Born and raised in a small town in Wisconsin, soprano Heidi Stober, who was named one of Opera News’s “18 to Watch” in 2018, has been wowing audiences on both sides of the Atlantic since earning degrees from Lawrence University and the New England Conservatory. Winning kudos in an array of roles in works by, among others, Handel, Mozart, Massenet, and Verdi, the singer has also been featured on the concert platform with orchestras that include the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Hong Kong Philharmonic.

Living in Berlin since 2008, when she made her critically acclaimed debut at Deutsche Oper Berlin as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte, Stober bowed at the Metropolitan Opera in the 2011 — 2012 season as Gretel in Hansel and Gretel, a role she is currently singing with San Francisco Opera. The eight-performance run began November 15 and ends December 7. Directed by Antony McDonald in a coproduction with London’s Royal Opera, the work, composed by Engelbert Humperdinck in 1893 and conducted by Richard Strauss at its premiere, is a holiday staple for children and adults alike.

Indeed, Stober has been a regular presence at San Francisco Opera since 2010, having sung numerous roles with the company, including Angelica in Handel’s Orlando in June, which the San Francisco Chronicle’s Joshua Kosman praised as a “... muscular, fearless, and slightly acidic performance.” I spoke with the peripatetic soprano by phone from San Francisco, where she was eager to share her thoughts on a range of topics.

Does the War Memorial Opera House seem like home to you and can you talk about this particular production of Hansel and Gretel?

The San Francisco Opera definitely feels like my home house, certainly on this side of the ocean. They’ve been loyal and I’ve had opportunities to build a wide variety of repertory here. I had never done musicals and in 2014 I did, Showboat and it was one of the most special experiences I’ve had in my career. David Gockley was here then and now with Matthew Shilvock I feel very grateful to have this relationship. I’ve been here once a season and to be able to work with so many different singers, conductors, and everyone from top to bottom [including] the costume people, it feels like coming home to me.

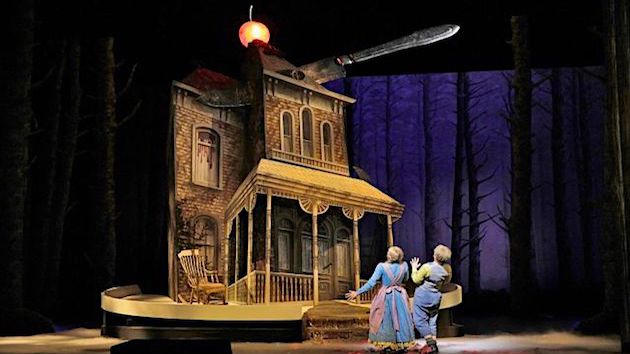

This production is lovely and I hope that people are going to enjoy it. I haven’t worked with Christopher Franklin, before, but he’s a collaborative conductor and the directing team is also great to work with. I’ve performed Gretel in different places with different ideas or takes on [the opera], but there are always new things to bring to the table. Here it’s very German, with a small house in the Alps and I wear a dirndl. It reminds me of a music box I had when I was a girl.

The second scene in the forest is a beautiful pantomime with the Grimm’s fairy tale characters — Snow White and Riding Hood, Rumpelstiltskin and Cinderella — that’s fun. And the witch’s house in this production is both enticing and a bit scary. We also get to eat lots of real food, which is fun as a performer. It’s actually delicious and we’re stuffing our faces like starving kids.

You’ve been in three different productions of Hansel and Gretel, including at the Met, where you stepped in at the last moment. How has being a resident artist with Deutsche Oper Berlin helped prepare you for that — and your career in general?

My training at Deutsche Oper Berlin has been really huge in my development. When you’re an ensemble singer, you’re singing so many different roles — one opera in the morning, another at night — and in one week you could sing in three different operas. A lot of German houses do between 20–30 productions a year. It’s like a Met.

Often, if you’re not doing a new production, you’re doing a remount. My debut in 2008 was Pamina and I had three days of rehearsal. There was no time with the conductor — we met right before the performance to discuss tempos. That trains you well to be ready for everything and anything. At the Met I had three days of rehearsal and saw the conductor for one of those days.

There was no time on stage, no time with the set — and there’s your Met debut. I really give Deutsche Oper a lot of credit, because if I hadn’t experienced that sort of thing, I would have been much more nervous. It was one of the favorite performances of my life and I really enjoyed it. Deutsche Oper taught me what kind of resilience and stamina I have as a singer. You’re doing many different things at once and you don’t have days off between performances.

You actually had to give a performance where you hadn’t rehearsed with the tenor — Roberto Alagna — in Carmen. How is that even possible?

That’s the Deutsche Oper life. They called me up because someone else was supposed to do the performance, so I met him before the performance. It was organic, and we had to go for it onstage together and be open and comfortable with each other. We hadn’t even rehearsed the duet together. I’ve performed with many Don Josés before, but he might have been my favorite — and I mean no disrespect to all the other amazing wonderful Don Josés — but he’s a very generous, open, lovely, easy colleague.

How do you manage to stay vocally healthy with such a demanding schedule?

I try to be quiet during the day, but with different kinds of repertory, a Wagner singer, for example, there’s a difference in the size of the orchestra. It’s not ideal, but our vocal cords do need time to rest in between shows. It’s like you’re running a marathon and you wouldn’t do it two days in a row. You learn what your body is actually capable of.

I understand you twisted your knee on the first night in a new production of Semele for Garsington Opera in England, which brings new meaning to the words, “suffering for one’s art.”

Yes, I did eight performances of Semele with a totally torn ACL. It was the second act and I was onstage and I was in high heels and doing a quick pivot then my foot planted and my knee didn’t follow and I did the whole run of shows with a torn ACL. It wasn’t ideal, but I feel grateful for things from my upbringing that are attributed to different ideas of stamina — that if it’s possible, I would just be pushing through. I also worked hard with a physical therapist during the run of performances — and no, I couldn’t wear heels but ended up being barefoot!

You’re also a fan of new music, having performed in the 2017 world premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon’s The House Without a Christmas Tree at Houston Grand Opera, where your professional training took place and where you’ve performed in more than a dozen operas since 2004.

That was a special piece and it’s a touching story. I do love new music. My first job at Houston Grand Opera was in Daniel Catán’s Salsipuedes, which was the name of a make-believe place. I love new music and I did the [2013] opera, Oscar, about Oscar Wilde at Santa Fe Opera by composer Theodore Morrison. It was specifically about the time before his trial and when he’s sent to prison. It wasn’t about the most successful years of his life, but about his hardest time. It was a cocommission with Opera Philadelphia, and I performed it there [in 2015].

What about your concert work? How do you like singing in front of an orchestra as opposed to working in opera, where the musicians are in the pit?

I love, love, love concert work and love being onstage with the orchestra. This past summer I had the honor of singing at the Grand Teton Music Festival with Donald Runnicles conducting Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Instead of standing as most singers do in front of the orchestra, I was in the middle of the orchestra, with violists on one side of me, bassoonists on the other side.

It was so wonderful to perform that piece in the middle of the orchestra. You really are a part of it together. I love standing in front of them and having that sound envelop you from behind. It was so special for me and the players — it connected us in a different way. I was thrilled he had this idea, because typically for the Mahler No. 4, the singer comes out for the second movement and is waiting for 40 or 50 minutes. It also disrupts the flow of the piece.

[Runnicles] asked me if I would like to be out from the beginning and said, “Let’s try it for the final dress rehearsal and see how that feels.” It absolutely worked and it was exciting. I felt, even though I’m not singing from the first movement on, that I was living it and breathing it before the fourth movement.

How do you feel about the state of opera today — are audiences getting younger, dying off, or just going to see HD filmed productions because the price of an opera ticket can be cost prohibitive?

I think we have work to do, that’s for sure. It’s our job to reach a wider audience and to get young people interested. Everyone I know and friends within the business — it’s important to all of us to find ways to do this. I love singing and my craft as a singer is of the utmost importance to me, but I do believe in this day and age — with Netflix and streaming shows — there are less and less people even going to movie theaters.

I think we have to keep people engaged by also being strong actors. The era of standing and singing, while there is something warranted — the sound of the voice, the words, the artistry of making music and you can be completely still — you don’t have to be running around. There are also many moments that call for that stillness, which can say just as much, because there is acting in stillness, as well.

But I do think everyone I know in the business, including on the presenters’ side, we need people to be engaged and find different ways — discount nights, trying to get young professional groups together, almost like opera clubs. I feel opera is the one art form that brings everything together — the visual arts, instrumentalists, singers, dancers. I know there’s hope, I know there are challenges, but I know we can do it.

Correction: An earlier version of the article misstated that Stober tore her ACL onstage while singing an aria. She was onstage, but it was not her aria.