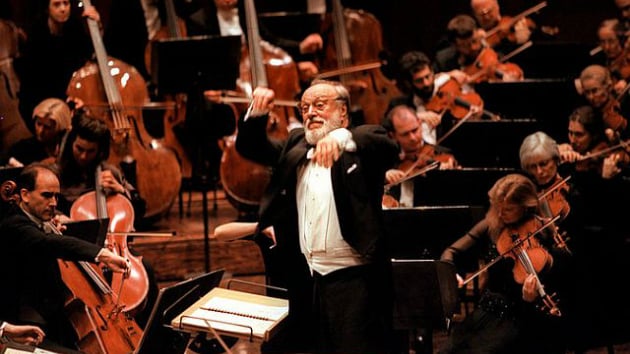

Kurt Masur, who died on Saturday at age 88 of complications from Parkinson's disease, was among the most prominent conductors of the 20th century and also remembered for his historical role in politics.

Highly regarded by the communist East German government when he led the Dresden Philharmonic and then the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra for three decades, Masur used his position and relationship with party bosses to help prevent a deadly crackdown on the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations. That mass movement led to the opening of the Berlin Wall and the end of hard-line communist rule in East Germany, followed shortly by the collapse of the Soviet Union and its empire in East Europe.

Masur was urged to run for the presidency of the reunited Germany, but he only wanted to continue his career, and did so with spectacular success: he took charge of the London Philharmonic, the Orchestre National de France, appeared as guest conductor around the world, was named honorary guest conductor of the Israel Philharmonic. In 1991, he became music director of the New York Philharmonic for an 11-year tenure, the longest in the orchestra's history.

The Philharmonic, which dedicated its Saturday evening performance to Masur's memory, issued a statement that "he both set a standard and left a legacy that lives on today." The New York Times obituary spoke of Masur "transforming the orchestra from a sullen, lackluster ensemble into one of luminous renown."

However famous Masur was, it was only in 2002, in San Francisco, that he spoke of the fact that he had been a member of the Wehrmacht, the Nazi armed forces. It happened at an S.F. Conservatory lecture during the week of leading the S.F. Symphony in performances of Britten's War Requiem:

To illuminate the message of the War Requiem and its "fearful, desperate" opening, "the chorus unable to sing," stammering with "hopelessness," Masur spoke of being forced into the German army at age 17, there to spend the last three months of World War II. "I was in a company of 17-year-olds boys. We started out 130, we came back 27. This is not to describe my own fate — I am grateful because I survived — but to describe how deeply I am moved by the War Requiem," Masur said.

Masur was most celebrated for his interpretation of classics from Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler, Bruckner and Bach, but as his advocacy of the Britten Requiem, Janácek, Shostakovich and other more contemporary composers showed, he did not limit his repertoire. He has appeared in Davies Hall, both with the touring Dresden orchestra and leading the S.F. Symphony in 2009 in performances of Sofia Gubaidulina's The Light of the End. His last appearance here was in 2011 when he conducted Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Masur is survived by his wife, Tomoko, a Japanese soprano, and five children, including Ken-David Masur, the San Diego Symphony’s associate conductor.