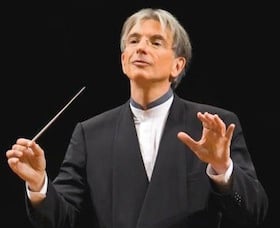

This centennial season of the San Francisco Symphony promises to be spectacular, packed with programs and guest artists, including well-known names, new works, and guest symphonies. The American Mavericks Festival returns, as well, and offstage exhibits and multimedia projects will be offered. The face of it all, as he has been since 1995, is Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas. Here he talks about conducting, orchestra personalities, the Symphony’s varied programs, and how a dog is necessary to keep you grounded.

Jumping right in with questions about conducting, when you interviewed James Brown, who I know you’re a big fan of, you talked about determining when the “now” is when conducting or playing in an ensemble. Can you elaborate, or is it something you need to hear by listening to Cold Sweat?

It’s “where” the “now” is. When people are getting together to play, everyone comes with their own hardwiring about the basic concept of the center of the beat. When it’s three or four people, you can look at each other. The larger group with more people is harder. Also, some instruments also have slow reaction times, like the strings, where the bow starts the note, or the low horn. The harp is instant. So is the drum.

How do you help the orchestra achieve that?

I pay attention to the people on the periphery rather than the people next to me. I pay attention to those on the edges: How comfortable are they? Do they need information from me to give them confirmation? If it’s been well-rehearsed, the confirmation should happen.

You’ve now been doing this from the time you could be considered a prodigy.

“Late prodigy.” The last days of prodigy!

You learn from your mentors. You also learn from watching other people work.

You’ve said conducting was accidental. How did it happen for you?

I was around 13 or so. I was in a beginning orchestra in junior high school, back when the California schools had beginning orchestras, intermediate orchestras, and more. The instructor didn’t show up and they sent in the football coach. He said he didn’t know what to do, so we could either have study hall or see if someone felt like they could do this. I raised my hand.

It’s worked out well.

It kept me out of football.

What did your mentors and your own experience teach you about how to connect with orchestra musicians and lead them?

You learn from your mentors. You also learn from watching other people work — things to do and things not to do. But there are things that you do that are natural for you. I always feel like it’s a relationship I’m forging anew every time I step in front of musicians. Even for as long as I’ve been here.

Speaking of the San Francisco Symphony, reviews of your recent European tour described the “American brass sound.” Do you think orchestras have recognizable musical personalities?

They do. I think the San Francisco Symphony has several personalities, maybe because it’s San Francisco. When we play French, German, or Russian repertoire, we have a different sound.

Maybe because of my background, I have a view of an orchestra as a repertory company that puts on a play by Euripides, then by Beckett, Steve Sondheim, Shakespeare, and they’re all excellent and stylistically different.

In general, I like to encourage the soloistic, colorful, gestural, quite “dangerous” or “risky.” We’re comfortable going to a lot of spaces that other orchestras are too paralyzed or vulnerable to consider.

Now that the Mahler recording cycle has been completed, are there still mountains left to climb?

Certainly.

What are some of them?

We’ve already done the extraordinary Ives/Brant symphony, Beethoven’s Fifth and his Fourth piano concerto with Emanuel Ax.

My greatest contribution to many situations is that I have a lot of context. I know the history of music and what I’ve seen happen.

What do you do when you want to get back in touch with your own creativity?

I go to little towns in the country and get away. I like to see a lot of landscapes. Big skies, big hills. I’ve gone to the Southwest a lot, and I’ve been going north of the city. You have to like fog. I like fog.

The S.F. Symphony seems to be surviving the recent turmoil in the orchestral world pretty well. Can you talk more about the organization as a whole?

It’s a wonderful organization. The musicians have such varied interests, and have “real lives” away from their musical lives that makes it exciting. A lot of them do quite physical, outdoor things.

The staff is remarkable, from John Goldman, who is the chairman of the board, on. After so many years, there is a devoted sense of caring about the orchestra, cherishing what it is and what it will be. That’s not necessarily the case in other orchestras. You’ve read the stories and can read between the lines. There’s no harmony.

The Symphony has done very well at education and outreach, especially Keeping Score [the orchestra’s PBS series and national educational program] and the Bass Training Program. What feedback have you gotten on how Keeping Score is working out for educators and others?

The distribution is greater. It’s being sliced and diced, and that’s terrific. But it’s still a question of context. At this point in my life, I think my greatest contribution to many situations is that I have a lot of context. I know the history of music and what I’ve seen happen. That can be valuable, and you want to share it, especially when working with young musicians.

But we don’t know, with all the sorting and slicing and dicing, how much sticks. Someone from my generation was interested in how much you retain. But I think there are confluences that happen inside your brain. When I’m studying pieces that I’m coming back to, months and months before we’ll be doing it, I will open the score and look at the pages with no conscious thoughts. Then sometime later, when I’m doing something else, part of the music will come to my mind and I hear how it should be. Often, it’s something I wasn’t satisfied with before.

I think we have files of these things inside us, and they’re telling your mind to open and start working.

I know what you mean. I’ve found that I can find solutions when I go out and do something totally different and not think about the problem.

That’s why dogs are so important. They distract you from problems by telling you it’s time to pay attention to them. My dog would come over and distract me.

Do you still have Sheyna [his standard poodle]?

No, unfortunately. She lived to 15½, in good health, but then the last two weeks of her life she was saying it was time.

What more is the orchestra doing to reach out to the community and maybe attract more people to classical music?

The process of engaging new audiences is always vital and will never go away. We’ve got a new program for adult education. But most programs focus on the kids. If they can hear music in a delightful way while they’re developing language skills, they will keep the interest. They’re often more capable of hearing and understanding complex music than their parents.

There is a connection between everything — music, art, dance, cooking, pottery, gardening.

With fewer school programs, it’s become the responsibility of the arts community to step in. Nationwide and worldwide, there are a lot of people doing quite a lot. We don’t realize it. I’m always surprised when I go places and find out about programs. In Luxembourg, there’s an astounding program for three- to five-year-olds and their parents, and they’re listening to quite sophisticated music. We need to be more aware of this.

You also have your own YouTube channel.

The problem with that is the difference between real life and online life. I’m so busy dealing with real life that I can’t keep up with online life. I’m going to carry a flip camera.

Organizations like yours [San Francisco Classical Voice] are doing a lot to champion the music. At the New World Symphony [his second orchestra, in Florida], we’re also developing the Internet tools. We were doing rehearsals of Beethoven with the orchestra that is in Vienna while we’re in Miami. One of the violinists in Vienna was talking to someone about a technique, and he was asked “What do you have in your music?” He held it up [to the camera], and it turns out it was something slightly different. This is the stuff musicians do all the time when they’re together. It’s just people developing a comfort zone with this technology.

When I was young, we were lucky to be in a studio close to a master teacher, even before we were old enough to deal with the concepts, to be able to absorb it. It’s exciting to think of the potential to use this to reach those large areas around the country where the students don’t have these opportunities.

To be around and have the influences, even before they can really incorporate them.

There’s a moment in life when you’re ready to absorb something. There also have been times when you’ve absorbed 12 things, and you then realize that all 12 things are the same thing. It’s a recognition, an understanding, of playing an instrument and how music proceeds.

One of the highlights of this coming season is sure to be the premiere of a new John Adams orchestral work. Do you remember when you first met Adams, and what the first work you conducted of his was?

I think it was either Shaker Loops or Short Ride in a Fast Machine, which I commissioned.

Can the Symphony get into the swing of a new Adams piece pretty easily, now that they’ve played a number of them?

We know what to do. We’re also really proud that a lot of his development as a symphony composer is due to works we’ve commissioned.

You are an American composer, and you champion American composers in general. Do you think there are specific musical outlooks that are affected by American roots, even though there may not be that one Major American Symphony?

There are all sorts of outlooks and major symphonic pieces. Americans need have no anxiety about their musical input. The second half of the 20th century shows America’s major influence.

What are you really looking forward to in the season?

John [Adams’] commission. Mason [Bates’] commission. Meredith Monk’s commission. Mahler’s Third; it’s been quite a long time since we’ve done it, and [ours is now] quite a different orchestra. At the end of the season, the Bartók opera, Bluebird’s Castle. There’s so much. There’s probably more, but the PR people won’t like it if I talk out of turn.

And, as a personal question, last year you were on a cooking show with Jacques Pepin. You enjoy cooking, as do a number of other conductors and musicians. Do you think there’s a connection between the two?

Yes, there’s a connection. My perspective is that there is a connection between everything. Music, art, dance, cooking, pottery — these are all connected. There are things to be learned about music from cooking, pottery, gardening, anything.