Excitement about the 20th anniversary Music@Menlo Chamber Music Festival is clearly audible during a Zoom interview with Co-Artistic Director Wu Han from the Hudson River Valley home she shares with her husband and fellow founder and director, David Finckel.

A much higher standard of audio abounds on the so far 132 CDs preserving festival performances from the Music@Menlo LIVE label. For Wu Han and Finckel, who also take the stage on piano and cello, respectively, the audio standard befits the virtuosity of the performers engaged each summer, as well as the festival’s historically comprehensive mission of showcasing and recording chamber music from three centuries.

Returning to what Wu Han terms “a full festival, with all live audiences” on the Atherton campus of the Menlo School, this year’s festival, beginning on July 14, will focus on Franz Joseph Haydn, “the father of chamber music and the father of the string quartet.” Piloting both the recording of concerts and their distribution live over radio and the internet will be Da-Hong Seetoo, an engineer and producer known for the innovation and quality of his handling of sound.

Now in their 60s, Seetoo and Wu Han have musical affiliations dating back to growing up in China. One of Seetoo’s uncles was a music teacher of Wu Han’s sister in Taiwan, where the exiled government of Chiang Kai-shek allowed for study of Western classical music. On the mainland in Shanghai at that time, Seetoo’s father, who’d been principal second violin in the city’s orchestra, and his mother, a professor of piano at the Shanghai Conservatory, lost their jobs, instruments, and music under the dictates of the Cultural Revolution, begun in 1966 when Seetoo was 6. Both Western classical music and traditional Chinese music were proscribed by the communist government under Mao Zedong.

The Seetoo parents were sent to a peasant farm for “re-education,” and Da-Hong and his younger siblings were put under the care of their “working-class” nanny while attending elementary school and memorizing Chairman Mao’s “Red Book” of proclamations. After the parents were allowed to return to Shanghai, their instruction of their son in music and violin had to happen in secret with borrowed scores and recordings, and their pupil often had to practice with a mute.

Seetoo’s father unknowingly fostered a second career for his son by letting him tinker with a 1947 General Electric tube radio and a reel-to-reel Telefunken tape recorder, with which he could preserve the sounds of borrowed classical music LPs. “No one knew how to fix the recorder, and you wouldn’t want people to know you had it,” says Seetoo, in an interview from his Forest Hills, Queens, residence. “So I had to learn how to fix the belt and the bearings and how to splice tapes.” Listening to the recordings, “I had to reverse-engineer how these musicians would play things. I became very proficient at it, though because it was all done within a closed environment, I had no idea who I was as a musician.”

The first time Seetoo experienced classical music in person followed Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China and the slow thawing of relations with the West. The concertmaster of the visiting Philadelphia Orchestra struck up a friendship with another of Seetoo’s uncles, who was concertmaster of the Beijing Central Philharmonic, and Seetoo got tickets to a performance by the visitors. “I was blown away,” he recalls. “They played [Ottorino] Respighi’s Pines of Rome, and I thought they’d pull the ceiling down. It was life-changing.”

The Shanghai Conservatory resumed its earlier activities after Mao’s death in 1976 and the consequent conclusion of the Cultural Revolution. Seetoo, though only 16, found himself “much more advanced” on violin than his sister, five years older, whose study of the instrument had been stunted by four years on a re-education farm. This put the siblings in an uncomfortable competition for placement at the conservatory, which had few openings for many thousands of applicants. The conservatory’s curious solution was to have the younger sibling audition for a new, separate graduate program, effectively skipping five years of standard schooling. “My parents scrambled. They found me coaches to give me private lessons because I’d never learned anything about things like theory and music history,” says Seetoo. “But my memory at that point was so good that I apparently scored the highest amount in all the fields.”

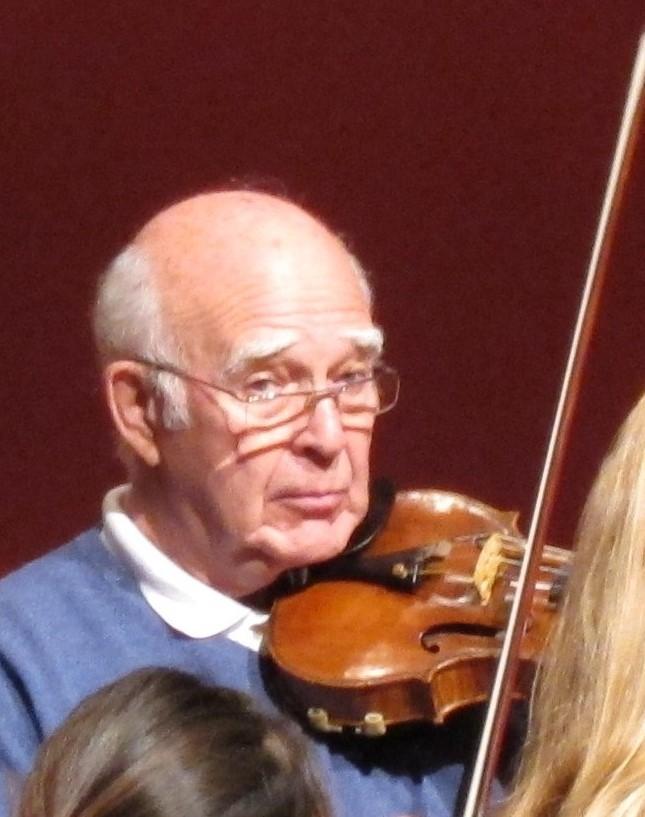

As Seetoo completed his first year of graduate education, his father pondered getting his son to the U.S. His own father had studied violin in Boston while pursuing a degree in engineering from MIT, and his wife’s father had gone to Harvard. During a tour by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to Shanghai in 1979, concertmaster Joseph Silverstein made a fortuitous visit to the conservatory. “The school called me and said, ‘We need you to be our window dressing,’” Seetoo recounts with a giggle. “I played for Silverstein, and he got very interested. He even showed me his ‘del Gesù’ [violin]. I barely spoke any English, but I got through most of the music things. And it so happens that Time magazine had a reporter documenting the visit, and my name was mentioned in print.”

The article caught the eye of Seetoo’s cousin Amy, who’d married an American and was living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She then effected a reunion between her father, one of the Taiwanese Seetoos, and Da-Hong’s father, who let his brother know about his hopes for his violinist son. Amy, fluent in English, wrote to both the Curtis Institute of Music and The Juilliard School, sending copies of her cousin’s recital tape. Juilliard refused on the basis of Seetoo’s unavailability for an in-person audition. But the director of Curtis, John de Lancie, had himself attended the school with Silverstein, and he spoke with his fellow alumnus about the Time article and its favorable mention of Seetoo. “Joseph said, ‘Take him, he’s good,’” notes Seetoo. “And a week later I got a telegram from de Lancie, accepting me on a full scholarship to study with Ivan Galamian. I couldn’t figure out the telegram, but my parents spoke English.”

Seetoo’s scheduled start at Curtis in the fall of 1979 was delayed by his obligatory representation of China at the Sibelius Violin Competition. “If I’d won, my government would have retained me,” he points out. But he didn’t, and they didn’t. With lessons from Galamian at Curtis beginning the following January, Seetoo learned regimen as well as technique. “He was very, very disciplined and made me feel I was so damned undisciplined.”

In the summer of 1983, Seetoo and Wu Han’s paths crossed in line for registration at the Aspen Music Festival and School. “I heard someone call his name and thought, that was my sister’s teacher’s nephew,” recalls Wu Han. “So we made friends and went for Chinese food.”

“I said, ‘What do you play?’ and she said, ‘Piano,’” remembers Seetoo. “So I said, ‘Let’s read something together this afternoon.’ The girl was amazing, she could sight-read anything, holy moly!”

“He was one of the most intense players, with the best ear and perfect pitch,” adds Wu Han. “And at Aspen, he was assistant concertmaster in the Festival Orchestra.”

Wu Han became aware of her new friend’s technological side when she accompanied him to pick up a shipment of electronic equipment at a local Fed Ex. “He said, ‘I ordered this so I can build a receiver to listen to any signal in the world, including news from China.’” She later learned, from some of Seetoo’s fellow Curtis students, that he had produced audition tapes for them and that “all the teachers there, from Gary Graffman to Joey Silverstein, wanted to give Da-Hong extra lessons because, when they brought this Chinese kid to their house, he’d fix everything, from toasters to refrigerators to car batteries. He knew how to take apart and build things.”

Wu Han herself had been “always very interested in gadgets,” and when she began to date cellist David Finckel, she found him similarly inclined. Finckel had been involved with the Emerson Quartet since 1979, and after marrying Wu Han in 1985, the couple lived in the New York area, not far from Seetoo, who’d begun violin study with Dorothy DeLay at Juilliard the previous year. Seetoo helped them set up their home stereo system, a task for which he continues to be flown around the country and paid well by those who can afford him.

By the time of his graduation from Juilliard, Seetoo was concertizing but also working part-time at the Stereo Exchange near Union Square in Manhattan. “I went to pick him up there for Chinese lunch,” says Wu Han, “and he was in the repair department with an apron on and all the engineers in the store standing in line for him. He was the guru of the store.”

Ultimately, says Seetoo, “I came to the realization that I just hated the lifestyle [of a virtuoso soloist]. … You have to make good to all the sponsors and presenters, to kiss up to them, and the worst part is, you have to fly almost every day. I wanted to have a family and have children and see them every day.”

Forming a lucrative full-time job out of his longtime love of recording technology was relatively easy for Seetoo. Finckel and the Emerson Quartet had been recording for Deutsche Grammophon with in-house engineers and producers, “but it became more and more evident that they wanted me to get involved [as engineer and producer, as of 1988], just because I happened to have been a fiddle player,” says Seetoo. His work with Emerson and DG would result in the Quartet’s 2001 Grammy for Best Chamber Music Performance and Seetoo’s own 2006 Grammy for Best Engineered Album, Classical. Seetoo’s 1996 recording of Wu Han and Finckel performing Grieg, Schumann, and Chopin sonatas became a covermount for BBC Music Magazine and the inspiration for the launch of the couple’s independent ArtistLed label, which Seetoo continues to serve.

“Da-Hong enabled us to realize our dream,” says Wu Han. “He’s not only a great friend and devoted engineer but also a very stable force in terms of guidance. Both David and I are high-strung personalities, we go for it and never stop, and Da Hong is the one who says, ‘Here’s what I think.’ He doesn’t beat bushes; he doesn’t like small talk. It’s rare in your life when you have a friend you can depend on, always telling you the truth.” She recalls an early memory of his listening to her playing Beethoven’s “Spring” Sonata. “He’d say, ‘Wu Han, your second B and the third note are not together, and on the fourth C you’re using the wrong fingering.’ I’d say, ‘What are you talking about?’ and then realize, ‘He’s right!’”

Seetoo clearly links his worth as engineer and producer to his earlier training and achievement as a top-flight instrumentalist. “To be a good musician is not only a prerequisite to becoming a recordist, it’s a must,” he insists. In working with musicians, “I have their trust, because they know everything I’m asking about is music-related. I have empathy for what they go through. I know what it’s like to stand in front of a microphone, as well as to be working behind it.”

He’s also established a legendary knack for taking apart and refashioning microphones to particular purposes. Designers of mics “put mechanical and electronic filters in this cage-like thing, and the cage becomes a resonating chamber,” Seetoo points out. “You want the sound to escape, you do not want it to hang around, doing all sorts of funky things which are uncontrolled. That’s why I have to go in there and get rid of stuff. My own microphones are nowhere near as ‘universal,’ but they make a much better sound.”

In like manner, Seetoo also retrofits speakers, preamplifiers, amplifiers, and other recording equipment. Although he “never set foot in a recording studio to get proper professional training,” he’s persistently researched the evolution of recording over his lifetime, from analog to DAT (digital audio tape) to computer-based technology. “If you go to Da-Hong’s house,” Wu Han reveals, “by his toilet is a stack of stereo system and computer manuals. He reads them front to back.”

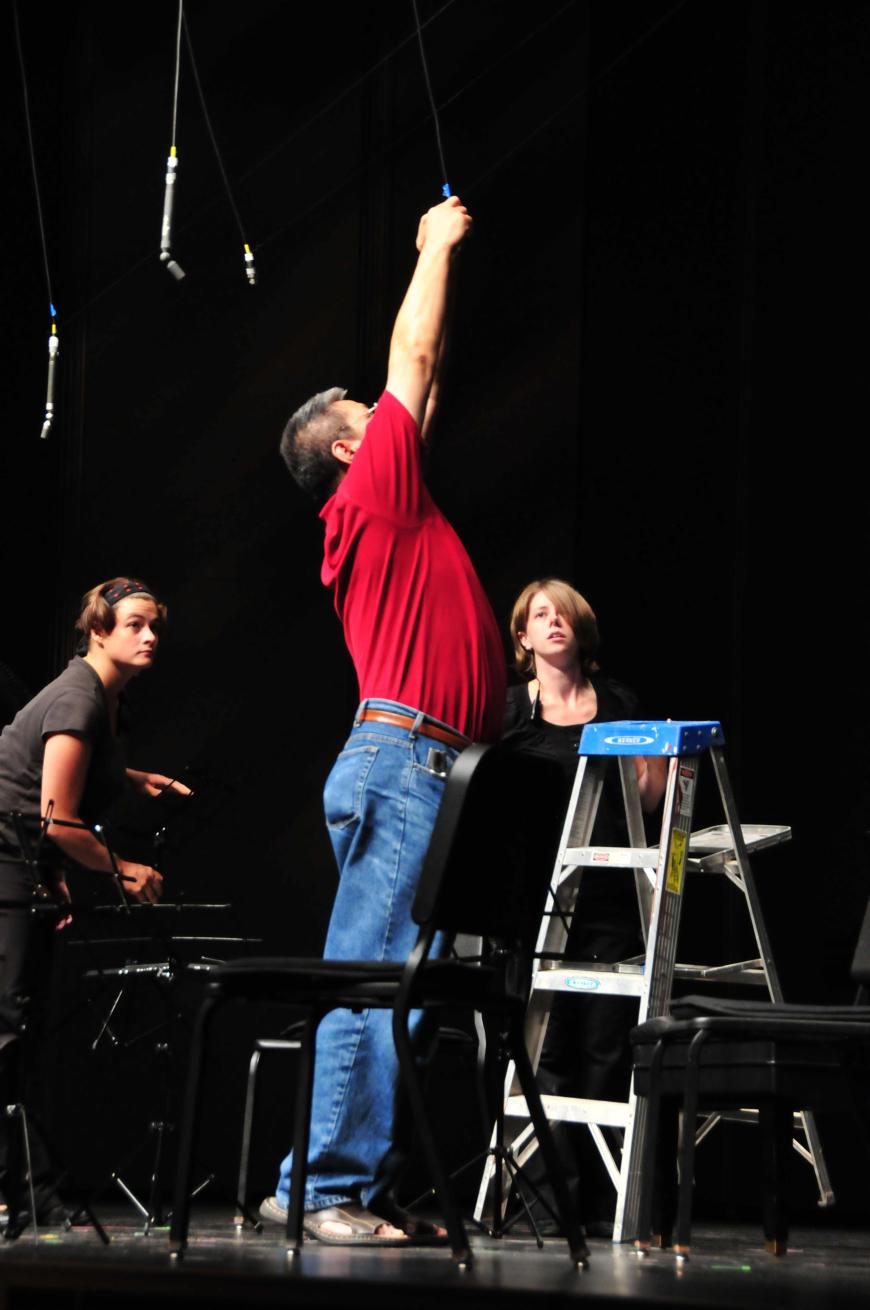

Finckel and Wu Han took Seetoo out to California when they co-directed La Jolla Chamber Music Society’s Summerfest in 1999 and brought him to their launch at Menlo three years later. With the variety of ensemble size at Menlo, the positioning and selective mixing of microphones was paramount. “We decided from day one that the microphones would be hung from the ceiling, covering the whole stage with all conceivable configurations,” says Seetoo. “So I record every microphone into its own separate track, and in mixing, a lot of [those] tracks I am not going to use. If I need to, I can put up a couple of stands.” When San Francisco Conservatory of Music-trained trombonist Matt Carr was brought in as Seetoo’s sole assistant, Carr said to Seetoo, “‘You don’t even move your microphones!’ At first, he was very disappointed.” Now familiar with Seetoo’s system, Carr records the festival’s student concerts.

Seetoo is still somewhat resistant to travel. His wife, oncologist Margaret Chen, and their children, Stephanie (19) and Leon (17), are busy on the East Coast and won’t be able to keep him company at Menlo, as they sometimes do. But he still looks forward to rejoining his friends, with whom he also collaborates, closer to home, at The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. “The reason I first said yes to David and Wu Han about Menlo is because I knew how important they’d place the recording of the festival,” says Seetoo. “And it’s crazy how much stuff we’ve done.”

“I think this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Da -Hong, as an engineer, to make a statement,” says Wu Han. “This is establishing a chamber music library in the most extensive way. And if we didn’t do this project, there would be a whole generation of our living musicians who would completely disappear from music history.”