When pianist Awadagin Pratt won the Naumburg International Piano Competition in 1992 at age 26, he wore a dark tux and tails. In the years since, he’s ditched the penguin suit and begun showing up onstage in T-shirts (sometimes colorful shirts by Versace). His concert look — casual performance apparel, plus full beard and long dreadlocks threaded with gray — has been described as idiosyncratic. His style goal, however, is less about making a fashion statement and more about breaking down perceptions of classical music as stuffy and bringing more people into that world, he’s said.

Bay Area audiences will get a chance to see for themselves when the virtuoso pianist joins Daniel Hope and New Century Chamber Orchestra for a program of contemporary American works for strings May 2–4, with performances in Berkeley, Rohnert Park, and San Francisco.

A program highlight will be Pratt and the orchestra playing Jessie Montgomery’s vibrant work Rounds, which won the 2024 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Rounds is nearly a piano concerto — Pratt’s fingers leap off the keyboard and fly back again in a harmonic swirl infused with radiant energy and packing heat. Montgomery and Pratt had previously collaborated together as chamber musicians, and she wrote Rounds especially for him.

Pratt, 58, known for his intense engagement with audiences and his gifted musical sensibilities, joined the San Francisco Conservatory of Music as professor of piano in July 2023, coming from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

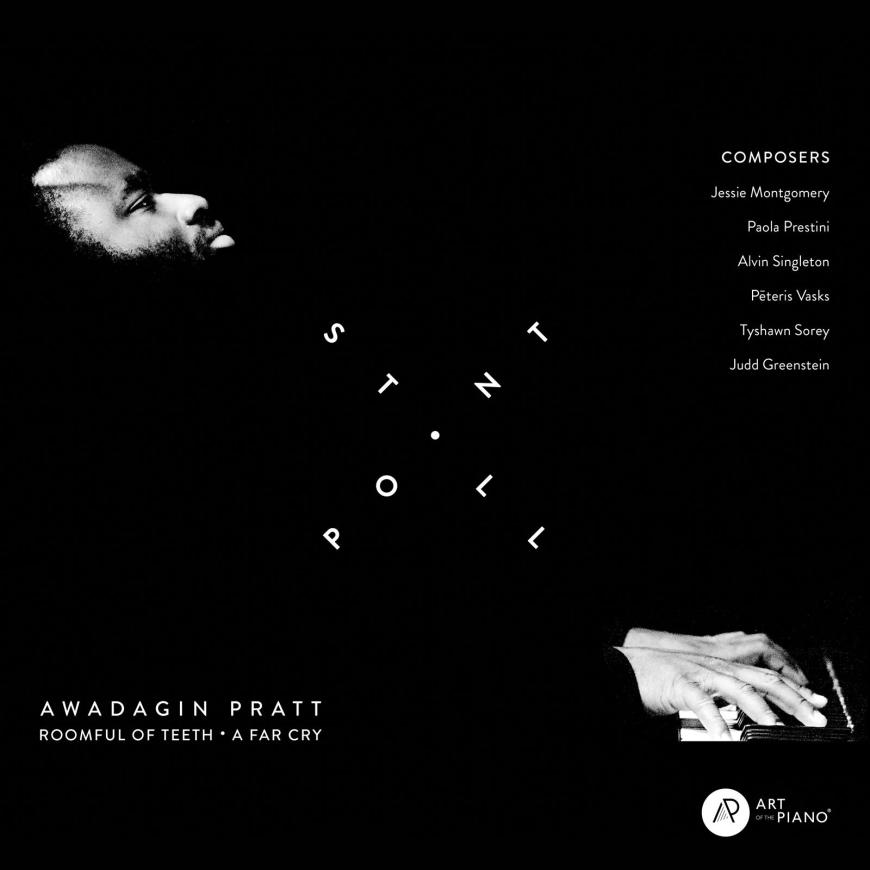

His latest album, Stillpoint, released in August 2023, contains seven works for piano, strings (A Far Cry), and vocals (Roomful of Teeth) by Montgomery, Tyshawn Sorey, Judd Greenstein, Jonathan Bailey Holland, Paola Prestini, Pēteris Vasks, and Alvin Singleton. Pratt’s Art of the Piano foundation commissioned each composer to create a piece using “Burnt Norton,” the first poem from the T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, as inspiration.

SF Classical Voice spoke with Pratt via Zoom from Cincinnati, his home base outside of San Francisco.

Why do you no longer wear a tuxedo when performing as a classical pianist?

For me it was a question of comfort and accessibility. It’s a very formal construct to wear one. There were a bunch of customs I think that originated in classical music to keep people out of it. It was for the haves and not for the have-nots.

People wearing tuxes are the rarity right now as far as concert pianists, violinists, and conductors. I'm happy that I was on the forefront of that. I think it’s all for the better.

Tell me about what you wear to perform in and why?

I separate the clothing that I wear for performances [from everyday clothes]. I’ve just started this year performing in black jeans, and I don’t think anybody’s really noticed. But even the jeans I have are a set of concert jeans.

I just did a triple in Annapolis this weekend. So [for a set of three performances], there are three different shirts that I travel with for each concert, and the only thing that happens is kind of choosing which of those three I would be wearing on a given day. I wear either black or dark blue shoes, and then, depending on the shirt, I have socks that match.

Were you surprised that Rounds won a Grammy this year?

Yes and no. We were hopeful. It’s a terrific piece of music. People love it, and the recording is great. But there were other noteworthy candidates. You just never know how many of these things are going to go.

What was it about Montgomery’s music that led you to commission Rounds from her for your album Stillpoint?

At the time of the commission, I had not heard a lot [of her music]. We’d worked together before and spent a week at the Cortona [Sessions for New Music]. She was still then primarily a performer but was contemplating becoming more of a composer.

I liked her intellectual range: the way she thought about music, the way she thought about society and the world that we live in.

I didn’t know all of the composers [on the album]. But from that week at Cortona, when she was talking about potentially shifting to being a full-time composer, I thought, “If I have the chance to commission her, I will.” The chance came up five or six years later, so I did.

When did you first hear what Montgomery had written for you?

I didn’t see anything until she had sent me the score. I played through it, and then we talked about a few things in terms of what kinds of sounds she wanted in a certain place. There were no material changes at all. Just maybe certain registers were changed. There was a place for a cadenza, but there was nothing there. Time was narrowing, and I was concerned about being able to learn it before the first performance. I already had a practice in my recital programs of improvisation. So I started playing around with some ideas and sent her a recording of a minute. She was like, “Why don’t you just take control of the cadenza?” And so the cadenza is mine, and I improvise between 10 and 20 percent of it. It’s different every night.

Had you any idea of her gifts as a composer?

I was not surprised by the quality. Two things I can tell you: One is that when you look at a score, you learn a piece — and I don’t play at home with an orchestra. And so, there are places where, on the page, I imagined certain things would be really kind of beautiful and powerful and affecting. And it was great to hear those things. The quality remains every time.

The other thing is that in the same way I see and explore new ideas and find new relationships in a Beethoven concerto, I find that same level of craft in her piece and her work. Even with these 30-some performances, I keep mining the material for different ways in which to engage with the piece.

What has been challenging about performing Rounds with various orchestras?

Initially, you’re just figuring out how the piece goes, how the energy flows. The beginning is a lot of newness. What’s really good is that each conductor brings something to the table. There are some new ideas or ways in which they conceive of the sound of the orchestra. I wouldn’t say it’s challenging, but it keeps it fresh.

What keeps you transforming as an artist?

I think it’s being curious, exploring and asking why enough times, purposefully. Hearing new repertoire, whether it’s newly composed or older pieces that I didn’t know, is always inspiring. I like rediscovering pieces I’ve known for a long time. I don’t have a prescription for how I keep evolving.

What’s the biggest takeaway you hope New Century audiences will have from hearing how Montgomery was inspired by Eliot’s poem “Burnt Norton”? Or maybe you don’t think about that?

You know, actually you’re right. I don’t [think about it] because two people sitting next to each other will hear it differently. Every time somebody encounters a piece of music, it’s an individual experience, and I don’t want to prejudice someone about how they should feel or experience it. If they didn’t have that feeling that I suggested that they should, they think, “Oh, maybe I didn’t get it.” No, you got it exactly how it came to you is what it is. I just hope they enjoy it, or are moved by it, and receive it openly.