When she originates the role of an Egyptian queen in John Adams’s new opera Antony and Cleopatra, it will be a full circle moment for Amina Edris. The soprano, whose parents worked in the thriving Luxor tourism industry, spent childhood summers exploring the Temple of Karnak and the Valley of the Kings.

It will also be an artistic homecoming of sorts as the singer returns to San Francisco Opera for the premiere. Edris, an Egyptian native who moved to New Zealand at the age of 10, followed up her time in the Merola Opera Program as an Adler Fellow with the company, and she also took the stage with other local companies, including Opera San José and Opera Parallèle.

The rise of the lyric soprano’s star has been quick. Edris, who is also a San Francisco Conservatory of Music alumna, has already tackled two of her dream roles, Massenet’s Manon and Violetta in La traviata. Mimì in La bohème and Marguerite in Faust are on the horizon.

Edris makes her home in Barcelona with her husband, tenor and Samoan native and (fellow New Zealander) Pene Pati. A recent episode of SF Opera’s video portrait series In Song highlights the soprano’s musical roots. Filmed in Cairo, she sings accompanied on the oud by her uncle, Mamdouh Edris.

As a premiere, the exact nature of the new opera’s music is a closely held secret, but Edris did confirm that there are no arias per se. “John [Adams] said on the very first day of the meet-and-greet that the way he approached the writing of this opera is definitely different from other operas that he has composed. He thought of this particular work as a sung-through drama rather than a traditional opera,” she said, speaking with SFCV via Zoom after a recent rehearsal.

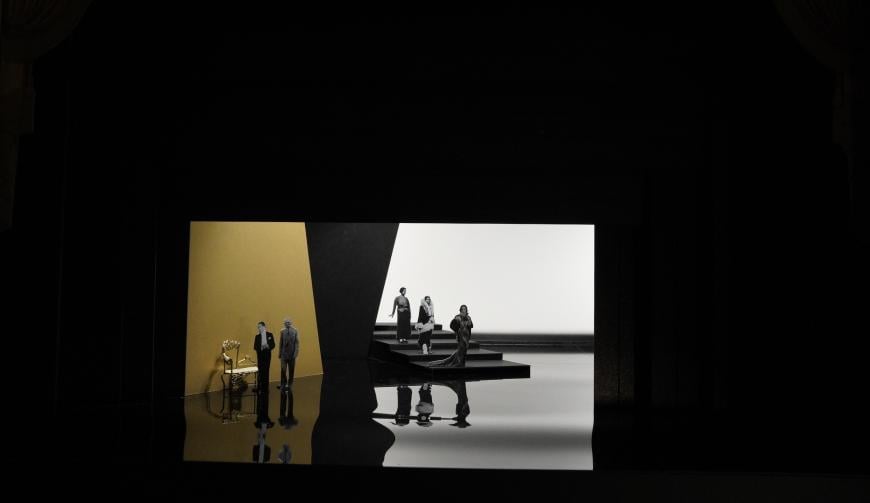

Though she only became attached to the production in May, when soprano Julia Bullock withdrew, Edris seems deeply immersed in the story and character. The production will project the aesthetic of the art deco movie palaces of the 1930s, and a recent publicity photo shows Edris with finger curls à la Claudette Colbert and smoky eye makeup Liz Taylor would approve of.

Would you describe this role as similar in weight and tessiture to Violetta and Manon, or is it very different?

To be quite honest, I have not placed it or tried to compare it to what a role in standard repertoire would be, and I think I probably will keep it that way. Because his [John Adams’s] writing is so specific, it doesn’t make sense to me to try to place it in terms of what would it be classified as, for example within the Fach system. Even more so, because when he wrote this, as with many of his pieces, he is very aware that it is being amplified. I think there is less focus on “Where is the strength in the vocal register? Where will it carry over the orchestra?” … Because let’s be real, if we all tried to sing these roles unamplified, I don’t think any of us would carry.

I know Adams is working with the same sound designer and sound engineer [Mark Grey] that he has worked with on many productions, so he’s got that part figured out.

Gerald [Finley] and John speak very highly of him [Grey], so there’s no worry about that. But I understand your question. I haven’t tried to equate this role. What would this role equal if I compared it to a standard repertoire role? I haven’t gone down that path and I’m not sure I would want to.

I appreciate that. I know that singers don’t give each other advice, really, but Gerald Finley does have the experience of creating an Adams role [in Doctor Atomic]. [Finley is originating the part of Antony with this production.] Have you had any conversations with him about how to approach a new role like this, or what is that artistic relationship like?

Gerald is an absolutely fantastic colleague, and I think we have great chemistry together. We haven’t had a big talk about it. We don’t tend to necessarily go there. But just a few days ago during one of the musical rehearsals, we were talking about different vowel approaches and singing in the extremities of our ranges. John rarely writes in your middle, comfortable range. He’s either very low, or you’re way up, up there. He [Finley] had fantastic advice about manipulating the vowels ever so slightly in your mind, so that when you sing it, the audience will hear what the vowel is. I think because he’s familiar with John’s music, he was able to have some very specific thoughts on that.

I have a very Western view of Cleopatra. What did you learn as a kid in school in Egypt about her? When Americans think of an iconic Egyptian queen, we often think first of Cleopatra.

It’s funny you say that. I would think of Nefertiti, Hatshepsut, Semiramis. I have a slightly bigger list that goes through my mind.

I’m a big fan of Hatshepsut, I just have to say.

My parents were both in the tourism industry, and my mom was a tour guide for French tourists, so she had all this knowledge. And my dad was a co-owner of a jewelry business at the Hilton hotel in Luxor, so we would spend all of our summer holidays at the Mövenpick Hotel because that’s where my dad lived most of the time. It was just a part of my childhood. I don’t think I realized it at the time, but it was very normal for me to join the tour groups she was leading. And I loved exploring in Luxor Temple, the Temple of Karnak, the Temple of Hatshepsut, the Valley of Kings. I was a very lucky child to visit these places every summer and walk in the footsteps of my ancestors.

In terms of what I was taught in school, remember I left Egypt when I was 10 years old, so maybe they taught more about her [Cleopatra] after I left, but I thought of her as one of the longest reigning queens of Egypt, and when you think of her you attach her always to Alexandria, things like that. There was less about her appearance and her sexuality. I think those are more Western views. That was something I never realized she was associated with until I was much older and saw movies, specifically Elizabeth Taylor. I feel like the focus has been primarily on her physical prowess and sexuality.

When I began to dig deep and learn more about her, there’s a very high probability that she was not as beautiful as we have interpreted her in Hollywood or otherwise in the theater. They say they found coins she probably approved where she’s got chubby cheeks and a hooked nose, and she perhaps had a manly figure or dressed in a certain way to intimidate others and to sort of exude more male energy. I found that quite interesting because it goes completely against the stereotypical view, that we’ve come to see her as this seductress who relied on her sexuality to intimidate.

She was very intelligent and very knowledgeable and politically savvy. One can seduce another person with their knowledge and their use of oratorical skills. It doesn’t have to be in a physical form. In saying that, we’re doing John’s interpretation of Shakespeare’s play, so there are things I have to abide by whether or not I believe them to have been true about her because of the way the play is written, and it’s implying a lot of the time that she was manipulating with her body rather than her mind. I have to find a balance and be true to how it is written in terms of the libretto but maybe get creative with the interpretation and the approach.

I have to admit, I see a problem with the Shakespeare, or any of the usual tellings of this story, because there are cliches. For example, that women are passion driven and men are logic driven. And also, there’s a danger of portraying white people (the Romans) as logical and brown people (the Egyptians) as passion driven. I wonder if there have been any discussions with Adams or the director [Elkhanah Pulitzer] of these gender and race issues that the play brings with it.

We have table reads before we look at each new scene or section. At the table reads, we break down each section. I have a book called No Fear Shakespeare, and it’s the play on one side and plain English on the other. Because let’s face it, there are some things you come across where you can kind of make a translation, but there might be something more intricate that you might miss. So that book is extremely helpful, and we have so many helpful resources from everybody on the team. Everybody has translations.

And there is a dramaturg on the production as well.

Yes, and she [Lucia Scheckner] provided great resources that we all have access to. We haven’t necessarily discussed that specific dynamic you are referring to, but throughout, in the choices— I don’t want to say we have made choices because we are still building and changing things, even after we have staged a scene — but the seeds we have planted so far, there have been moments where I have to pause and talk to Elkhanah and ask, “Would she succumb to this? I don’t want to weaken her here.”

It’s important that there’s a display of volatility. Especially in Act 1, there is a scene where she lashes out when she finds out that [Antony] has been married off to Caesar’s sister. John has chosen to include these scenes in the music. It highlights a part of her that is not particularly attractive. But even in those moments, it’s about how I approach the moment before and the reaction after and then the evolution in Act 2.

I always have at the back of my mind that it is important for me to honor who I believe the real person was, even if it goes a little bit against what is set in the music or the text. It is important for her to maintain her dignity because, at the end of the day, when she took her life, it was because she wanted to maintain her dignity and not give the Romans the pleasure of parading her as a prisoner and eventually killing her. I think it’s important to remember that, even at the beginning. No matter the journey, I have this brain working to bring the idea across that she’s a politician. She still has her country’s interest at heart. No matter the inner details of her relationship with Antony, she’s a leader, and that is also in the play.

That’s ultimately the reason that leads to their deaths: because there is a moment of deception. After the Battle of Actium, she has to make a plan. OK, I love him. But I also have to figure out what best serves my people and how I can have power for my children. But she doesn’t tell him, which leads to the moment when they deceive each other and die. That moment is key. It shows this is not a love story. She is making a conscious decision of being a leader before being a woman in a complicated relationship.

It’s not Romeo and Juliet, even though they have that star-crossed mistake at the end.

Right.

One of the interesting things historically is that Cleopatra was perceived with a goddess-like stature. Is that something you consider as a performer? It’s beyond maybe Amneris [in Aida] or any other great princess or queen. It’s almost a next-level, superhuman type of dignity with her.

It’s a very difficult question. I think that’s the next layer. At this point, we are in staging. Obviously, beyond thinking, “What are my next pitches? Where am I in the music?” [laughs] I have to address her as a human first. Then the next layer is to find that godly energy that she believed herself to be. That’s probably my next step in the approach, but I’m not there yet.

In terms of your own voice, I think you can guess I’m going to ask about Adalgisa [in Norma], which you did recently and was such an interesting choice. Can you share a little bit about that and the future?

I’m still staying very much in the line of French and Italian bel canto and Romantic music. I have Musetta and Mimì [in La bohème] in my future and Marguerite in Faust. I’m doing an obscure Massenet piece that is rarely if ever performed called Ariane. I’m singing Ariane. There is a company called Palazzetto Bru Zane. They specialize in finding these rarely performed operas and put together live performances and produce them into albums.

I was just talking about that with the gentleman who sang Don Giovanni here [Etienne Dupuis], and he worked with them.

I think he and Nicole [Car] were involved with some of the projects with Palazzetto. Last year I sang in Robert le diable, which is another gem. Meyerbeer. It is very rarely put on. We did that in Bordeaux, and the album is coming out on Sept. 23. But I’m staying very in line with what I’m doing, but occasionally I’ll take a risk, as with Adalgisa. I think you can take more risks in the European houses. But it’s really not a risk because it was written for an Italian soprano. She was the one Donizetti wrote Norina in Don Pasquale for, which was one of the first roles I did. I did that for Merola.

I didn’t know that about Adalgisa.

Giulia … her last name escapes me. Donizetti and Bellini loved her. Bellini wrote Adalgisa for her and Elvira in I puritani. She was a lyric soprano, but she was quite versatile. When it was suggested to me that they wanted Adalgisa to be sung by a soprano for the festival [Festival d’Aix-en-Provence], the artistic director said, “Do your research, do your digging, but I promise this will be a good fit for you.” So I did a little bit of research.

I think that’s very important because sometimes we assume things about roles just because they have evolved a certain way over the years. We assume they are in a certain Fach. Adalgisa became a mezzo role over time because Norma was always singing the higher vocal line and Adalgisa is always singing the harmony and it was not in the extremities of the mezzo tessitura. I had a wonderful time, and the conductor we worked with, it was his critical edition. They had recorded it several years before with Cecilia Bartoli singing Norma and Sumi Jo singing Adalgisa, and there is a version with Joan Sutherland singing Norma and Montserrat Caballé singing Adalgisa.

And I just remembered her last name, the woman who originated Adalgisa. Grisi. Giulia Grisi.