June 12 at Davies Symphony Hall will be the time and place for the U.S. premiere of Oscar Peterson’s The Africa Suite, a posthumous work planned by Peterson’s widow, Kelly, and arranger John Clayton, who compiled the music. As part of SFJAZZ’s 41st San Francisco Jazz Festival, the evening will serve as an overall tribute to Peterson, the titanic pianist and composer who died in 2007 at the age of 82.

Peterson never heard the suite performed, though he did record a few of its sections: “Nigerian Marketplace” (the title track of a 1981 Pablo Records release), “Peace for South Africa,” “Hymn to Freedom,” and “The Fallen Warrior” (written for Nelson Mandela). Clayton, speaking from New York, where he’s been working on a separate Carnegie Hall commission, recounted a phone call from Kelly Peterson after her husband’s death.

“She said, ‘I have all these pieces Oscar was trying to put together for The Africa Suite, and a lot of it is incomplete. Would you mind finishing it up?’ And I thought, oh man, there’s no pressure there, having Oscar’s spirit looking down on me and saying, ‘That’s not what I was thinking of.’ But I went ahead and did the best I could, trying to get into his brain, which I’ve been doing since I was 16 and heard a record he’d done with [bassist] Ray Brown and [drummer] Ed Thigpen.” As a young bassist, Clayton followed Brown closely, in the process memorizing all of Peterson’s compositions “with the dream of one day possibly joining [the pianist’s] trio.”

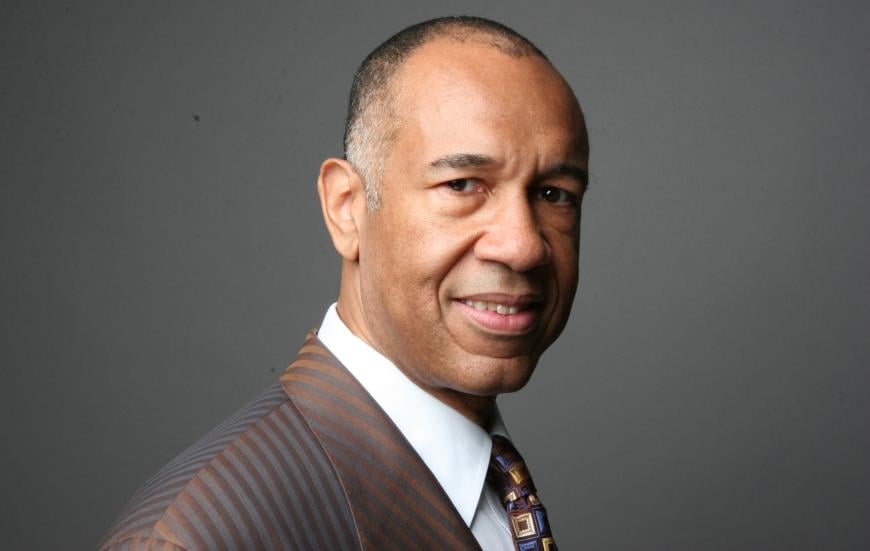

That dream was never fulfilled, but Clayton, now 71, went on to tour with the Monty Alexander Trio and the Count Basie Orchestra, sometimes sharing bills with the Oscar Peterson Trio. Clayton also served as principal bassist of the Amsterdam Philharmonic before returning to California and co-founding the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra with drummer Jeff Hamilton in 1986.

Clayton became friends with Kelly Peterson after her marriage to Oscar in 1990. To assemble The Africa Suite, she supplied Clayton with “as many of the materials as she could,” the arranger said. “But there were only recordings, no scores at all, and most of it was not at the piano. There were synthesizers and electronic keyboards that he was using.” Peterson felt these expanded his acoustic palette.

“There were some things I couldn’t use,” Clayton continued. “I just dealt with each part separately, tried to complete them if they weren’t completed. He might have done some improvising [in one section], and I’d think, this is great thematic material that would satisfy the need for a bridge. Then I’d try to realize it in the large-ensemble context. I’d think about Oscar’s normal programming, since I’d listened to his live shows for so many years. He’d often start with something full and big, take it on to various moods, and bookend it with something up-tempo.”

The world premiere of The Africa Suite — in February 2020 at Koerner Hall in Toronto, Oscar and Kelly Peterson’s longtime city of residence — was experienced “with overwhelming acceptance and excitement,” Clayton said. “All of Canada knows about Oscar; his face is on a coin.” The Oscar Peterson International Jazz Festival Orchestra was joined by bassist Christian McBride, drummer Lewis Nash, and Berkeley, California-bred pianist Benny Green, whom Peterson had dubbed his protege. Green will be featured again at the Davies premiere.

“Oscar telephoned me in the winter of 1992 to tell me that the Glenn Gould Foundation was giving him an award for excellence in music and communication,” explained Green from his Berkeley home. “Part of the award entailed him choosing a younger artist to receive a protege prize. Man, I was elated and also shocked. I told Oscar directly, ‘There are pianists who have a lot more chops than me and know a lot more of your verbatim vocabulary than I do.’ But he really believed in me.”

Green, now a perennially youthful 61, started classical piano at age 7 with teacher Claire Shallit, who soon advised his parents, “You should try to find a jazz teacher for Benny because he likes to improvise.” He was cultivated in the bumper crop of future jazz luminaries at Berkeley High School in the 1970s and ’80s and gigged locally as a teen with trumpeter Eddie Henderson and vocalist Faye Carol. “She really made me find a home for myself inside the blues,” Green said of Carol. “And I wouldn’t have been able to pass my [1983] audition for [vocalist] Betty Carter if not for everything that Faye gave me.”

After relocating to the East Coast and accompanying Carter, Green recorded and performed with the likes of Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard, Houston Person, and Ray Brown, building a reputation as an imaginative and energetic interpreter and improviser as well as a supportive listener. This approach to the keyboard and Green’s work with his own small ensembles in the early 1990s naturally bonded him to Peterson.

“I think it’s gotten framed that I sat down and had structured lessons with Oscar, but they weren’t really called ‘lessons,’” said Green. “Once he sat me down at his left at the piano and said, ‘I’m going to show you “flat” playing,’ and he played a B-flat blues which didn’t feel like Oscar playing. It was really awkward for me. And just as I was about to get out of my seat, he said, ‘Now I’m going to add accents,’ and all of a sudden, it was Oscar. Another time, he gave me a mini-seminar on playing a ballad, and he took his time describing this choreography: Play a chord, now a connecting run, an arpeggio, and now a melody. It was a tremendous, unspeakable honor for Oscar to care enough about me to be friendly and share his sincerity.”

At the same time, “he wanted me to be my own artist,” Green said, “and I know for a fact that he didn’t want me to feel like he was breathing down my neck. I’ve never really thought of defining the artist I am by one singular influence, and I love two pianists who, on the surface, in terms of their styles, are polar opposites: Oscar Peterson and Thelonious Monk. Oscar himself said to me, ‘Every time I play, I endeavor to pay homage to three gentlemen, not that I’m always successful: Art Tatum, Nat King Cole, and Henry “Hank” Jones.’ I can listen to eight or 16 bars of Oscar and know it’s Oscar but hear something of all three of those guys.”

Clayton’s arrangement of The Africa Suite showcases the breadth of Peterson’s artistry across nine named sections, which Clayton, who is bringing his 22-piece Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra to Davies, described. “‘Night Cry’ starts with drums and percussion, which go until we get into predictable swing — because if it’s Oscar, it’s going to, at some point, swing. For ‘Ellington Looks at Africa,’ I tried to think [Duke] Ellington in terms of the orchestration of saxophone and brass. ‘Night in Transvaal’ has an ostinato bass line that goes through, and it almost sounds TV theme-ish, with French horns playing a sort of Lalo Schifrin background. ‘Peace’ has a very brief brass introduction, then goes into Benny Green playing the melody, and we give Benny a chance to really explore before we bring in the rest of the orchestra.

“For ‘Nigerian Marketplace,’ I had to learn how to play the melody because it’s an ass-kicker [with rapid arpeggiation, vibrato, and extensive fingerboard work]. Although it’ll be Bob Hurst on bass, I’ll be standing in front waving my arms. ‘Tribal Dance,’ as you’d imagine, starts with a village vibe. I’ve got the entire orchestra doing notated handclaps, ending with a bass solo, and thematic melodic material featuring woodwinds and a baritone sax playing the melody. ‘The Fallen Warrior’ is typical Oscar, a beautiful melody reflecting some of the melodic sequencing you would have found in his bebop background. ‘Soweto Saturday Night’ is kind of a medium-swing groove, something Oscar would have done for his trio, big and bold, kind of ‘going home.’ But then, we calm everything down by performing ‘Hymn to Freedom,’ and that’s just how Oscar would do it all by himself. The piano has already set the mood, and I bring the orchestra in, as pretty as we can play, the French horns working together with the trombones to give really warm underpinning, and [there are] woodwinds and flugelhorns for a larger, rounder, deeper, darker sound.”

The tribute concert will open with pianist Gerald Clayton, John’s son, playing Peterson songs in trio contexts. “We’re covering three periods of Oscar’s piano career,” noted the elder Clayton. “Number one with guitar [Russell Malone] and bass [Clayton]. Then with bass [Clayton] and drums [Hamilton]. And then the unbelievable, beautiful work with solo piano [Green].” In another trio setting, pianist Kenny Barron will be partnered by Malone on guitar and Hurst on bass.

In the second part of the program, the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra and its pianist, Tamir Hendelman, will be showcased in Clayton’s arrangement of several sections from Peterson’s Canadiana Suite, recorded by the composer for Limelight Records in 1964.

And then The Africa Suite. Céline Peterson, Kelly and Oscar’s daughter and a producer and artists’ representative, will be present with her mother at Davies for the premiere. Green attested: “All listeners — and that includes myself — should be looking to The Africa Suite to show us some beautiful and deep things, things [we] can feel and appreciate and respect and reflect on and maybe be changed by. It presents a glorious and victorious sweep of emotions. Show us your open window to Africa, Oscar Peterson.”