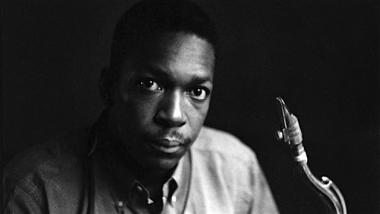

John Coltrane’s life is often portrayed as a hero’s journey, an epic spiritual quest to master and then transcend musical conventions in pursuit of higher planes of consciousness. As a neat narrative device this account is truer than not, emphasizing Coltrane’s ceaseless devotion to experimentation and his blithe disregard for the commercial consequences of his creative choices. But a new box set offers a broader and richer portrait of the protean artist, capturing the tenor saxophonist not as a solo seeker but as colleague embedded in an extraordinary creative community.

Released by Craft, Concord’s reissue imprint for its vast and invaluable catalog of seminal indie jazz labels (particularly Riverside, Contemporary, Prestige, Pablo, and the original Concord Jazz), Coltrane ’58: The Prestige Recordings is a beautifully produced five-disc set that contains every session Coltrane recorded for the dogged hard bop label in that crucial year, sequenced in chronological order. Produced by Oakland’s Nick Phillips, Coltrane ’58 is also available via streaming and on eight 180-gram LPs, with both physical sets featuring booklets with extensive liner notes by Coltrane scholar Ashley Kahn and historic photos.

Released by Craft, Concord’s reissue imprint for its vast and invaluable catalog of seminal indie jazz labels (particularly Riverside, Contemporary, Prestige, Pablo, and the original Concord Jazz), Coltrane ’58: The Prestige Recordings is a beautifully produced five-disc set that contains every session Coltrane recorded for the dogged hard bop label in that crucial year, sequenced in chronological order. Produced by Oakland’s Nick Phillips, Coltrane ’58 is also available via streaming and on eight 180-gram LPs, with both physical sets featuring booklets with extensive liner notes by Coltrane scholar Ashley Kahn and historic photos.

Most fundamentally, the project imposes order on a body of work that was introduced haphazardly and only grew more tangled over time. Not only did Prestige release albums with tracks from different sessions, the material often reappeared on albums with different names over the years. One session, from July 11, 1958, ended up scattered across eight different LPs. With many artists this would be a mere annoyance, but Trane’s rapid, sometimes month-to-month conceptual leaps are best understood as a thoughtful process of trial and experimentation. By the time of his death at the age of 40 in 1967, he’d packed at least six major creative chapters into a 12-year run.

“Ashley Kahn alludes to this in the liner notes. There were so many different Coltranes it could be really confusing,” says Phillips, who spent decades working for Concord Jazz, first in its namesake city under the founding owner Carl Jefferson and later at Fantasy in Berkeley after the label was acquired by a consortium including television producer Norman Lear.

Coltrane’s fans often didn’t know what to expect from his albums. In 1960 Atlantic released his label debut Giant Steps, an album that marked an apotheosis of chordal improvisation, and the following year Prestige issued Lush Life, featuring pieces he recorded in 1957–58 that documented his sound several paces earlier. “My Favorite Things comes out in 1961 and you have Prestige releasing other things from 1958 that year,” Phillips says. “It’s kind of all over the place. Listen to any individual Prestige album and the music is great music, but there are different things from different sessions. The idea here was going deep rather than wide so you get a sense of how rapidly his style evolved.”

Born and raised in North Carolina, Coltrane moved to Philadelphia after high school and started working as an alto saxophonist. He played in a Navy band just after World War II, and by the time he joined Dizzy Gillespie’s shortlived bebop big band in the late ’40s, Trane was playing tenor. Stints with altoists Earl Bostic and Johnny Hodges kept him busy in the early ’50s, but it wasn’t until Miles Davis hired the journeyman in 1955 for his first great quintet with pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones that Coltrane first gained national attention. There were half a dozen tenor saxophonists who would have been a more obvious choice, but Davis heard something in Coltrane’s sound and approach that appealed to him.

The quintet recorded prolifically for the next two years, but Trane’s increasing unreliability led Davis to kick him out of the band in 1957. Back at home in Philadelphia, he kicked his addiction to heroin and experienced a spiritual epiphany that changed his life and came to play a central role in his music. He started recording his own albums for Bethlehem, Savoy, and Prestige, but the key point in his development was a long engagement with Thelonious Monk’s quartet at the Five Spot in 1957. Rejoining Davis’s band in 1958, Coltrane played with such ferocity that the trumpeter often had no choice but to stand back and marvel, which is where Coltrane ’58 picks up the story.

The set opens with a blast of brilliance as Trane fully excavates Billy Strayhorn’s signature ballad “Lush Life,” building exquisite tension over nearly 14 minutes with trumpeter Donald Byrd, drummer Louis Hayes, and his fellow Miles Davis bandmates Paul Chambers and Red Garland. Like all the Coltrane ’58 material, the Jan. 10 session was recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s storied home studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, which also served as a home base for Blue Note Records. The most notable pieces here are a bright blues by a then-unknown 19-year-old Philadelphia pianist named McCoy Tyner, “The Believer,” and the Latin-tinged “Nakatini Serenade” by trumpeter Cal Massey, another close associate of Trane’s from Philly.

Something of an anomaly, the Feb. 7 session was released in its entirety eight months later as Soultrane. Featuring a quartet with Garland, Chambers, and drummer Art Taylor, it’s the session that inspired Ira Gitler to memorably dub Coltrane’s torrential approach “sheets of sound,” particularly his turbocharged workout on Irving Berlin’s “Russian Lullaby.” The rendition is guaranteed to keep the baby awake, while later ballads like a sumptuous 10-minute version of “Stardust” and an exquisite take on “Time After Time” captures Trane’s poised lyricism (and then there’s his prescient bossa-anticipating rendition of Ary Barroso’s “Bahia”).

“Looking at 1958, what resonates for me most is the contrasts,” Phillips says. “Listen to the velocity on ‘Russian Lullaby’ and ‘Lover Come Back to Me,’ and contrast that with his heartfelt, really melodic playing on ‘Stardust’ or the duet with Kenny Burrell on ‘Why Was I Born?’ He’s such a multidimensional player.”

The subtext of Coltrane ’58, what’s not directly on the album, is what Trane was doing when he wasn’t recording for Prestige. The biggest gap between his sessions spans July 11 to Dec. 26. During that time, he was performing widely with the Miles Davis Sextet. The band had recorded the epochal album Milestones just before Trane’s second and third sessions and made the classic live album Jazz at the Plaza Vol. I on Sept. 9 (both for Columbia). He was still performing occasionally with Monk, and recorded a seminal but underappreciated album with influential composer/arranger George Russell, New York, N.Y. (Decca), as well as an interesting but disjointed Cecil Taylor album released at first as Hard Driving Jazz and later as Coltrane Time (United Artists).

A final thought: Sonny Rollins is deservedly hailed for his track record as one of jazz’s great song sleuths, introducing numerous tunes that no one else knew or recorded. While Coltrane’s 1960s repertoire didn’t include many obscurities, Coltrane ’58 is chockablock with forgotten material, such as Buddy DeSylva and Vincent Youmans’s “Rise and Shine,” Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz’s “If There Is Someone Lovelier Than You,” Mack Gordon and Harry Revel’s “Love Thy Neighbor,” and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Do I Love You Because You Are Beautiful?” (which was introduced in the televised musical Cinderella the year before). A seeker in all things, Coltrane was always on the lookout for a lovely melody. It’s yet another reason why he remains as powerful a force as ever.