Mozart’s Don Giovanni is a rapscallion intent upon conquest, but the man who will portray him this June in San Francisco is a family man seeking collaboration. (The new production will complete director Michael Cavanagh’s interpretation of what is sometimes called the Mozart-da Ponte trilogy, in this case setting the story in a dystopian future.)

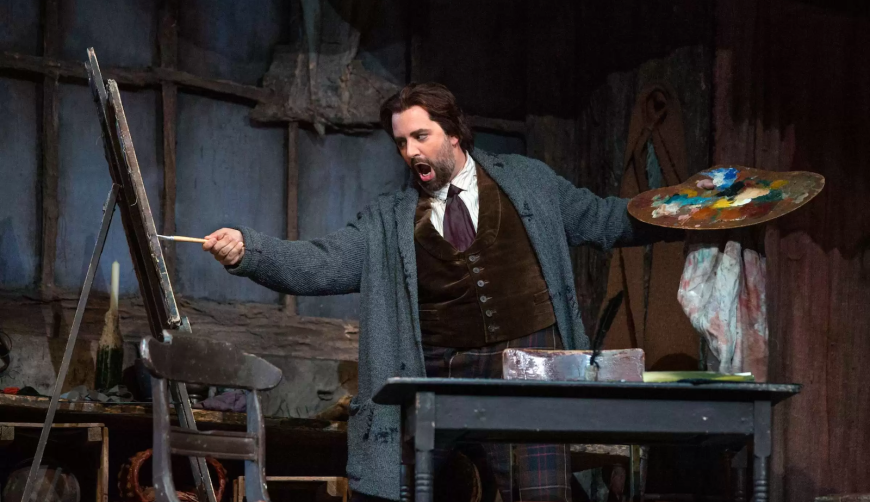

The career of Etienne Dupuis has ascended steadily since the Montréal-born baritone graduated from McGill University and became a member of l’Atelier lyrique de l’Opéra de Montréal. Having sung the mainstay roles for a lyric baritone — Marcello in La bohème, Germont in La traviata, Figaro in Il barbiere di Siviglia, and the Count in Le nozze di Figaro — Dupuis is inching toward heavier roles, with premieres and debuts that have more weight as well.

Recently Dupuis was the Met’s choice for Rodrigue in the company’s first-ever Parisian version of Verdi’s Don Carlos. After San Francisco, which will be a house debut and his first time singing in California, Dupuis will head to Montréal for Il trovatore before returning to Europe for an impressive season with performances in Lyon, Paris, Munich, Vienna, Amsterdam, and Berlin. The eldest of three children, Dupuis did not grow up in a family of musicians, but says that his mother wanted to change that. “When I was in her belly, she would put headphones on her tummy and play LPs, so it could be any kind of music really. And we had a piano in the house and I would go and play on it.”

Dupuis’s wife, Australian soprano Nicole Car, is stepping into San Francisco’s Don Giovanni to sing Elvira, which she recently sang to acclaim in Paris alongside her husband’s Don in another new production, that of director Ivo van Hove. Car and Dupuis first met in 2015 while performing Eugene Onegin at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. The couple have a 5-year-old son, and when not traveling, make their home in Paris. When we spoke, the day after a long rehearsal, Dupuis was relaxed, amiable, and generous with his time in a way that lends credence to the reputation that he does well under pressure.

You sing with a lot of variety, especially with regard to dynamics. Even in something as familiar as the duet in Don Carlo, I hear something new, a nuance. Can you describe how you arrive at that kind of subtle interpretation?

That’s a tough one, because I don’t really focus on that. Every time I listen to a recording of something I’ve done, I also get surprised. [Laughs] In your head you think, I’m going to do that, but you’re not outside of yourself. You can’t hear the result. That’s why it’s important to have people you trust in the audience who can tell you exactly what’s coming out. I truly take it as a compliment though. This is definitely what I like when I listen to a performance as well. My background makes me a musician, but my passion makes me an actor at heart. That connection, when I realize that I can try to create an emotion, or a second layer of meaning, just by doing something musically on a specific word or phrase, that’s the reason I do it.

Singers sometimes have that trained out of them, if teachers overfocus on legato, or being “on the voice” at all times.

I think you’re absolutely right. And sometimes people still try to get it out of me, but it’s just too strong in me. I like to emphasize the fact that it’s also a play, not just music. Right now, we’re doing Mozart, and I love it when conductors or directors say, “You don’t have to sing this, just speak this.” It’s so much more important to convey what’s happening at that very moment. For example, [in Don Giovanni] I’ve just killed the Commendatore, and the first line I speak is, “Leporello, where are you?” It’s in the dark, and the music totally fades out. It would be so weird to say, (sings loudly) “LEPORELLO, DOVE SEI?” It makes no sense. If you just go, [whispers] “Leporello, dove sei?” — it’s so much more interesting.

Is there any difference you can pinpoint between the sensibility of a European house versus an American house, or is the opera world too global at this point?

No, it’s very different. I’ve always thought so. Very young, I participated in a program called IVAI, International Vocal Arts Institute. It was put together by Joan Dornemann and Paul Nadler, who were both working at the Met at the time. They would round up a whole bunch of great teachers and coaches. The program started in Israel and spread to other countries. Right away you were hanging out with all these people from different places. There’s so much to talk about.

You can start with the fact that in America, if you say “I’m an opera singer,” peoples’ first reaction might be, “Oh. But what do you do for a living?” In Europe you say that, and depending on the city or country, not only will you gain a lot of respect, but people will even defer to you or say, “that’s amazing, that’s impressive.” In Vienna, if you say you’re an opera singer you immediately get a better table. Growing up with people going “What are you going to do for a living?,” it forces you to think about the art form in a different way.

Are you at all wary of being perceived as part of a “star couple” or even a “power couple” in the opera world? What’s the difference between being an opera singer and being an opera star?

We don’t think of ourselves as stars at all. Every time we have a conversation about being offered a role, we just talk about it the same way we always have. Is it a good role? Is the period long or short? Is it far from home? Especially now that we have a child; a child definitely helps keep you grounded. We focus on very similar things. I’ve met other opera couples who are so different. But I find that artistic directors who appreciate [Nicole Car] might appreciate me and vice versa because of our similarities onstage. We like to focus on the characters, and the whole show being good. We’re both in it for the whole thing, not for our own personal glory. Even you saying “opera stars” makes me cringe a little bit.

How is the experience different creating a role in a brand-new production, versus doing a classic production, like the Zefferelli Bohème [at the Metropolitan Opera]? I don’t want to call it a museum piece, but how is it different?

I’m going to speak mostly of Germany, Austria, and parts of France. Revival directors, it’s starting to change, but it’s an argument I’ve had many, many times. Not all of them are aware that their job is not only to remount the show exactly as it is. You see the assistants taking notes, and you can kind of tell what kind of revival it’s going to be, if they just care, “Oh, he crossed there instead of there.” Directors don’t care about that. They care if it felt real. Five years down the road, if you try to recreate that, it doesn’t work. And all this has to be worked out in three, four, or five days. It’s kind of ridiculous. So, this is the frame you need to hover in, to do your character. But in that frame, you have to have some freedom, so you can be yourself. Some of my favorite shows have been revivals. You anchor it in a reality, and kind of make it your own, and if you’re allowed to do that very quickly, it’s a great revival.

Some of those museum pieces — [laughs] I love that expression. Sometimes, you look at the names in your costumes and think, “Oh my God.” Or you’ve seen the productions before. You have to remove the dust, the aura of what has come before. Because there’s a sense of “how dare I!” But you have to. You have to dare be an entire person, a hundred percent make it your own character, even though that character has been inhabited by so many people before you.

I always say, people think ego is bad, but there’s a form of ego that we need onstage. Otherwise, the audience sees something which is “inachevé” (French for unfinished). It’s not fully committed. Not fully formed. They see someone wandering and singing, but it doesn’t feel like a character is onstage.

Audiences are smart. They’re like a shark, they can smell blood in the water.

Yes, that’s a great image. If they find a weakness, they zone in on it.

There is a type of singer that has some kind of confidence that breeds confidence in the audience.

That is absolutely true. And I believe there are singers who are better suited for revivals and short rehearsal periods, and others are better suited for long rehearsal periods when you get to create the whole thing and the whole character. And some are good for both, that’s normal.

Don Giovanni is one of those operas that is currently very ripe for reinterpretation, because people have woken up. They don’t want to see a Butterfly with racist clichés, and they don’t want to see Giovanni as a loveable rogue. And historically in productions, you have a broad spectrum from him being extremely charming to him being a total predator.

He’s definitely the latter.

How are you approaching him this time, and also, has San Francisco brought in any kind of intimacy coach? How is that aspect of things being handled?

I don’t think they need to because we’re really not playing that intimacy. There’s something interesting about Don Giovanni: He doesn’t actually get anyone. There have been productions where you see him come out of a room with half naked ladies, but if you just follow what they wrote, he never truly goes anywhere with anybody. There is a time when he and Zerlina could kiss, but it gets interrupted.

We don’t show intimacy because it isn’t necessary. I think what is necessary to show is how that man is disrupting, destroying every life around him carelessly, with no empathy for anyone around him. He walks in on this marriage, of Zerlina and Masetto, and it takes him one second to decide he wants Zerlina, and he never has one thought or consideration for Masetto. That’s just one example. Even when he sees Donna Anna again, after he has killed her father, he doesn’t think, “I’m the man who killed her father.” He speaks to her normally. He’s what I’d call a sociopath. No remorse. No empathy.

Of course, people like that exist in society, and sometimes we isolate them, but not if they are high functioning. Don Giovanni is high functioning. He is capable of imitating what he perceives as humane, but I don’t think of him as remotely humane. [Director] Michael Cavanagh said the word “supernatural”, and I love that idea. It’s like he’s been put there as a test or a challenge for everyone else around him, to at least admit that they’re flawed. We’re all flawed. He focuses everyone’s flaw. Donna Elvira, despite everything she knows, can’t help but throw herself at his feet. That kind of dependency is her flaw. With Leporello, it’s almost the same thing. He needs to be around Don Giovanni to feel better about himself, but he should get out of there. Even Anna is kind of attracted to him, despite everything. Ottavio, whatever you want to think of Ottavio, all the righteousness, the talk, what does he do? Nothing. It’s funny to see how everybody’s flaw comes out as soon as [Don Giovanni] is in the room. He’s a lightning rod. His appearance changes everything. And the moment he is gone, poof! Life can go back to normal.

You’ve said you’ve “nested” in Verdi. I love the use of the verb in that way. Your roles can be classified as “lyric baritone”, or maybe “Kavalierbariton”, but you sing in the biggest houses in the world. Even in Germany, which has so many smaller houses, you sing in the Deutsche Oper. And Munich. Big houses. And Escamillo is coming next year in Paris.

That’s an anomaly.

OK, But what’s coming up? I know your schedule for the next three years, but I mean later, is anything heavier coming up? Would you ever tackle Amfortas [in Richard Wagner’s Parsifal], for example? Are you flirting with anything bigger?

My fun in being an opera singer is to take risks. I call them calculated risks. I want to try new roles. I said “nested in Verdi,” yes. But it’s funny to compare Don Carlos to La Traviata. In Traviata, Germont gets to come in and have a big scene, and disappear. Alfredo too. He comes in, says something important, and then goes out, because it’s all about Traviata. But especially in later Verdi, every character shines. Everyone in Don Carlo has multiple arias, multiple ensembles. Everybody gets to sink their teeth into scenes and convey their character. I love that. I’m moving toward more of these operas.

You mention Amfortas. Why not? These are characters that have something to say. For me, it’s [Jules] Massenet. He wrote so many operas we never perform. There is a version of Adam and Eve, and it’s a soprano and baritone. Why not? We’re doing a concert version of Hérodiade [at Opéra de Lyon and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.] Nicole was listening to it last week and she said “do you have any idea how beautiful this music is?” I do, and I don’t. We don’t really know it until we’re performing it and we’re doing it. We don’t know why we’re focusing so hard on Manon and Werther, and that’s it.

There’s so much beautiful music to discover, even from the composers we already know and love. I love it when people do the “other” Mozarts. Or even the “other” Verdis. We need more Ernanis and Luisa Millers. Massenet is the same. I love this idea that we could start doing a bit more of those, especially grand operas. They were all done by serious people who knew their craft, and they’ve just disappeared. I love “nesting” in that. In characters who have something to say.

The recent Don Carlos in New York had so much intense interest because of being the first time the house had done it in French. What was it like for you to be in such a high-profile production, with that extra pressure?

This is me bragging: When there’s pressure, I get cold. I think over the years people have realized I am quite good under pressure. I am there to do my job and do the best I can, but I don’t care that it’s a milestone for the company. I did eight performances of that, and each one was interesting. I think pressure is good for me. It allows me not to get bored. It’s a gift to be able to do this.