It is no doubt unusual to begin a review with a thank you. But take it from someone whose family found itself priced out the Bay Area and impelled to relocate to the troubled paradise of Port Townsend, Wash.: San Francisco Opera is a gem. Relatively few opera houses worldwide have the budget to host the area debuts of three major stars and support them with world-class conducting and a gorgeous new “made in San Francisco” production. What a blessing.

Yes, I loved the new La traviata. With critical reservations, of course. But as the tragic plight of courtesan Violetta Valéry unfolded, our hearts aching when her death approached, I and most in the audience knew we were witnessing operatic performance at its most profound.

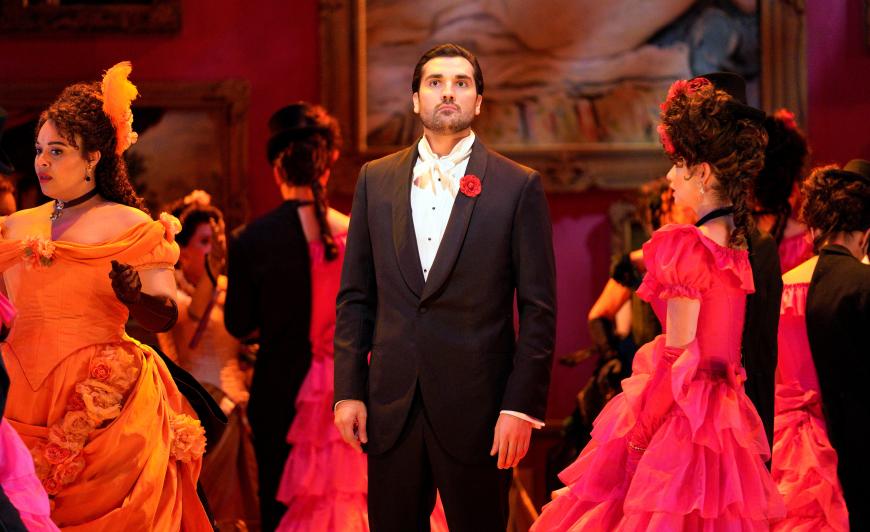

On opening night last Friday, Music Director Eun Sun Kim led the SF Opera Orchestra’s plangent, translucent, sighing, and maximally expressive divided strings in a perfectly paced Prelude, and the curtain rose on Robert Innes Hopkins new production design for director Shawna Lucey, brilliantly lit by Michael Clark. The women’s primary-colored costumes shone as brightly as soprano Pretty Yende’s irresistible smile in the role of Violetta. Not many singers can maintain radiance and shine from within while singing increasingly high-lying music, but Yende glowed through the challenge. From about two minutes in, once she had found her tonal center, she sang with increasingly alluring sweetness.

Yende’s tempos were surprisingly regular in Act 1, with little bending or indulgence in notes and passages that have customarily been stretched by earlier singers. As lovely as it was, the coloratura of “Sempre libera” was a mite cautious and metronomic, with two or three notes brushed aside and the much-anticipated high E-flat at aria’s end but briefly acknowledged. Nonetheless, Yende’s consistent beauty of voice and presence made up for the loss of what other Violettas have given us.

Power, ardor, conviction, and glorious sheen were the mainstays of towering tenor Jonathan Tetelman’s flawless vocalism. In the first act, the excessive length of his authentically 19th-century Parisian jacket may not have flattered his slim, long-legged appearance, but the voice rang free. The indulgences of so many of the great tenors who have graced SF Opera’s stage as Alfredo Germont, including Tito Schipa (at the 1924 company premiere) and Beniamino Gigli (1930), were largely absent. In the ebullient “De’ miei bollenti spiriti,” both the expressive recitative and aria zipped by faster than an Amazon Prime delivery person. But Tetelman’s passionate deployment of an instrument whose burnished beauty glows in its youthful prime gratified nonetheless. When he opened wide on climactic high notes, the effect was thrilling. Even more surprising were the few passages when he modulated his voice to sing with far more sweetness and warmth than Franco Corelli could ever muster. In duets, a few of his piano endings were so soft as to provide a velvet cushion for Yende’s higher instrument.

As the opera moved beyond the true love of Act 1, Kim’s approach to pacing became clear: keep things moving at a virtually nonstop clip at first, as though Alfredo and Violetta’s joy cannot be contained; then, as darkness intervenes in Act 2, allow the singers to slow down and express themselves. As the twin shadows of illness — the tuberculosis that took the real Violetta’s life at age 23 — and parental intervention cast a pall on the proceedings, indulge more. The male linchpins in this transition to freer tempos were the arrival of Alfredo’s father Giorgio (debuting Veronese baritone Simone Piazzola) and the increasing alpha-male aggression of Violetta’s patron, Baron Douphol (bass-baritone Philip Skinner).

Where some elder Germonts have softened the blow of their judgment and cruelty with mellifluous vocalism and flexible tempos that reflect Verdi’s roots in bel canto — think the tonal splendor of some of SF Opera’s many Germonts (including Giuseppe De Luca, Lawrence Tibbett, Mack Harrell, Robert Merrill, and Dmitri Hvorostovsky) — Piazzola sounded bottled up, contained, rather dry, and devoid of requisite swell on high notes. Given that this seems to be one of the singer’s mainstay roles, perhaps he was not in his best voice on opening night. Regardless, the lack of bloom was anything but mitigated by his stolid appearance and single-gesture acting. As contemptible as the elder Germont may seem when he nips young love in full bloom, his actions are tempered by his eventual willingness to accept the doomed Violetta as a member of his treasured family — the family that the real-life Violetta never enjoyed. But the vocal warmth necessary to underscore these redeeming aspects of his otherwise odious paternalism were nowhere to be heard. The consoling beauty of “Di Provenza il mar, il suol” was scanty at best. Listen to Lawrence Tibbett’s live 1935 performance from the Met and weep.

Skinner remains a towering knockout of a performer and actor, his every move arresting. Adam Lau (Dr. Grenvil) sang superbly, and the beauty of Taylor Raven’s voice (Flora Bervoix) enlightened her appearances. Adler Fellow Edward Graves (Gastone) was another standout. I was less taken by Elisa Sunshine (Annina), who could have let her light and caring shine more in the role of Violetta’s devoted servant.

A few minuses. Isn’t it time that we moved beyond pandering to the Bay Area’s large LGBTQ community and its vital allies by gaying up the androgynous dancers in Flora’s salon with the centuries-old trope of traditionally female dress on one side and male on the other, albeit made more ambiguous by split facial appearances? As for the tutu and the whipping-the-dog number — really? Were those meant to depict decadence? Regardless, redemption in this marvelously red-cast scene came when Lucey directed all the women to slowly gravitate around the suffering Violetta in order to insulate her from the violence of men. It was as telling as it was touching.

Turning the focus to the strength of women paved the way for the ever-increasing pathos of Yende’s portrayal. At first, it did not seem possible that she could bring significantly extra weight and depth to her inherently light instrument. But as Violetta descended deeper into illness and suffering, so did voice and artistry. Phrases were elongated and notes savored. There were a few “almost got its” at the very end of arias, but so much of Yende’s singing and acting was exalted that those moments seemed beside the point. Her reading of Giorgio Germont’s letter was original, and so much else was inspired.

Yende deserved every iota of the adoration that the opening-night audience heaped upon her at opera’s end. It’s a portrayal that every music lover must see. The production runs through Dec. 3.