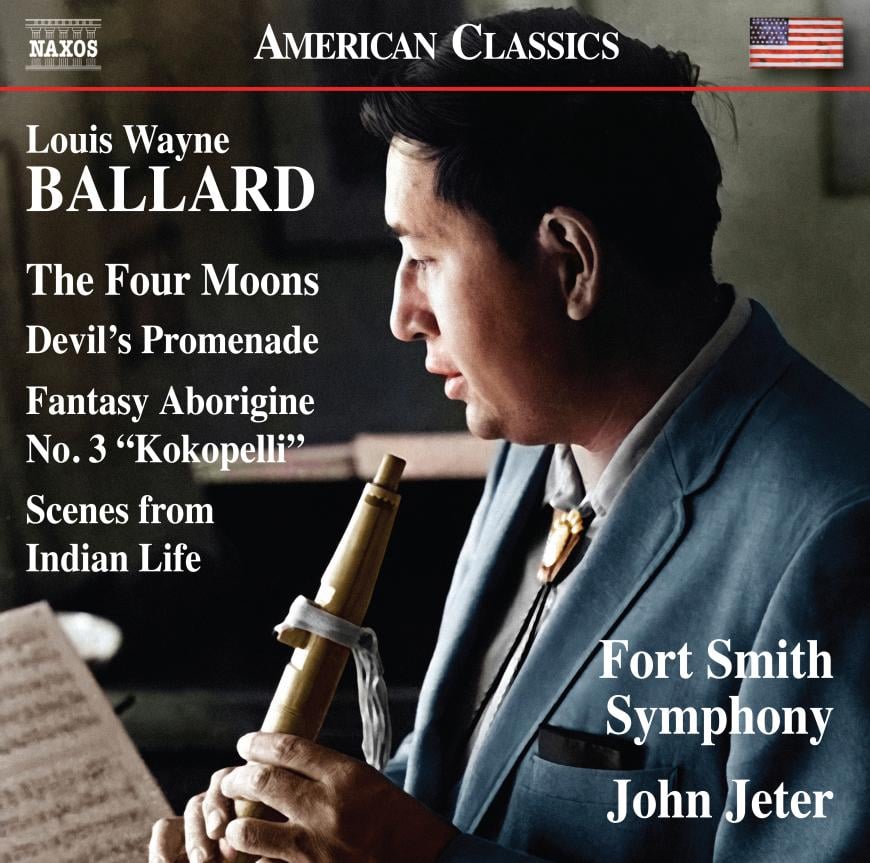

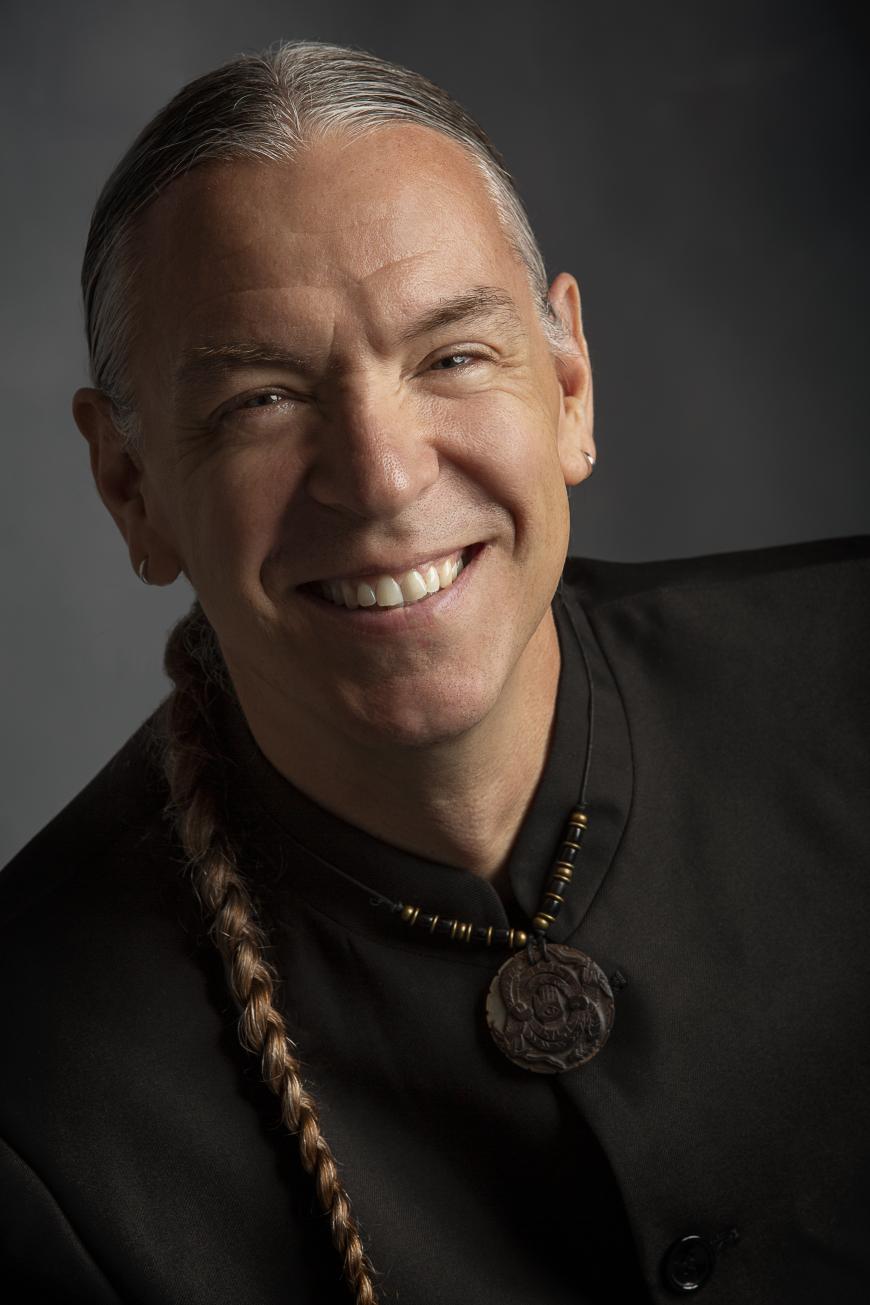

Whenever the definitive history of music by all of America’s pioneering classical composers is written, the recordings from the Fort Smith Symphony of Arkansas will play a prominent part. Under the visionary leadership of Music Director John Jeter, the Fort Smith Symphony has embarked on a groundbreaking series of recordings for Naxos that has now expanded beyond the orchestral music of Black American composers Florence Price (1887–1953) and William Grant Still (1895–1978) to embrace Native American composer Louis Wayne Ballard (1931–2007). On a new album, the first in what will hopefully be a series of Ballard releases on Naxos, Jeter presents the world-premiere recordings of four pieces that showcase the many facets of this composer’s artistry.

Ballard was born in Devil’s Promenade, Oklahoma, to a Cherokee father and Quapaw mother. Despite his initial indoctrination at a government-run Indian boarding school that encouraged assimilation, suppressed Native traditions, and whitewashed U.S. history, young Ballard continued to speak his Indigenous language and engage in tribal dances. After receiving degrees in music theory and music education, he attended the Aspen Music Festival for many summers and studied there with prominent teachers and composers. Even before becoming the first music teacher and then music director at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe (he would go on to serve as national curriculum specialist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs), he had begun to compose music that incorporated Native rhythms, themes, instruments, and storytelling into classical forms.

Ballard may not have been the first recognized Native American classical composer — that honor goes to Dennison Wheelock (1871–1927), an Oneida composer whose Aboriginal Suite was written for the 1900 Paris Exposition and premiered at Carnegie Hall earlier that year — but he is likely the best known. Devil’s Promenade (1973), one of the works on the new album, was commissioned by the Tulsa Philharmonic Orchestra and premiered under the baton of Skitch Henderson. Two years later, Ballard advocate Dennis Russell Davies conducted it at the Cabrillo Music Festival in Santa Cruz. The strongly rhythmic work calls for six different Native American percussion instruments and, in its middle section, incorporates a melody from a Sioux Ghost Dance.

The first three movements of Scenes From Indian Life (1963), which showcase Ballard’s humorous side, received their premiere from the Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra under Howard Hanson. After Ballard arranged the piece for elementary and advanced bands, he added a fourth movement. The San Jose Symphony under Leonid Grin premiered the completed work in 1995.

The album contains two other markedly different but equally strong and appealing compositions that demonstrate Ballard’s ability to integrate the ever-evolving classical music of his time with distinctly Native elements. The Four Moons (1967), a ballet written to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Oklahoma statehood, was danced by four Native ballerinas, each from a different Oklahoma tribe, in its premiere. As heard here, it calls out for restaging. Fantasy Aborigine No. 3, “Kokopelli” (1977), one of six Fantasy Aborigine works by Ballard that focus on the mythologies of different tribes and cultural areas, was commissioned by the Flagstaff Symphony and features a bevy of Native percussion instruments.

In a Zoom interview with Jeter and Oklahoma-based Chickasaw classical composer Jerod Impichcha̱achaaha’ Tate, Jeter explained that the recording project began after he told Tate that he wanted to record music by the first Indigenous concert composer in the United States. Tate said it had to be Ballard.

“Louis was a master orchestrator and a real trailblazer for Indian Country,” Tate said. “The fact that this recording has happened is really remarkable. I can’t fully express how truly important it is. Now I can point all of my American Indian composition students to this album on Spotify [so that they] can experience Louis’s music firsthand.

“Louis was a good friend and a very important person in all Native musicians’ and composers’ lives. He is similar to [Béla] Bartók in that he was an ethnomusicologist of his own people as well as a highly trained classical pianist and symphonic composer. Everyone in North American Indian Country knows and reveres him, but we didn’t have a recording until now.

“My grandmother attended The Four Moons’ premiere, and there are lots of folks still alive who remember his premieres and performances. That includes me. From 2006–2008 at the National Museum of the American Indian, Louis was part of a program entitled Classical Native. Lots of famous Native composers and musicians were there listening to and performing Ballard’s chamber works. I recorded and archived those performances.”

As the Naxos recording project took form, Jeter reached out to Simone Ballard, the composer’s granddaughter. Not only was she familiar with the several dissertations written about her grandfather’s works, but she also knew the condition of various unpublished manuscripts. As Jeter soon learned, Scenes From Indian Life was the only composition rentable from a music publisher. For Devil’s Promenade and The Four Moons, he worked with the Fleisher Collection in Philadelphia, which holds all of Ballard’s orchestral scores and parts, to create critical editions. And toward the end of the COVID lockdown, when staff was short, Jeter rapidly created a critical edition of Fantasy Aborigine No. 3 from the various parts he found in the collection.

There are, of course, many other notable compositions by Ballard. Incident at Wounded Knee (1974) was performed on an Eastern European tour by The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, who had commissioned it, and finally made it to Carnegie Hall in 1999. In 1977, Ballard composed a band piece for performance during the halftime of an NFL game between the Dallas Cowboys and the Washington Redskins.

“Band is a massive culture in Indian Country,” Tate explained. “For the halftime performance, there were auditions all over to create a 140-piece American Indian band. The halftime was opened by the Navajo National Color Guard. Louis also created the very first American Indian curriculum for public schools. He dedicated himself to discovering solutions for expressing Native identity in symphonic music. He was amazing, and we are all very familiar with his works.”

Tate and Jeter are quite optimistic about the future of Ballard performances and recordings. “We recorded the CD after playing everything in concert and performing a year’s worth of Ballard’s symphonic works, chamber music, and more,” Jeter said. “I’ve done a lot of interviews about Ballard that are slowly appearing. The CD has been played on BBC Radio 3 and by the Australia Broadcasting Corporation, which plays a lot of Fort Smith Symphony recordings. Sirius Radio’s Symphony Hall named it ‘album of the week’ in November, and reviews have appeared in Gramophone and other publications. The next phase, if the recording does well, is to have score and parts ready for another Ballard recording. There are six Fantasy Aborigine works, and we hope to record all six together. Each one is very, very different.

“We absolutely need to bring back Native voices to the concert hall. To have this really dynamic music coming from someone who isn’t related to the Austro-German tradition, except for some basic points of orchestration, adds so much variety to the repertoire. It would be wonderful if the Chicago Symphony were to open in Carnegie Hall with Devil’s Promenade. It’s music that would really blow people away.”

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify Simone Ballard’s knowledge of and relationship to her grandfather’s works.