The Symphony set the stage for Gluzman by performing the Requiem in the first half, a reversal of standard symphonic programming, which usually relegates soloists to the opening set. The only downside to beginning with the Mozart was a long and awkward pause between the Kyrie and the Dies Irae during which latecomers scurried to their seats. Because of the break, some forward momentum was lost, though the assembled forces soon recovered.

The most notable among those forces was the chorus, more than 100 singers massed in risers at the back of the stage. They asserted their presence in the opening Introitus, enunciating “Et lux perpetua” so clearly that they seemed to be spitting out the words. In vocal quantity and quality, they were more than a match for the four soloists, who sat stolidly in the demilitarized zone between orchestra and chorus.

The soloists’ placement behind the orchestra rather than at the front of the stage seemed to hamper their performance. Baritone Jeffrey Fields was hard to hear, and tenor Corey Head was excessively nasal. In contrast, mezzo Anna Jablonski had a solid, full-bodied tone, sometimes dwarfing that of soprano Helene Zindarsian.

That energy proved infectious. By the final Lux aeterna, the auditorium was supercharged, filled with the majestic noise of Mozart in his full glory. In Neale’s hands, the composer’s final work seemed as much a celebration of life as a meditation on death.

The audience of some two thousand rose from their seats to deliver a standing ovation and then kept standing as they began the long process of filing out of Memorial Auditorium’s interminable rows for intermission. The last commission by Frank Lloyd Wright, the auditorium has good sound but poor crowd control. Wright didn’t believe in center aisles, so if your seat is in the middle, you’re lucky to get out for a quick breather before the lights dim for the second half.

Fully Integrated

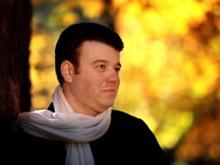

When the second half did begin, soloist Gluzman strode on stage in a long black coat, holding his Stradivarius aloft. He planted himself to Neale’s left and began swaying back and forth during the stately orchestral introduction of the Brahms concerto. By so doing, he established himself as an adjunct member of the orchestra, enacting its musical flourishes through body movement.When Gluzman began to play, the sound that emerged from his Strad was both liquid and golden. He has razor-sharp intonation, and his bowing is superlative. His first passage complete, he flung the violin off his shoulder and pirouetted to commune with the orchestra. His moves throughout the movement were emphatic, accentuating both his commanding fortissimo double stops and his evanescent high notes in the upper reaches of the violin.

No matter what the volume, pitch, or speed, the most distinctive characteristic of Gluzman’s playing is his phrasing. Every line has a clear beginning, middle, and end, and the transition from one phrase to the next is often breathtaking. This ability shone forth especially in the Adagio second movement, where each phrase seemed to float out like a feather suspended in air.

By the triumphal finale, Gluzman was clearly enjoying himself. He made the devilish runs up and down the fingerboard seem as effortless as careening down a slide, and he leaned back when landing on the highest notes. At times, he even seemed to mouth the melody, as if his violin weren’t enough. Again, however, the phrasing and transitions carried the day.

The Dance of the Blessed Spirits made a fitting encore, in more ways than one. It not only showcased Gluzman’s considerable talents, but also brought Mozart back into the equation. After an earthly Requiem, it’s heartening to contemplate eternal blessedness, spiritual or otherwise.