received a commission from the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (established by Albert C. Barnes who invented and made a fortune selling Argyrol nose drops). After Barnes’s death in 1952, his art collection was ultimately moved to Philadelphia where it was reinstalled as it had been in his mansion, featuring Barnes’s salon style collision of multistyled paintings, kitchen crockery, and furniture.

It was here that Smith encountered the paintings and the odd manner of their display. The result was Carrot Revolution for string quartet, its title drawn from a quote attributed (questionably) to Cézanne, who conjectured that “a properly observed carrot” could start a revolution.

Smith’s creation is not likely to inspire a revolution. But within its 12-minute frame the work moves playfully in a variety of intriguing and contrasting directions, as if one musical picture were dripping into another. Like Barnes’s collection, Smith’s musical vocabulary fluctuates: There are times when the rhythm and melody is as folksy as an Appalachian clog dance. Then dissonances creep in, for a more European modernist feel. It’s also impossible not to notice the influence of John Adams (who has supported Smith’s progress for years). Skillfully and energetically performed by Nathan Cole and Akiko Tarumoto (violins), Teng Li (viola), and Jonathan Karoly (cello), Carrot Revolution was a romp through a very different set of pictures at an exhibition.

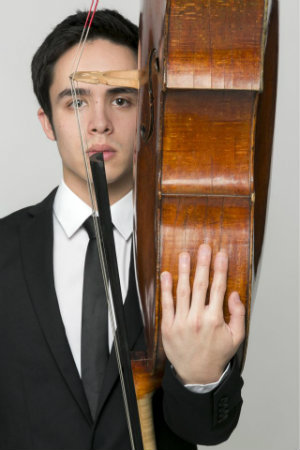

Because of his many local appearances as cellist for the JACK Quartet, Los Angeles, and Ojai Festival audiences are familiar with the artistry of Jay Campbell. Two of his performances on Tuesday — the world premiere of Sabat’s Partite Requiem (commissioned by the LA Phil) and Tristan Perich’s one-bit fusion, Formations (from 2011) — cast Campbell in a solo role.

The two pieces form a fascinating duality. Sabat’s work is as solitary as a meditation in a monk’s cell, where the soloist delves into a shadowy exploration of the vicissitudes of existence. The work’s succession of elongated single tones, overtones, and hovering harmonics were skillfully executed by Campbell who sat isolated by a single shaft of light, reminiscent of the equally “monastic” portrait of Pablo Casals by Yousuf Karsh. Throughout the piece, a few wispy Bach quotations hover as distant references.

While Sabat’s work delves inward, Perich’s Formations turns the same monk’s cell into a shimmering realm where the cello spins melodic lines around the electronic fluctuations and varying oscillations of six channels of “1-bit electronics” (binary systems extracted from the innards of prehistoric Nintendo game boxes). The effect is as if the cell were filled with seraphim, beautiful and mesmerizing, as the fluttering amplification spins a minimalist web accented by the cello. Terry Riley (minus the cello) created exactly the same effect in 1969 using multiple tape loops in Rainbow in Curved Air

Campbell also performed Eric Wubbels’s gretchen am spinnrade (Gretchen at the spinning wheel), with the composer taking the percussive prepared piano part. It’s a work that Campbell described before the concert as so physically demanding it’s like being “kicked in the face.”

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the piece is assaultive from the moment it opens with a series of repeated staccato attacks. From then on, the two soloists are like a pair of pit bulls ripping lines from the cello that are bandied back and forth with the piano whose metallic tone is accentuated by the attachments to its strings. Comfortable it is not. But it seems totally appropriate for the times we are living in.

The only orchestral piece on the program was the premiere of Sky Macklay’s Swarm Collecting. A commission from the LA Phil, Macklay said her only stipulation was that she could have up to 20 instruments of her choice. So, like a modern-day Noah she brought them onto her ark two-by-two: paired violins, violas, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, bass trombones, tubas, timpani, and percussion, with Adams conducting.

Macklay describes the ebbing, flowing, and swarming of her instrumental forces as intertwining and coming apart in a series of “messy swarms,” evocative of the “waggle dance” bees do to communicate.

The range of tones produced by the instrumental pairings grumble in blurts and blats from the tubas and bass trombones, then move in a jittery manner into the higher register wind instruments, and the pure tones of the mallet instruments. Skillful in its construction, the work communicates mostly as a well-crafted series of contrasting tonal structures, but without a great deal of emotional content to elevate it to another level.