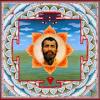

Like Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan a couple of generations before him, 47-year-old tabla drum maestro Sandeep Das has made a musical and spiritual mission out of transporting the classical music of his native India to the West and around the world.

Apprenticed to a guru as a child, Das performed with Shankar at 16, made his American debut three years later, and graduated from Banaras Hindu University with awards in English literature. He was recruited by cellist Yo-Yo Ma for the formation of the Silk Road Ensemble in 2000, with which he won a Grammy and was nominated for another. Das performed separately with the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, as well as the group Ghazal, with which he was nominated for another Grammy with Iranian-Kurdish kamancheh player Kayhan Kalhor and Indian sitarist Shujaat Husain Khan. He has also composed for orchestral and chamber ensembles as well as for his own, even though he neither reads nor writes music in standard Western notation.

Das has taught and served as artist-in-residence at several American and Canadian universities, and he hosts a tabla camp in Vermont. He’ll appear at UC Berkeley’s Hertz Hall with his HUM Ensemble, whose Delhi to Damascus project explores boundary-crossing musical and cultural connections vital to contemporary war-torn regions. Das’s glee in his raising and music-making was manifest throughout an hour-long conversation with SFCV from his family home in Boston.

What was your first home?

I was born and raised in a city called Patna, in eastern India, but then I studied with a tabla maestro named Pandit Kishan Maharaj, and lived in his house in Varanasi.

He was your guru. How did you connect with him?

It all started with a complaint from school, when I was six, that I had been disturbing the class by tapping on the desk, and tapping with my feet, so I should be taken to a doctor. But my father was a wise man: instead of taking me to a doctor, he got me my first pair of tablas. My father had been a fan of Kishan Maharaj since his school days, so he worked hard to get in touch with him, and took me to him when I was seven. He tested me with certain things, and after an hour told my father that I had tabla in my blood, and that he would teach me.

I studied by living with my guruji for 12 years. Tabla was not taught to me as an instrument. It was taught to me as a way of life. So a lot of my lessons were riding horses, enjoying the swing in the garden, weeding the grass, stuff that at that time didn’t make any sense to me, but has later, with every passing day. My guru was very strict, but at the same time he opened our eyes and ears to everything. To me, 7/4 is not a rhythm, it’s just a horse running free. And I remember so fondly him saying this: your initial practice is to turn your hands into swords. With more practice, they will turn into strings, and music just flows out of them. And then, if you are blessed and lucky, they will turn into flowers.

I wish all my teachers had been so poetic.

I could go on and on talking about my guru! [laughs] If he’d been born in the West, with the way people revere Bach and Beethoven, he was one of them. Another example: he would say, “Don’t try to master something.” As a young kid, I was very confused: “You are at my throat if I am not practicing eight or 10 hours a day, and then suddenly you say, don’t master it!” He would say, “If you try to master it, it will leave you when you need it. Try to get to know it. When I give you a new composition, say hello to it on the first day. Next day, if you are lucky, it will tell you who it is. Then, ask for the address. Then, in six months, if you become friends with this composition, it will always be there when you need it, say, if you are playing at Carnegie.

It sounds like getting to know a woman.

Yah, that’s a nice analogy! [laughs] Because, one time he got very angry at me, I was 15 or 16. I was practicing and he started playing along with me and then said, “Do you have a girlfriend?” I didn’t know what would get me killed, yes or no, so I said “No,” and he said, “That’s why! There is no love in your playing! Put your tablas on the shelves, go find someone, then come back and play.” Now, I look back with gratitude. I loved both my father and my guru, but I tell to my wife and my daughters that I miss my guru more than my father.

Did your guruji associate himself with a particular gharana [musical tradition passed down through family and/or apprenticeship]?

Yes, he represented the Benares gharana. I remember once playing a composition from the Delhi gharana, and he walked in and heard me, and I just froze. He said, “What happened?” I said, “I’m sorry.” He said, “I didn’t scold you, what are you sorry about?” “I’m sorry I was playing a composition from the Delhi gharana.” He said, “The only mistake is, you’re playing it like them, and as long as you play it like them, they will always be better than you.” Then once, I played a concert, and at the end of the concert I went to take his permission before going to sleep. He clapped and said, “So, that was a great concert, you sounded just like me,” and in his expression there was something telling me that I shouldn’t celebrate. He was looking at a trash bin in the corner of the room. He said, “My son, with your first note, people should know whose student you are, whose gharana you belong to. But if you’re merely a copy, that is where you will end.”

What did he think about music from the West?

He always said, don’t judge anything based on what you know and don’t know. Something which is good is good, irrespective of which culture, which religion, which philosophy it comes from. And he would invite folk musicians he’d just heard at a railway station to come play at his home, a place where Ravi Shankar or Ali Akbar Khan might come to play.

I remember Yo-Yo Ma pointing out that Ravel was very influenced by music from the East, and had met a sitar player at the opening of the Eiffel Tower. Yo-Yo himself, when I first met him, I didn’t know who he was. I was rehearsing with the New York Philharmonic, and I went up to the principal violist and said, “Who is that man on the big violin? He’s so good! Is he well known?” She said, “You mean, the cello? That’s Yo-Yo Ma!” She thought I was joking. But what I knew was, that when he played, he touched my soul. I would say that my second guru is Yo-Yo Ma, because he’s the biggest, nicest human being I’ve met, and I’ve learned so much from him. I think I’m the only tabla player with string quartets and orchestras on a regular basis. It keeps me up, the fear of failing with an orchestra when everyone else is reading a piece that you can’t read. I like challenging myself.

How do you share your own compositions?

Yo-Yo called me when I was touring with Ravi Shankar in Malaysia, and said, “I want you to write a piece for us, for the Smithsonian Festival.” “I would love to, but you know I can’t write music down.” He said, “How would you do it if it was Indian music?” I said, “We share ideas, we share notes.” So all my initial compositions, I would sing the tunes, my friends would beg to write them down, but I wouldn’t let them, I forced them to memorize the music. For my King Ashoka, I took a bass player friend of mine out of San Francisco, Matt Small, and literally sang the notes, and he wrote them down, and it’s a very successful piece. I took some lessons in reading from a manager of Yo-Yo’s, and started getting good at it, but to be honest, when I got home, there was no music that excited me to read, so I lost interest.

How did you conceive of your new ensemble, which we’ll be hearing in Berkeley, and is its name spelled in all caps?

I started with “hum,” which means “we” in Hindi and also the sound of humming, and I was inspired by the Silk Road Ensemble, thinking about reconnecting with old cultures in a modern context. But then I started an organization in India, HUM, which I’m very proud of. It supports seven visually-impaired students, to learn music: we pay for their transportation, their guru fees, everything.

And the Delhi to Damascus theme?

It questions the role of music, culture, and art in our lives and in our current scenario, how we must popularize these things to foster connections among individuals and communities, to shape a world perspective through musical compositions. The next series could be Delhi to Shiraz, and Delhi to Beijing. I don’t make any political statements, I just have fantastic players. Issam Rafea, our oud player, is from Syria, and he’s now out of Chicago, where he teaches. My sarangi player, Suhail Yusuf Khan, comes from a well-known lineage from Delhi, was studying ethnomusicology, and suddenly decided to move to Wesleyan, in Connecticut. Rajib Karmakar is a brilliant sitar player who learned in the same city as me, Varanasi. He’s studied sound engineering at CalArts.

The path from Syria to India parallels the influence of Persian on Indian music. The common roots go back a long ways.

People date it from the time of the Mughals [16th century], but I somehow feel it predates that, because every Hindu god or goddess will always have a musical instrument in her hand: Shiva played the drum, Saraswati played the veena. I somehow feel it’s shared culture and music, and now that I feel that way, I feel more protective towards it. It’s no longer just an Indian musician playing Indian music and representing Indian culture, I think I am a world musician representing world culture.

That’s something very funny, because the West is so used to getting a list of repertoire that when I say, “to be announced from the stage,” they get very confused. [chuckles] I will share with you that there are compositions based on traditional Indian ragas, some inspired by folk tunes from Rajasthan, which I feel are important because they influenced the Middle East and the Roma, the gypsy musicians. There’s a kind of singing called thumri, which is a colorful form I grew up listening to, semi-classical. There’s a piece influenced by Syrian folk. And there’s some new repertoire that we have each composed.

As a tabla luminary, do you find yourself compared with Zakir Hussain?

Any time I see musicians like him, I see the hours of sacrifice, the hours of practice, the hours of research, and I see the tons of blessings you need to even get close to who they are. If he’s around, I would love to go and get his blessings. I won’t want my epitaph to read, “Here lies the world’s greatest tabla player.” I want it to read, “Here lies the happiest man on the planet.”