The year was 1968, and Stanley Kubrick was putting the finishing touches on his now-classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Dissatisfied with the score Alex North had composed for the science-fiction epic, the director decided to discard it, opting to leave in the classical music he has been using as an aural placeholder.

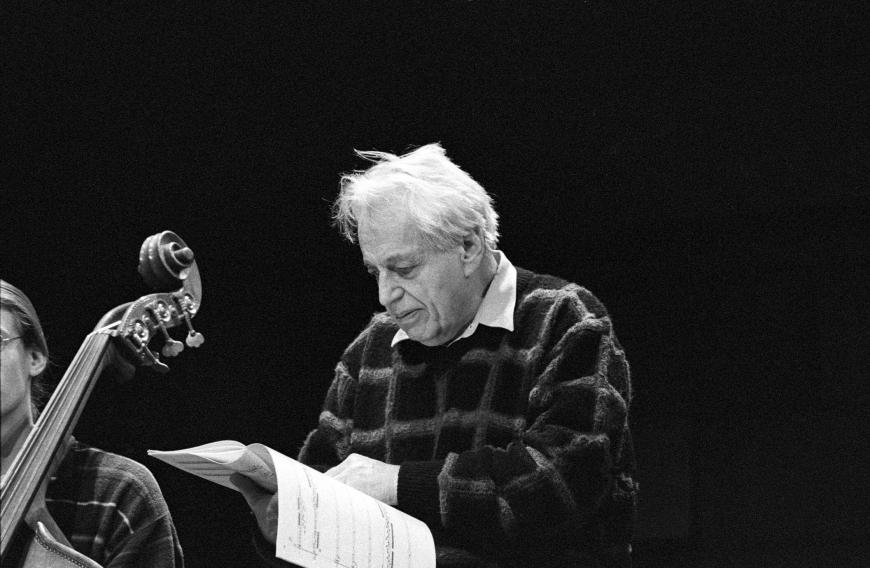

Thanks to that highly unorthodox, last-minute decision, millions of people were introduced to the avant-garde yet approachable music of György Ligeti (1923-2006).

The film utilized four of Ligeti’s works, including the Kyrie movement from his Requiem, which became a sort of leitmotif for 2001’s mysterious monolith. While the composer was initially (and understandably) miffed at Kubrick for using his music without permission, the film proved to be the perfect vehicle for a first encounter with these challenging works.

“With a piece like Atmospheres or Lux Aeterna, which is also used in that movie, there is a sense of vastness that comes from the way he uses the orchestra, or, in the choral piece, the limits he’s asking for from the choir,” said musicologist Ben Levy of UC Santa Barbara. “There’s always a point in Lux Aeterna that I forget these are human voices producing this sound.

“In that way, it’s very appropriate for a movie like 2001, which asks questions about what it means to be human, and how to think about the place of mankind in the universe. This music relates nicely to what Kubrick is doing, in that it offers you a glance into the abyss.”

Others have heard something similar in Ligeti’s music — composer Thomas Adès once suggested it depicts “the heat-death of the universe.” But that description ignores its absurdist sense of humor, as well as the sheer joy of his immense creativity.

The centenary of his birth, on May 28, provides a great opportunity to expand our understanding of Ligeti’s music, which continues to entrance both listeners and performers 17 years after his death. A lot of avant-garde music holds little interest once its initial shock value inevitably fades. Ligeti’s, in contrast, keeps being mined for more insights, more emotional nuance, more depth.

“It looks and sounds like no other music,” said pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, the composer’s friend for two decades and the man who premiered many of his piano pieces. “He was too creative to fold into a system.”

“He fashioned a striking new musical language, using — on the face of it — very traditional means,” added pianist Danny Driver, who recently recorded a new CD of Ligeti’s Etudes. “It’s just 10 fingers and feet on the pedals. Yet there’s something so arresting and fresh and ear-opening about it.”

Ligeti wasn’t a member of any school of composition, and he didn’t spawn a lot of imitators. It’s fair to call him sui generis. Conventional wisdom suggests this reflects his brutal adolescence and young adulthood, during which he was persecuted both by the Nazis and, later, the Communists. After those scarring experiences, he was immune to rigid ideologies, in either politics or music.

“Being a Hungarian born in Romania, being a Jew discriminated against in Hungary — these experiences shaped his self-image as a minority figure,” said Levy. “But it’s also something he cultivated [as an] image: Ligeti as the perpetual outsider.”

That outsider status was very real — even life-threatening — during his early years. Born into an ethnically Jewish Hungarian family living in Transylvania, he was arrested in 1944, while studying at a conservatory, and sent to a forced-labor camp for the remainder of World War II. His father and brother were both killed in the Holocaust.

“He always carried this tragic dimension in him,” recalled Aimard. “He said the deaths of his father and brother never left him. He carried a kind of [survivor’s] guilt inside him until the end of his life.”

After the war, he arrived in Hungary, where he completed his studies and then taught at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest. But he did not feel welcome or comfortable under the nation’s Stalinist regime. Ligeti faced both intense anti-Semitism and the deep-seated conservatism of the nation’s musical establishment. He wrote some notable music in this period, but performed it only in private.

He fled Hungary during the 1956 uprising, immigrating to Vienna, where he found freedom and struck up relationships with like-minded composers, including Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. But he found their adherence to certain dogmas stifling and was unafraid to make his own way.

“His music explores all the new techniques and structural ideas of the Western European avant-garde,” said Lisa Cooper Vest, a musicologist at the University of Southern California. “But it does so in a way that invites the audience to connect to it. Some of the other avant-garde composers were not interested in that.”

Vest and her husband Matthew Vest incorporated two of Ligeti’s piano pieces into their wedding ceremony, including one of his 18 Etudes for piano. Among his best-known works, these concentrated, highly imaginative works were initially seen as almost unplayable (a notion Aimard disproved in the 1990s). Today, at least a few of them are part of many world-class pianists’ repertoires, including Yuja Wang.

“I find a great warmth and humanity about them,” said Driver. “He was a great melodist. You can feel the legacy of Chopin and Rachmaninoff as you play them. There are also clear compositional connections to Debussy.”

That said, this music is, for the most part, anything but placid. A lot is often happening at once.

“The way he uses polyrhythms — it’s not so much finger-breaking as brain-splitting,” Driver said. “In the Etudes,sometimes he has the left hand on the black keys and the right hand on the white keys. It’s an entirely different way of playing the piano. The two sides of your body are no longer working together in a conventional sense. It’s a very different way of imagining piano texture, and it yields very interesting harmonic effects.”

To some degree, this reflects the unusual way Ligeti composed his piano music. Although he was not by any means a virtuoso pianist — he could never play his own mature works — he would sit down at the piano, lay his hands on the keys, and commence what he called “a feedback loop” between musical idea and tactile-motor sensations.

Driver believes that greatly impacted his writing. “One does feel it while playing these pieces,” he said of the Etudes.“For all their difficulties, they are exquisitely written for the piano. He composed them with a great awareness of how hands operate and what is possible.”

“There are examples where you can imagine him sitting at the keyboards, getting ideas, and running with them,” agreed Levy. “There is one etude (No. 3) subtitled “Blocked Touches,” where one of the hands presses certain keys silently and holds them down. The other hand runs across patterns that cross those keys — but because those keys are pressed down, they don’t produce any sound. So there are hiccups to the flow — unpredictable rests.”

Of course, a lot of Ligeti’s music is unpredictable, thanks to the many and varied stylistic influences he incorporates.

“He’s a composer of synthesis,” said Vest. “He’s bringing together a lot of different things, including other musical traditions. You feel them working together in a structure that does not feel polemic.”

“He could relate in his mind a moment in Gesualdo, a late Renaissance composer, to a moment in Bruckner, to one created by a Central African horn ensemble,” Levy said. “He related them in his own imagination and responded to them with his own compositions.”

Ligeti also credited a huge range of nonmusical influences, from the paintings of Paul Cezanne to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. He was writing early sketches for an opera based on the classic children’s book — reportedly his favorite as a child — when he died.

“He had a taste for the absurd,” recalled Aimard. “He has written nonsense madrigals. His dark humor was very Eastern European. It’s a way to survive.”

The closest literary analogy to his music might be the plays of Samuel Beckett, which similarly placed tragic and comic elements in close proximity. “I think he would agree with Beckett that we live with existential horrors, but we need to get on and make the best of it while we can,” said Driver. “His opera Le Grand Macabre deals with just that. It’s tragic on the one hand, but comical on the other. There is that darkness, and also hope.”

Ligeti’s best-known orchestral piece is Atmosphères, a 10-minute-long soundscape that Blair Sanderson of the All Music Guide calls “essential listening for anyone interested in modern orchestral music.”

“All through that piece, you have these clusters — every note of the chromatic scale being played by some instrument of the orchestra, for octave upon octave,” said Levy. “Sometimes he’ll use different parts of the orchestra to emphasize certain notes within that. For instance, the pentatonic scale — all the black keys of the piano — will arise from that. The instruments carrying those will crescendo, while the others will decrescendo. Then they’ll switch places. Or families of instruments will come to the fore: The strings will crescendo while the brass and winds decrescendo, and then they’ll switch places.

“There are sections where the brass players blow through their instruments without producing notes,” he added. “They just produce the sound of wind passing through the instrument. That sort of noisy sound pushes the envelope of these closely spaced harmonies. It’s another way of introducing noisier elements into the sound, as opposed to a nice, pure orchestral tone.”

The results are often disconcerting, but also strangely compelling — so much so that both Levy and West point to it as a great introduction to Ligeti’s music.

Another excellent entryway is Driver’s new recording of the Etudes, which is slightly slower overall and generally more lyrical than Aimard’s recordings from three decades ago.

“The performing style of new music in the 1970s and ‘80s was dominated by an anti-romanticism,” Driver said. “Aesthetically, I think we’ve moved away from that. In this more open landscape for contemporary music, it’s possible to see these pieces in a different light. There is a palpable sense of tragedy in some of the etudes, while others have a lightness and humor and sort of pizzazz.”

But while he’s comfortable with his more relaxed approach, Driver adds that his interpretations will continue to evolve. “They are great, great compositions,” he said, “and thus they’re open to different readings.”

Aimard said his interpretations also continue to grow as he finds new things in the music, but he feels extremely fortunate enough to have received his initial instructions straight from the creator. Ligeti, he noted, was not hesitant to say what he wanted: On several occasions, he came up onstage at the end of one of Aimard’s recitals and instructed him to play one of his works again — only faster.

“He loved to challenge people — to push people to their borders,” Aimard said. “He did that with himself and his pieces. He was a marvelous, and very generous, friend. I feel it’s my responsibility to transmit the meaning of the music to the younger generation. I take that very seriously.”

Aimard played a short Ligeti piece as an encore after his recent performance of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto with the L.A. Philharmonic. He is devoting much of this year to playing Ligeti’s music, with upcoming performances in Berlin, Salzburg, and New York City.

Levy is also having a busy year: He just presented a paper on Ligeti’s world-music influences at a conference in Europe. But as he knows from personal experience, there are some aspects of the composer’s genius that can’t be fully expressed in words.

“When I was in graduate school and thinking about potential dissertations, I was asking myself whether Ligeti’s music was too cloistered away in the intellectual realm,” he recalled. “I was watching the movie 2001 on television. My cat was sitting on the couch.

“The scene scored with the Ligeti Requiem came on, and the cat, who had been sleeping, pricked up her ears and bolted across the room. That helped me to realize that there’s something in his music that operates on a very physical, visceral level, as well as an intellectual level. It operates on a gut level of immediacy.”

Driver concurs with Levy’s cat. “Ligeti’s compositions arise out of a tactile dimension,” he said.

“In a sense, he was exploring where art and the natural sciences merge. There is a great mind at work that reveals itself in the music.”