Violinist Alexi Kenney loves the music of J.S. Bach, especially the notoriously difficult Chaconne from the composer’s D-Minor Partita. But Kenney’s musical interests hardly stop there. He has forged a career that defies categorization, creating experimental programs and commissioning new works while soloing with major orchestras and collaborating with some of the world’s most celebrated musicians.

Kenney’s talents will be on full display when he makes his debut at the Ojai Music Festival, which runs June 6–9. The violinist will appear in four performances, including his highly touted project “Shifting Ground,” which intersperses seminal works for solo violin by Bach with pieces by, among others, Matthew Burtner, Mario Davidovsky, and Paul Wiancko. Then, on the festival’s final day, Kenney and soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon will perform György Kurtág’s fiendishly difficult Kafka Fragments.

Born in Palo Alto in 1994, Kenney began studying violin as a child, going on to graduate from the New England Conservatory in Boston. In 2016, the musician was the recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant, and in 2020, he earned a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award. He’s been on a musical tear ever since.

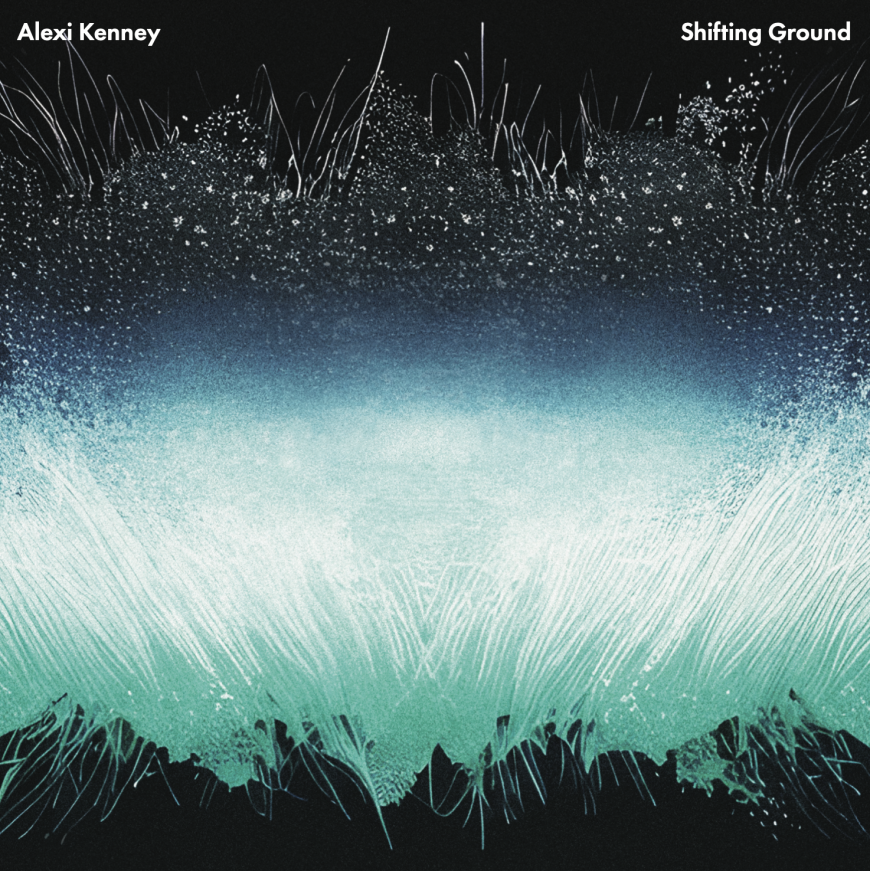

Indeed, highlights of Kenney’s 2024 so far have included soloing with the Dallas, Pittsburgh, and Milwaukee Symphonies and leading a program of his own creation with San Francisco’s New Century Chamber Orchestra. In April, he premiered his latest iteration of “Shifting Ground” at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, working with video artist Xuan. An album of the program is set to drop on June 7 and will include Kenney’s own arrangements of pop star Ariana Grande’s “Thank U, Next” and Joni Mitchell’s “Blue.”

SF Classical Voice caught up with the New York-based musician from Charleston, South Carolina, where he was performing at Spoleto Festival USA. Topics of our conservation included his Ojai debut, his love of contemporary music, and “Shifting Ground.”

Was there music in your family, and why the violin?

No one in my family is a professional musician, but my dad had a huge record and CD collection. There was always music playing in the house — [John] Coltrane, Bill Evans, Brahms, a lot of world music, and everything in between. But it was my mom who noticed [that], even in the crib, I would perk up when strings or violin music were being played.

She was searching for an instrument — once I could hold something — and thought, “He seems musically inclined.” My mom was driving or walking by a church at the end of our block and [saw] kids with violin cases walking in. She went in, and there was my future teacher, Natasha Fong, [who] said she didn’t take 4-year olds, but my mom begged her to take me. [They were] nurturers rather than pushers, and I feel very grateful. That belief they held — that music should always be coming from a source of joy, not pressure — is something I very much believe in.

Let’s talk about your Ojai programs, beginning with “Shifting Ground.” What was the genesis of this project that juxtaposes works by Bach and Nicola Matteis with music by contemporary composers? And what does the title mean?

I’ve always loved Bach and connected to [his music] very deeply. My second teacher was Jenny Rudin, and her favorite piece was the Chaconne. She taught it to me when I was 10, [but] I couldn’t get through it at 10, and it’s still hard to get through at 30! It’s the kind of thing that is so universal [and] encompasses a lot of what we feel as humans. It’s always been a fascinating and beautiful and cathartic piece to play.

But to play it on its own, [or] if it was stuck in the middle of a recital — it’s hard for me to get in the zone for that. [The Chaconne] is so intense, dark, and immediately emotional, it’s kind of jarring if it comes by itself. I thought, “How can I introduce the piece or elide it with something that would get myself and the audience ready to receive it?” I was building off that idea. I would play a three-minute introductory piece and then go into the Chaconne. It’s developed into an epic 60-minute continuous set that all concludes with the Chaconne.

[As for] the title, “Shifting Ground,” there are a few things behind the name. One is [that] it’s not your typical solo Bach recital, but the kernel of it was Bach. I’m trying to bridge a lot of different eras and, at times, different genres. There are a lot of new pieces on this program that are maybe subconsciously inspired by Bach, by virtue of all these composers being steeped in that language, but there’s so much diverse writing on the program.

I’m proud of how it’s come together. It feels like you’re hearing the total gamut of what’s possible on solo violin — and then some. We’ve added electronics and tapes. The way composers use those devices are all vastly different from each other. That’s in the title — shifting away from something that’s expected. [The title is] also an allusion to the ground bass, the Baroque form, which is what the Chaconne is built on top of — repeating the bass line. It comes over and over and over again.

What about the composers you commissioned — what are their works like?

I gave [the composers] an overview of what the project was, but I wanted to let their minds go wild. I’m only playing a movement of Paul [Wiancko’s] piece, which is a larger suite in seven movements and was inspired by Baroque forms. Salina Fisher’s commission was for solo violin with arpeggiations, and the harmonic language alludes to Bach.

Angélica [Negrón] has constructed a dubsteppy, electronica soundscape that I accompany. It’s a very cool, unique piece [and] provides some relief from the intensity [because] it’s a non sequitur, a narrated short story that comedian Ana Fabrega is reading on tape. It’s about her having a nightmare [about] being asked to play the violin in public and she doesn’t know how. It’s a meta piece — over the top — around that narration.

You’ve also added Xuan’s visuals to this version, so what can audiences expect to see?

I had done a program in altered form, with a lighting designer, last spring in Princeton, but there were no projections. After that, I started thinking what the next step might be. Pedja Muzijevic, the artistic administrator at Baryshnikov Arts, had the idea to pair me with Xuan, who is also a pianist. I’d heard about her years ago from Paul Wiancko and had been wanting to work with her, [so] we met over Zoom and discussed the emotional trajectory, potential themes, the colors of the [program].

I think of music [like a visual artist would] — in texture, density, color, and weight. All these things visually make sense to me, [so] we found common language quickly and easily, which was cool. Then we let each other be for a few months [before] meeting at the Baryshnikov Arts Center. She came up with projections that week. We had three days to build the show, [but] we felt a bond when we met in person.

After seeing her visuals, it floored me how true to my vision of the program her visuals were, yet there’s so much I think they add to it as well. The video is close-ups of broken glass, ice, water, and these sorts of things. Her theme for the program is fragmentation, mending. It’s very apt [as] I think a lot of the pieces deal with grief, loss, and getting over that. It’s a beautiful collaboration.

On June 9, you’ll not only be performing Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber’s Passacaglia for solo violin in the morning as part of a larger bill. You’ll also later that day be tackling Kurtág’s Kafka Fragments with soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon.

[Kurtág’s piece is] the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to play; I say “tried to play” because it’s so difficult. But I’m very happy to be doing it. I’ve never played it [before], but [Ojai] Artistic and Executive Director Ara Guzelimian wanted this piece to be played. [Ojai Music Director] Mitsuko Uchida is friends with Kurtág and plays a lot of his music as well. It’s pretty monumental. It’s 70 minutes long, with 40 movements in four parts — a complete tour de force.

The way he uses both violin and voice I would say is unique, unparalleled. There is a lot of crazy virtuosic writing, and before I practiced [the piece], I didn’t know [certain things were] possible on the violin. It’s kind of mind-blowing how deep and complex it is, and it’s great to be doing it with Lucy. She’s [done] it quite a lot and knows it inside and out.

You’ve also got a group, Owls — violist Ayane Kozasa, cellist Gabriel Cabezas, cellist and composer Paul Wiancko, and you. Is it still happening?

Yes, but we’re all super busy. Owls is four good friends who come together and play stuff that makes us happy. We come up with our own arrangements and don’t play anything that’s been written before. It came about because we were looking for a creative project — and to play with friends. I don’t want to say it’s a nonprofessional setting, but we don’t need this group to make a living. We have the main stuff that we do.

The plan is we’ll start commissioning stuff when we have more concerts to play. We have one gig this summer and a few things next year. We also have an album in the works — one great set [of pieces] that we love. [Note to San Francisco Bay Area readers: Owls is set to appear at Cal Performances at UC Berkeley on April 13, 2025.]

What do you think of the state of contemporary music today?

I think people are a lot more aware of music as a spoken-of art rather than [in] its own little corner, which can sometimes happen in classical music. For me, the more people investigate what music means in the larger context of the world and how they can bring their unique, individual selves to that conversation can only be a good thing.

I wouldn’t want to veer away entirely from the classics, but new music is so important — and I hesitate to use the words “new music” because there’s so much variety. I think we’re living in a great age for music. So many composers are doing what they believe in, regardless of what the past was, and I think it’s really cool to look around and be a part of that.