If there is one lesson in physics the pandemic has taught us, it’s that time is elastic. Weeks can feel like months; one year felt like ten. But with the introduction of mass vaccinations, we have begun to resume our pre-2020 lives.

Over the past month, the San Francisco Symphony returned to Davies Hall for live performances; the New York Philharmonic conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen concertized in a vast space called The Shed; and Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed for a live audience of 4,000 essential workers and first responders at the Hollywood Bowl after an 18-month hiatus.

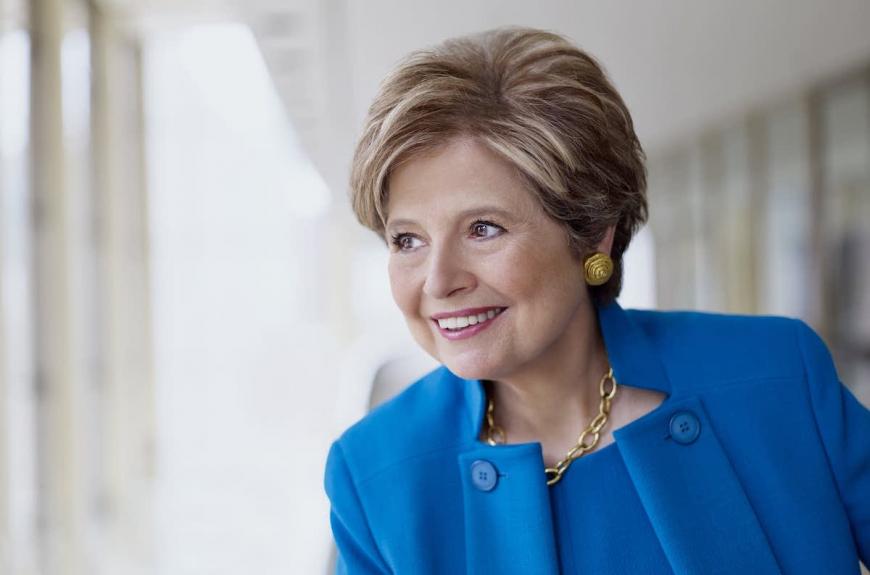

“I’m definitely optimistic,” observes New York Philharmonic CEO Deborah Borda. “We can see the light at the end of tunnel. The question at this point is, how long will the ride through the tunnel be?”

It’s an astute observation because as institutions like the NY Phil begin to gear up many critical issues remain fluid including the economic realities of returning to halls with reduced seating capacity and the necessity of having all musicians onstage, as well as audience members, vaccinated. And there are psychological factors: primarily, will audiences feel safe and secure returning to concerts?

Borda got a crash course in the new incarnation of live performances when the NY Phil performed its pair of concerts at The Shed in mid-April.

“When you talk about the ability to act fluidly,” she says, “those concerts were a perfect example. They were organized and presented in two weeks. It was sheer luck that Esa-Pekka [a long-time friend and collaborator of Borda’s] happened to be in New York on his way to Finland.”

The process, Borda explains, was challenging.

“There were two ways we had to prepare. One was very technical — putting all the safety and health provisions in place. Then there was a very strong emotional component that also had to be put in place, both in terms of the musicians and the audience, because everybody had to feel safe. It was very complicated. There were so many layers.”

The Shed is a presenting organization located in New York’s Hudson Yards. Its McCourt performing space is basically a cavernous box.

“It’s quite a big space that can hold up to 2,000 people. We were allowed to have 125. The musicians (all string players) had to be masked and distanced by six feet. Because of the need for air exchange, the air conditioning system had to be running throughout the concert and you could hear it quite distinctly. And we had to amplify the orchestra. It was very challenging.”

After the announcement of the two concerts in April the audience faced a sequence of hurdles and requirements, Borda explains.

“Tickets were issued online. You had to be able to show your COVID vaccination certificate and that it was at least 14 days out, or you had to have been tested ahead of time. That was just to get an online ticket. The ticket told you when you were allowed to arrive. Then, when you got in the theater you had to have your temperature taken. Next you were guided to your seats which were set apart in pods of two. At the end of the concert, you left by rows. It reminded me of being back in sixth grade assembly,” she adds with a laugh.

What fascinated and surprised Borda most, was the entirely different ways the musicians and the two audiences reacted.

“The members of the New York Philharmonic don’t get nervous. They’re total professionals. Let’s just say there was definitely a heightened level of emotion backstage the first night. You could also tell the audience was edgy, or I’d say, apprehensive. I thought there would be an emotional explosion. They obviously liked it. But the reaction was very subdued. The second night when people came — I don’t know if they’d read about it or what — but they were much more relaxed and jubilant. At the end, they went crazy, which is what I expected to happen the first night. Those concerts [the first live performance for the orchestra in 400 days] really offered a glimmer of hope.”

The Yin and Yang of the Pandemic

When the San Francisco Symphony made its long-awaited return to Davies Hall on May 6 (ironically also conducted by Salonen, SF’s new music director), CEO Mark Hanson, described to me the way that moment felt.

“It was a beautiful shock to the system, because it had been so long since we had been able to enjoy a live music performance with an audience. In some ways it felt so normal — a transition from a concert-less world back to the world we’ve missed. In some ways it felt like it was just yesterday since our last performance. But, at the same time, it felt like it had been years since we’d been able to share a collective concert experience.”

Strangely, Hanson sees the period of rapid change we are in now as being equivalent to the rush to adapt that arts institutions experienced at the onset of the pandemic.

“Oddly, right now feels just like it did during the first months of the pandemic, when the news was changing on an hourly, certainly on a daily basis, and we were constantly having to adapt our plans. Fortunately, now, unlike then when the news was always getting progressively worse, now the news is getting better and better with each passing hour. Ironically, the same principles apply now as during the first months of the pandemic — we have to try to constantly make the best decisions we can based on the information that’s at our disposal. And that information can, at times, be contradictory.”

Borda and Hanson both acknowledge there are still a lot of questions, protocols, and psychological hurdles that need to be addressed: do the CDC’s recommendations or the state’s guidelines concerning masking and gathering apply? How can people be required to show proof of vaccination at a time when health protocols and some people’s personal politics are at odds? When will indoor concert venues and opera houses be able to operate at full capacity and with what safety guidelines? How does of reduced audience size and ticket revenue affect the organization’s overall economic outlook?

When the San Francisco Symphony offered its first live concerts, only 400 audience members were allowed in a hall whose capacity is more than five times that. Likewise, when the LA Philharmonic returned to the Hollywood Bowl (which seats over 17,000) only 4,000 tickets were made available.

Soon, though, Hanson expects the attendance numbers in San Francisco to rise to 1,400 for the upcoming concerts in late May and June. Plans are also in the works to present a series of outdoor concerts in the Bay Area throughout July and August.

“One of the problems,” Hanson observes, “is at this point there is no nationwide system for vaccine verification. We are requiring a combination of the CDC card with a photo ID that confirms the identity of the ticket buyer. But we also have to rely on a degree of trust that people will do the right thing.”

“Anyone with an outdoor venue at this point is in great shape,” Borda observes as her orchestra makes plans for its annual summer visit to Vail, Colorado. And following a series of free limited audience concerts, the LA Phil is looking forward to an almost full summer season of concerts at the Hollywood Bowl beginning with a blowout concert on the Fourth of July.

The return of anything resembling full summer seasons raises questions regarding the safety of musicians. After so long a lay off from regularly performing, musicians, like athletes, may need time to build up their conditioning. A too rapid return to demanding schedules, such as the Hollywood Bowl, could quite possibly result in injuries.

There is also the question of the substantial union-negotiated pay cuts that musicians accepted. Any return to prepandemic salaries may be predicated on venues being able to operate at full capacity. If protocols continue to limit the size of the audiences, musicians may find themselves contractually obligated to play full concert schedules for considerably less pay.

The Indoor Venues

While orchestra and opera companies had rosters of singers and musicians they could tap into for online content, major presenting organizations like Cal Performances, CAP-UCLA, and the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts (in Beverly Hills) faced disaster as entire seasons disappeared.

“The Wallis is actually a presenter and a producer,” explains Artistic Director Paul Crewes. “At the point when the shutdown came, we were in the middle of producing a piece for dance called The Minghella Project written by the late Anthony Minghella. The whole presenting side of the business came to a complete standstill within four days. We went from a place that produced and presented shows, to a place cancelling and postponing shows. For presenters, the timeframe for locking in calendars is in terms of years. When our season collapsed, we were left with nothing.”

Like so many other organizations, The Wallis eventually moved content to the internet. But now with restrictions loosening, Crewes says The Wallis is in the process of building its own outdoor stage, 36 feet wide and 24 feet deep with raised seating for an audience of 100 (socially distanced) and 240 at full capacity.

“Our intention is to present a mini-season on the outdoor stage leading to indoor presentation on our two main stages in the fall. Of course, attendance restrictions will have a lot of impact on what we are able to present. We certainly can’t afford to put on a fully staged musical for 50 people.”

The Wallis plans to inaugurate its new Promenade Terrace Theater on June 23 with the world premiere of Tevye in New York, a one-man show based on the characters of Sholem Aleichem, written and performed by Tom Dugan.

“I actually love the fact that we are reacting and having to act differently. The old formulas don’t work at the moment. And when it comes to ticket sales, people are not going to put their money down when there’s still so much uncertainty.

The Takeaway

One of the echoing questions that Deborah Borda and Mark Hanson are facing will be how much of the creative ingenuity that’s gone into surviving the pandemic will carry over once we return to “normal.”

As Borda sees it, “I think every orchestra is trying to figure that out and find the best path forward. Everybody is thinking about how have we changed, what we have learned, and how we can build on that?

Hanson sees live streaming of events and performance captures as definite positive outgrowth of the pandemic experience.

“There is no question that the last year has been very difficult and painful for our industry. So many people have had to make sacrifices. At the same time, there are silver linings that have emerged. One of those is that we have been forced to be more nimble and more expansive about how to disseminate our performances and showcase the talents of our musicians and collaborators through digital means. We are committed to maintaining our digital presence for many years to come.”

And while it was not a direct result of the pandemic, this last year has caused all arts organizations to look deeply into their commitment to promoting racial diversity.

“The San Francisco Symphony’s commitment to more racial inclusivity predates the pandemic. But now we feel an even greater sense of urgency and opportunity because of what our world has experienced over the past year. That is definitely a silver lining that has emerged.